Witches in the archives

Brandeis houses historic works of demonology and witchcraft

Robert D. Farber University Archives & Special Collections Department, Brandeis University

Robert D. Farber University Archives & Special Collections Department, Brandeis UniversityIllustrations by George Cruikshank from Sir Walter Scott's "Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft"

Deep in the cool, dry basement of Goldfarb Library, faces of death mingle with witches, demons and the devil. Welcome to the Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections.

The Archives house hundreds of volumes and precious artifacts, including the death masks of the Italian American anarchists Ferdinando Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti.

Among those treasures are a number of history’s most famous works about demonology and witchcraft, exposing humankind’s deep fascination with the supernatural, and the tragic realities behind such beliefs.

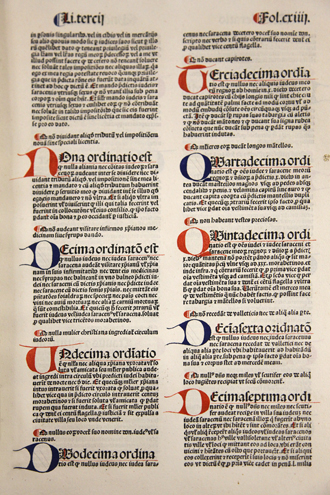

“Fortalitium fidei” by Alphonso de Espina, 1485

|

| De Espina's "Fortress of Faith" |

Alphonso de Espina, best known as one of the harbingers of the Spanish Inquisition, published the first printed book to contain references to witchcraft. The five-part work, translated as “The Fortress of Faith,” explores what de Espina, a powerful Spanish Franciscan friar, deemed the greatest threats to Christianity: heretics, Jews, Muslims and the Devil. De Espina classifies demons into 10 categories including goblins, incubi and succubi, and demons that specifically target old women. De Espina writes about assemblies of women in southern France who were burnt — the earliest printed reference to the burning of accused witches. “Fortalitium fidei” is often credited as a precursor to Western demonology and witchcraft lore, but that isn’t the scariest part of this work. “The Fortress of Faith” is also credited with fueling anti-Islamism and anti-Semitism and reigniting blood libel accusations across Spain. De Espina, who some scholars believe to be a Christian convert, called for the expulsion of all Jews and Muslims from Spain. Less than a decade later, the Inquisition was established, during which scholars estimate hundreds of thousands of people were killed.

Gift of Lewis K. and Elizabeth Land

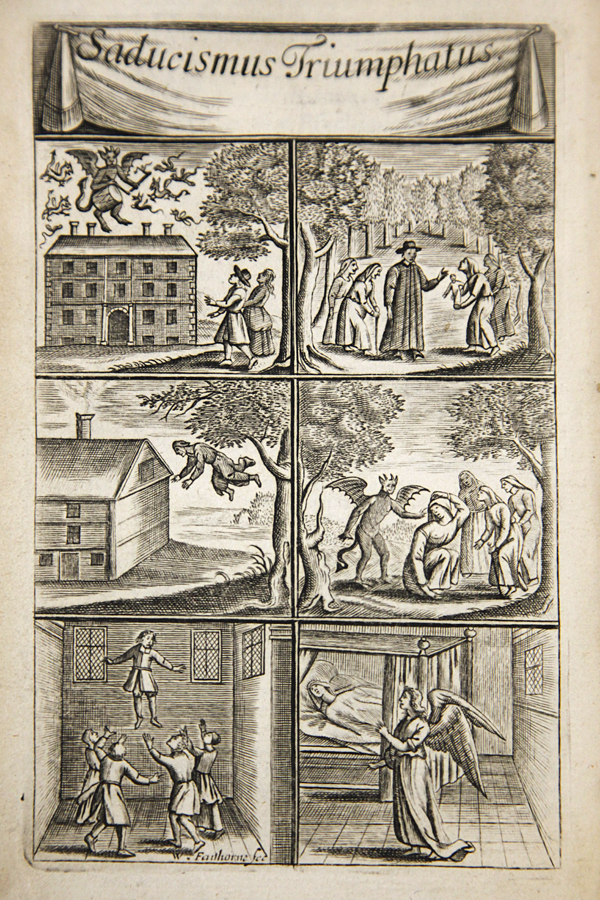

“Sadducismus triumphatus: or, A Full and Plain Evidence Concerning Witches and Apparitions,” by Joseph Glanvil, 1726

|

| Glanvil's "Sadducismus triumphatus" |

Joseph Glanvil (1636-1680) was an English clergyman and philosopher. In the latter half of the 17th century, the cognoscenti were struggling to reconcile new approaches to science and religious thought. As a member of the Royal Society of London, the oldest scientific body in the world, Glanvil was a strong supporter of both empirical research and the supernatural. “Sadducismus trimphatus” calls on logic and first-hand accounts to decry skepticism of the spiritual realm. Glanvil personally investigated a popular poltergeist, known as the Drummer of Tedworth, and collected other stories of witchcraft from around the country. For Glanvil, and many others at the time, belief in the supernatural was an argument against atheism. His empirical approach to the supernatural influenced other thinkers of the time, including Cotton Mather, whose writings on witchcraft fueled some of the hysteria leading to the Salem Witch Trials.

Part of the Perry Miller Collection on the Colonial Religious Experience in America

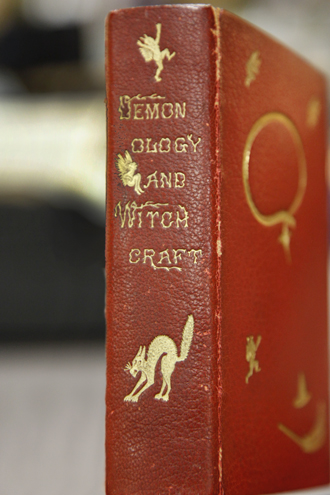

“Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft,” by Sir Walter Scott, 1830

|

| Scott's "Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft" |

Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832), author of “Ivanhoe” and “Rob Roy,” began writing “Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft” at the end of his life, shortly after his first stroke. By the late 19th century, the zealotry of witch hunts had faded, though pockets of superstition remained. Although long interested in the supernatural, Scott was profoundly skeptical of it, and these letters express sympathy and outrage for the men and women of the previous century accused of witchcraft and executed. In one letter, Scott retells the story of the Salem Witch Trials, saying that the colonists were “deluded and oppressed by a strange contagious terror.”

George Cruikshank, who illustrated many of Charles Dickens’ novels, illustrated many of the scenes Scott describes in his letters.

Gift of Mr. and Mrs Samuel H. Maslon

Categories: Humanities and Social Sciences, Research