Panic, presented by Welles

Thomas Doherty discusses the 75th anniversary of the radio broadcast of 'The War of the Worlds'

It was Halloween Eve 1938, a typical Sunday night for Orson Welles and his Mercury Players, who were doing what they did best: entertaining.

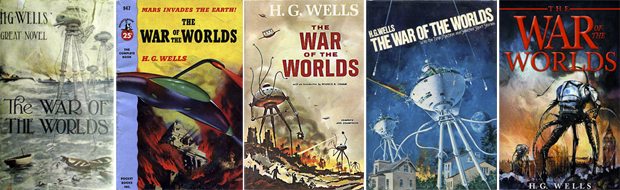

At 8 p.m., the sounds of their weekly CBS radio show, “The Mercury Theatre on the Air,” filled living rooms throughout the East Coast with their adaptation of H.G. Wells’ popular 1898 science-fiction novel, “The War of the Worlds” — set in Grover’s Mill, N.J., instead of England.

What happened next was anything but typical.

The story of Martians invading New Jersey captured the imagination and inflamed the fears of thousands of listeners, who mistook the inventive broadcast for reality. People began phoning the police, packing belongings and fleeing the area. Reports of mass hysteria dominated the following day’s headlines.

Seventy-five years later, many still wonder how the hysteria happened and whether it could happen again. Professor of American studies Thomas Doherty offers some thoughts about this vivid event in U.S. broadcast history.

Can you briefly describe the “War of the Worlds” broadcast?

On the night of Oct. 30, 1938, Orson Welles’ famous Mercury Players performed H.G. Wells’ — no relation — “War of the Worlds,” creating this famous panic along the East Coast of the United States. It’s become this animating incident that demonstrates the effects mass communication can have on people.

How is the Orson Welles script different from the H.G. Wells novel?

Well, the story takes place in New Jersey! Otherwise, it remains pretty faithful to the Wells novel. The basic trajectory is that Grover’s Mill is invaded by Martians who can zap us. In the end, what kills them is bacteria they can’t fight off.

Why were so many listeners fooled?

You need to consider everything in the context of the threat of German invasion. People had heard nothing but menacing news of invasion all October. That’s what was in the newspapers.

The other thing that’s so interesting is how the broadcast duplicated, technologically and aesthetically, what the coverage of an invasion would have actually sounded like. Live radio broadcasts from Europe by Edward R. Murrow had just launched that March — live, crackly, static-filled radio broadcasts from abroad. The Mercury Theatre broadcast duplicated that, along with the short-wave whoosh and woo. Also, the actors playing reporters intentionally stumbled over their words and made glitches an authentic broadcast would have had.

Those are the two contexts that made people persuadable.

Was that Welles’ intention?

This is a subject of great speculation. My sense is that Orson wanted to fool some people but had no idea that he would get so many people and get them so well, that it would be so authentic.

He was involved in a lot of experimental work in theater, and of course he would later go on to film. The filmic version of this is the opening of “Citizen Kane,” the first mockumentary. If you came into a showing of “Citizen Kane” late, it would seem as if it were an episode of “March of Time.” It’s so powerful because it is a tone-perfect imitation. With just a little twist, it could be the real thing.

There’s newsreel footage of a Welles interview the day after the “War of the Worlds” broadcast, and he does not look smug and satisfied. He looks authentically startled and afraid of what could be some of the legal consequences.

In the radio broadcast, they repeatedly say this is the Mercury Players presenting Orson Welles. But there’s been a lot of discussion about people perhaps tuning in in the middle of the broadcast and in their panic they don’t hear the disclaimers.

Radio never did anything like this so authentically again. CBS put in place some pretty rigorous standards.

Were there other clues that the broadcast wasn’t real, if folks missed the introduction and the disclaimers?

You’d recognize Orson Welles’ voice if you were a regular listener.

But another thing he put in was the breaking-news bulletin, which had just been developed. Music would be playing, and they’d interrupt. All those devices — he was just so devastatingly clever. He really wanted to get people, a little.

Were the reports of the hysteria exaggerated?

The New Jersey police blotter still exists, and it’s very long. It just goes on forever. They were getting a lot of phone calls from people.

Could this happen now in the U.S.?

Not unless it was an intentional deception. We’re just too media-smart, and the reason we’re so smart is Orson Welles. We have very finely tuned media sensibilities. If someone set out at 6 o’clock to deceive Americans, you’d turn to the next channel and learn it’s not true. Welles taught us to be a little more savvy.

The “War of the Worlds” deception happened at just the perfect time, when radio had achieved 100 percent penetration in America. It was a perfect combination of world history, technology and Welles’ artistic brilliance.

Why is this incident so important?

This is one of the first real moments where you can’t deny the power of the media — if the media can actually persuade people that there are Martians invading, and they’re fleeing their houses. It’s similar to what Nazi Germany did with mass media, how the Nazis consciously used mass media to serve their ends.

What impact did “The War of the Worlds” have on Welles’ career?

It probably, in the end, gave him a boost. But his peers hated him because he was a young genius. Nobody likes a 23-year-old genius, especially in Hollywood.

But we don’t remember him only for that. In anyone else’s obituary, this broadcast would be the lead item and that would be it. In Welles’ case, it’s historically important, but we remember him for work like “Citizen Kane.”

What place does the broadcast have in history?

It’s among the top five mass-communications events in history — along with the Kennedy assassination, Pearl Harbor, 9/11 and the Lindbergh baby kidnapping.

What we don’t have now, the difference between the broadcast world then and the digital world now, is everyone listening to something at the same time. If I want to watch an episode of “Breaking Bad,” I don’t have to be home at 9 o’clock on Sunday night. I can DVR it or TiVo it.

People use the “War of the Worlds” broadcast as a metaphor for the power of radio from 1929 to the onset of TV in the 1940s and ’50s. This connecting wave, this hive mind in America — it was the first time we were electronically connected. It was this new experience, where people instantaneously heard the same communications.

Categories: Humanities and Social Sciences