The sturgeon, the fish that changed history

In a talk, environmental historian Nancy Langston detailed the amazing role the fish has played in the development of the planet and the growth of human society.

Her talk on March 13, part of this year’s Mandel Lectures in the Humanities, traced the history of the animal in North America from the Triassic period 250 million years ago to present-day conservation efforts in the Great Lakes region.

Along the way, she showed how deeply intertwined the whisker-snouted fish is with the history of the planet and the development of human society.

Nancy Langston

Not bad for a fish mostly known for producing the eggs eaten as caviar.

“They have some serious history,” said Langston, the Distinguished Professor of Environmental History at Michigan Technological University. “This is not just human history. This is like, really serious history.”

Sturgeon evolved long before the dinosaurs. Their direct ancestors survived the Great Permian Extinction that killed nine out of every 10 species and soon became the dominant, big fish in every major river system in North America and Eurasia.

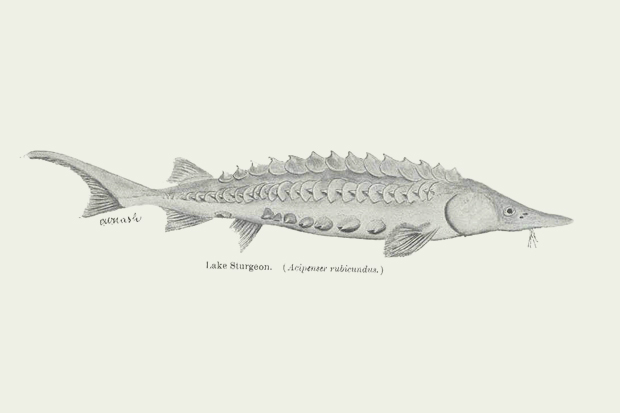

Roughly 150 million years ago, they settled into their current size, shape

They have sucker-like mouths with fleshy lips — “little Dyson vacuum cleaners that have evolved to go sucking up the crustaceans and mollusks and crabs, and then they just kind of swallow them,” Langston said.

Lake sturgeon migrate back to their birthplace to spawn. The Indigenous peoples who inhabited the Great Lakes region moved around with the fish, which were a major food source.

According to Langston, sturgeon were so plentiful that the Potawatomi and Ojibwe tribes’ legends “tell of rivers so full of sturgeon that a person could walk across the water on the backs of the fish.”

The Ojibwe, who now

Initially, the European settlers who pushed westward in the 1800s traded with the Native Americans for dried sturgeon to eat. Very soon though, the commercial fishing industry arrived and targeted herring and lake trout instead.

Since sturgeon ripped through commercial fishing nets, fishermen soon viewed the sturgeon as pests. “And so commercial fishermen just slaughtered them,” Langston said.

Meanwhile, the whites pushed the Native American tribes off their land, enabling further habitat destruction.

When steamships came along, fisherman piled sturgeon on the shores of rivers and lakes and dried them, burning them for logs for ship fuel.

In the 1880s, entrepreneurs realized they could sell sturgeon roe as caviar. Soon, the Great Lakes produced much of the world’s caviar.

In the early 20th century, newly built paper mills dumped pollutants into the water where sturgeon swam. The myriad dams erected to provide power for the mills obstructed sturgeon migration.

Sturgeon

“Any one of these things and sturgeon could be resilient against them, but when they all happen one after another, both the sturgeon and Indigenous peoples found themselves with a problem,” Langston said.

The last part of Langston’s talk charted the conservation efforts in the last 20 years to restore the Great Lakes’ sturgeon population. The effort, she said, was led primarily by the tribes in the region. They “began to go to the states and say, ‘Hey, we want a voice in this. We don't want to just manage the fish. We want to restore the fish.’”

According to Langston, the Indigenous peoples saw saving the sturgeon as inextricably bound up with strengthening their own community. They recognized that “healthy human communities are tied to healthy nonhuman communities,” she said.

Today, sturgeon are making a slow, but steady comeback. This is why Langston likens them to zombies — “because they’re never quite dead. They keep returning,” she said.

Efforts to save the sturgeon are now part of a collaboration between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. “So this is as much a story about restoring sturgeon to the watershed,” Langston said, as “trying to heal these moments between Anglos and Indigenous peoples, trying to find some shared future in a shared watershed with a fish.”

Langston’s talk and three others she delivered as part of the Mandel Lectures in the Humanities will be the basis of a forthcoming book from Brandeis University Press.

Categories: Humanities and Social Sciences, Research