Perspective

The Hollow Promise of Sovereignty

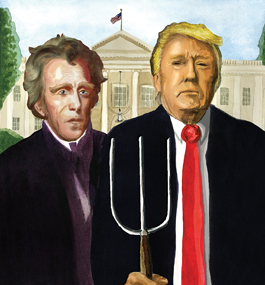

The “populist” tradition embodied by Andrew Jackson and Donald Trump pledges to restore power to the people. In reality, it erodes democracy and unravels societies.

Clare AuBuchon

by J.M. Opal, PhD’04

Again and again, President Andrew Jackson said he was willing to fight tooth and nail for the interests of the common man. “It is to be regretted,” he said in 1832, during his first term in the White House, “that the rich and powerful too often bend the acts of government to their own selfish purposes.”

After Donald Trump won the presidency last year, commentators and historians made the obvious connection: Trump’s brand of populism marked him as Jackson’s natural heir. In his inauguration address, Trump proclaimed the first day of his presidency to be “the day the people became the rulers of this nation again.”

The promises Jackson made and Trump makes don’t involve expanded liberties or greater equality. They center on sovereignty. They assure average Americans they will have the license to swagger; dominate; and ignore the rules of a modern society, except, of course, those rules that elite men like Jackson or Trump depend upon the most.

Therein lies a problem for our democracy.

How do we account for the parallels between the philosophies of these two men, separated by centuries? It’s possible their personalities hold a key. We have seen that Trump is radically insecure. He cannot shrug off criticism; he does not forgive and will not forget any slight.

Jackson, too, was exceptionally sensitive about his “honor.” He once whined that a business partner had treated him “more cruelly […] than ever a Christian was by a Turk.” Over the space of a few months in 1806, he beat a man with a cane, killed another in a duel and threatened anyone who had a problem with any of this.

Americans like him were righteous, Jackson believed. This righteousness justified mass retaliation on non-Americans. “Your impatience is no longer restrained,” Jackson told the soldiers under his military command, just before the War of 1812 began. “The hour of national vengeance is at hand.”

He was referring to vengeance not just on Great Britain, but on all the federal and international rules that threatened to hamper his and his peers’ ventures. Why should the U.S. government respect native lands in a way that blocked merchants from new markets? Why should international law stop Americans from speculating in foreign lands or pursuing runaway slaves?

Even after the war officially ended in 1815, Jackson used his troops to destroy native villages and kill fugitive blacks. And he promised to “avenge the blood” of the American people killed during the war by taking on milquetoast politicians and international norms.

In a similar vein, Trump has long called for extreme retribution on nonwhite criminals, including the five men of color who were convicted and later cleared of a brutal rape in Central Park in 1989. Decades later, he took control of the Republican Party by promising to deport Mexican immigrants, torture Muslim terrorists and bully other countries.

The appeal of men like Jackson and Trump is their rage against anything that checks their prodigious desire for wealth, power and fame. They are not interested in presenting a better version of themselves — or the nation — a trait that makes them seem genuine, no matter how often they exaggerate (like Jackson) or lie (like Trump). Above all, they invite “the people” to retaliate against those who dare limit their sovereignty.

Where does that sense of sovereignty come from? Why do some Americans feel entitled to mistreat others while pursuing their own happiness? One answer is the long history of slavery in America. Another, more pertinent answer is the U.S. Constitution, which gives “We, the People” the power to make fundamental law. The people — not the Crown, not God — ultimately rule. All Americans know this.

page 2 of 2

Less well-known is how that same document blocks ordinary people from real power, especially the power to rein in business tycoons and the wealthy. Article I, Section 10 of the Constitution secures what conservatives still call “the sanctity of contracts.”

In Jackson’s time, if a man was unable to repay a debt, the Constitution ensured his creditor could repossess his clothes, his livestock and even his home. Jackson got his start as a lawyer who represented creditors. He became a judge who opposed repeated efforts by state governments to halt auctions and foreclosures during hard times. For him, social norms existed to secure investments and contracts. Otherwise, they were a nuisance — a check, however modest, on his sovereignty.

As president, Jackson rejected government plans to build more roads and canals, and to establish a national university. He let large speculators gobble up the land he had seized from natives, and freed wildcat bankers from the regulatory efforts of the Second Bank of the United States. He believed people should be able to buy all the land and make all the deals they wanted, as long as the courts were there to take everything back when the economic bubble burst.

Trump follows the same pattern. He champions “the people” not as a democratic society, but as selfish and commercial individuals, bound by their contempt for others. He attacks “bad” trade deals, not because he opposes unfettered capitalism, but because other countries try to protect their citizens from it. Both authoritarian and laissez-faire, his administration targets labor and environmental regulations, and slashes domestic spending. It glorifies oil and mining companies while ignoring the competing interests of their workers. Trump’s brand of populism hacks away at American society while leaving core rules governing wealth and property unmentioned and untouched.

The tragedy of this political tradition, then, is that it deprives the people of the very sovereignty they seek. It makes them more fearsome to their enemies but less able to help one another. It opens new commercial frontiers while dismantling the U.S. economy. It makes America more of a nation beyond the law and less of a nation bound by it. It invites people to see the poor, the marginal and the caring as “losers” rather than as fellow citizens.

And it will go on enfeebling democracy and undoing progress until its opponents learn to assert sovereignty within society, to insist that each citizen is equally American, equally honorable and equally protected from people like Donald Trump.

J.M. Opal, associate professor of history at McGill University, is the author of “Avenging the People: Andrew Jackson, the Rule of Law and the American Nation” (Oxford University Press, 2017).