'We Cannot Leave Science to the Experts'

A Q&A with Paula Apsell '69, the award-winning "Nova" exec who wants to turn TV viewers into citizen scientists

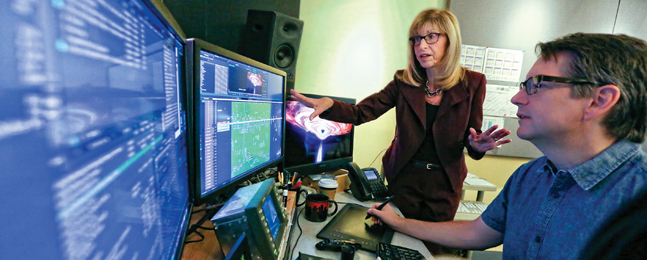

Mike Lovett

STORIED CAREER: Paula Apsell '69 at the WGBH studios in Brighton, Massachusetts.

by Lawrence Goodman

Ever wonder what it would be like to peer inside Einstein’s mind? Or what animals are really trying to tell us? What it would be like to fall into a black hole?

Paula Apsell ’69 has spent many years pondering these mysteries and countless others as senior executive producer of the PBS series “Nova,” the gold standard of science journalism on television and online.

Hired by “Nova” founder Michael Ambrosino in 1975, two years after the series debuted (and a chorus of critics predicted its quick demise), Apsell took over as executive producer in 1985. Today, “Nova,” produced at flagship station WGBH, is seen by more than 40 million viewers in the U.S. annually and is shown in more than 100 other countries. The winner of more than 25 Emmy awards,“Nova” is the most-watched, most-respected science series on American television.

Apsell has not only perfected the science documentary format for TV, she’s proved equally adept at forging a path in the digital age. “Nova” was among the first PBS series to reach a million followers on Facebook. In addition to its website, it produces two popular web platforms — Nova Labs for teens and Nova Education for teachers — and YouTube channels such as “What the Physics?!” and “Gross Science.” “Nova” podcasts are currently in development.

Her influence on science journalism was recognized in October by a Lifetime Achievement Emmy, one of television’s highest honors. In her acceptance speech, she said, “We live in a time of great misunderstanding of science, a time when science is under attack, when facts are fungible, when truth isn’t always truth. Frightening as this is, it’s tempting to think of it as something new, but sadly it’s not. History is full of anti-science movements.”

And so, she said, the need for informed debate is more urgent than ever: “We have no choice. We cannot leave science to the experts. We — all of us — have to become citizen scientists.”

Apsell’s own scientific exploration began at Brandeis. Though not far geographically from Marblehead, Massachusetts, where she grew up, the university was a world apart intellectually. In a piece she wrote in 1998 for “Brandeis University: A People’s History,” she described her arrival on campus: “Coming from a small and very traditional high school, I was overawed and intimidated by the high-level intellectual community of which I had become, nominally at least, a part. But gradually I was drawn into it, almost despite myself. The first class that really excited me was a physical science course taught by [physics professor] Dr. [Hugh] Pendleton. I was fascinated by his lectures on the Copernican Revolution and the power of scientific thinking to change society.”

Mike Lovett

IN THE EDITING ROOM: "We agonize over graphics and animation because they are critically important but very expensive."

page 2 of 3

In a work-study job at Brandeis — scanning bubble-chamber photos, images of subatomic particles making their way through a superheated transparent liquid — she met her future husband, Sheldon Apsell, PhD’70, then a graduate student in the high-energy physics labs of Sandy Wolf and Lawrence Kirsch. Sheldon went on to invent the LoJack stolen-vehicle recovery system and found MicroLogic, an electronic-product development company. The couple, who live in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts, have two grown daughters, one a physician, the other a television news producer.

Here, Apsell talks about her storied career, the state of science journalism and the backlash against science in American political life.

How did Brandeis spur your interest in science?

I was a psychology major, so it was certainly nothing organized or programmed. It was more that the atmosphere at Brandeis stressed the importance of science and how interesting it is. Also, there was an interdisciplinary approach to the sciences that showed how science is related to policy, humanism and human values.

How did you get started in TV?

I started out as a log typist, which is the lowest of the lowest of the low — you type the time of every single piece of video and audio that goes on-air. It’s completely automated now, which is merciful because it’s a horrible job. But it gave me a great opportunity to walk around the station — the logs had to be handed out every day — and I got to know everybody.

In 1974, Michael Ambrosino started “Nova.” Science programming on TV was a completely new idea. Michael had gone to England to learn how the BBC did it, and he brought back a lot of ex-BBC producers to, essentially, teach us. And as soon as “Nova” went on the air, it was incredibly popular. I joined “Nova” in its second season as a production assistant.

This very quirky, lucky thing led to my becoming a producer on “Nova.” We were making a program on smallpox eradication. We were supposed to go to Bangladesh to film what were thought to be the last two cases of smallpox in the world, but there was a coup d’etat in the country and we couldn’t get there. After the program became more of an archival film, it was passed down to me. Epidemiologists at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the World Health Organization had done an amazing thing, which had never been done before or since: eliminate a disease from the face of the Earth. Today, they would be besieged by press, but, back then, nobody talked to them, except me. These were fantastic interviews, and I really got the bug.

I eventually left “Nova” to work for two years at WCVB-TV in Boston for Dr. Timothy Johnson as a senior producer for medical programs. I was lucky enough to get what is now called a Knight Science Journalism Fellowship at MIT in 1983. That was a fabulous year, during which I studied a lot of science policy and the history of science. Then I was offered the job of executive producer at “Nova.” I’ve been there ever since.

Courtesy PBS Pressroom

BUILDING SCIENTIFIC LITERACY: With a replica of the mummy known as Otzi, who lived in the Alps between 3400 and 3100 BCE.

page 3 of 3

There weren’t many women in broadcasting back then.

In some ways, I was too young, naive and laser-focused on learning my craft to let that bother me. The difficulties faced by women and people of color actually trouble me a lot more now. I’m a proud feminist, and I worry that a lot of the progress that’s been made is being eroded.

You place a high value on featuring female scientists and scientists of color.

We want our shows to reflect the diversity and experience of the American people. We want young people who might become inspired to go into science or engineering to see someone on our program who looks like them.

How do you choose topics for “Nova”?

We look for a natural story line — a mission to be accomplished, an obstacle to be overcome, a problem to be solved. We develop scientists as characters, with their own passions and drives, who reflect the excitement of science. And we go into the details of science so our viewers can understand them. It’s one thing to make shows for entertainment. That’s hard.

It’s another thing to make good video for education. That’s hard, too. We have to combine education and entertainment. I always say we’re in the education business, we’re in the entertainment business, but, most of all, we’re in the inspiration business. If you watch our programs and say, “Wow, that’s a great adventure. I want to emulate that in some way,” we’ve succeeded.

The show’s graphics are exceptional in their clarity and design. Can you talk about your creative process?

We agonize over graphics and animation because they are critically important but very expensive. Generally, we ask our animators early in the process to create “style frames” that we can use while we’re cutting. We don’t do the real graphics until much later. We’re very lucky technology has given us so many new ways to graphically express scientific concepts.

How long does it take to produce a show?

For the past several years, we’ve done a number of quick turnaround films, where we follow an event such as Hurricane Sandy; the meteorite over Chelyabinsk, in Siberia; or the solar eclipse over America in 2017. And then there are multi-part productions such as “Making North America” and “The Fabric of the Cosmos,” which can take up to two years.

Who is your typical viewer?

A curious person of any age who enjoys learning about our world and ourselves, and likes a good story with great pictures.

How have you managed to stay competitive with the other heavy hitters in science TV?

Both National Geographic and Discovery do science films on occasion, but “Nova” is on the air and online with great science and engineering stories week after week, all year long. Over many decades, we’ve built a loyal viewership and a great reputation, which helps our fan base grow.

Science journalism often falls into the trap of hyping findings or results. How have you managed to avoid that?

I hate the word “breakthrough” because, in general, it’s an inaccurate description of what goes on in science. Science is fundamentally incremental. Reporters who don’t realize that are making a mistake.

Why do you think regard for the sciences is at an all-time low?

The fact that science is under attack makes me very sad and frightened for our country. If you look at the latest Pew [Research Center] study, you see that an enormously large percentage of Americans still respect science. In fact, scientists are the second most-respected people after the military, according to Pew. But in our political life, attacking science can be a popular thing to do, certainly in areas like climate change and evolution.

Why do so many people continue to deny climate change despite the overwhelming scientific evidence?

Those of us who accept that climate change is happening have to understand that changing from fossil fuels to renewables or taking steps to reduce car emissions is very disruptive, and will affect many people’s lives. And we have to care about those people, too. It’s not OK to say, “OK, you’ve always made your living as a coal miner, you made a decent living — well, now you’re going to be unemployed.” We have to understand that all these things have human impact.

Is there a way to shift public perception about climate change?

The important question to get people to answer is “Do you want the lives of your children and grandchildren to be more difficult than yours due to unstable climate conditions?” And if their answer is no, they want to leave the world a better place, then they understand we have to do something about the problem.

What’s next for “Nova”?

I suppose this goes back to my Brandeis education, but we are really looking at making more programs about the intersection of science and society, or science and social justice. We have a program this season on opioid addiction, which looks at treatments that use medications, and the impact of getting over the idea that addiction is a moral failing and starting to see it as a brain disorder. Though these shows won’t dominate the series, there will be more of them than in the past.