A Lifetime of Achievement

Mike Lovett

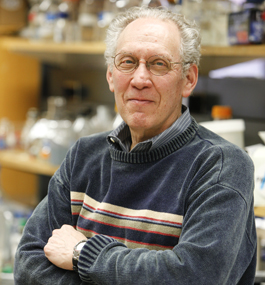

Jim Haber

by Barbara Howard

There’s a career’s worth of meaning in biologist Jim Haber’s latest kudos. Recently awarded the Thomas Hunt Morgan Medal from the Society for Genetics for lifetime contributions in the field of genetics, Haber had never taken a genetics course when he arrived at Brandeis in 1972.

“Somebody said ‘and you will teach genetics,’” Haber recalls. “I really had no business teaching that course, but I did it and I learned by teaching it and by reading books right along with the students.”

Now, 38 years later, Haber is considered by his scientific peers to be among the preeminent biologists studying how breaks in the DNA double helix are repaired and how those breaks affect the cell. The Morgan medal is only the latest in a string of honors. Last year he was elected to the National Academy of Sciences; in 2009 he joined the American Academy of Arts and Sciences; and, in 2005, he became a member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. The Morgan medal recognizes Haber’s groundbreaking research to advance understanding of the origins of cancer as well as his talents as “a superb colleague and teacher.”

The director of the Rosenstiel Basic Medical Sciences Research Center and the Abraham and Etta Goodman Professor of Biology, Haber says the medal is particularly meaningful because Barbara McClintock, a previous Morgan — and Nobel Prize — winner greatly influenced his interest in genetic research.

“Barbara McClintock is truly one of

my heroes,” says Haber, who keeps a photograph of himself with McClintock in his office. “She was the mother of genetic analysis and was one of the first people to study chromosome instability. A lot of my work is focused on those questions.”

Although McClintock studied genes in corn kernels (Haber framed and proudly displays at home several ears she gave him), he took up studying chromosome instability in budding yeast, a simple yet elegant model organism that shares the same chromosome repair pathways as humans.

“Almost all the cells that are cancerous have defects in these repair mechanisms, so we’re trying to understand in detail how cells repair such DNA damage,” says Haber. “In budding yeast we can follow these processes in much more detail than is currently possible in a mammalian model.”

DNA replication is 99.99999 percent accurate, but there are mistakes that result in cell death or cancerous growth. His research has implications for all sorts of cancers.

“It’s a lifetime achievement award,” says Haber, “but I’m not done yet.”