The scholarly journey of Hortense Spillers

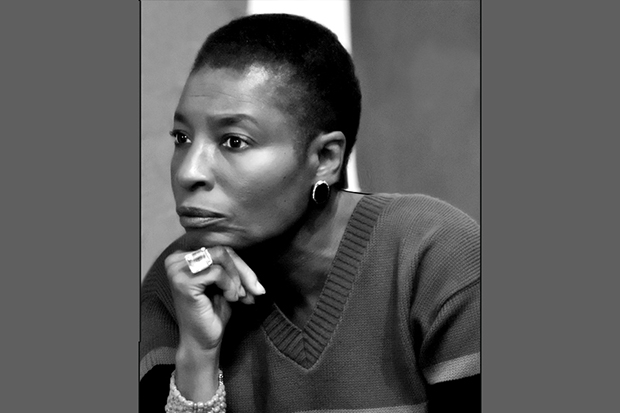

Hortense J. Spillers, PhD'74, professor of English at Vanderbilt University, reflects on her academic journey as she receives the Alumni Achievement Award

Hortense J. Spillers, PhD'74

Hortense J. Spillers PhD'74 is an American literary critic, black feminist scholar and the Gertrude Conaway Vanderbilt Professor of English at Vanderbilt University, and on Feb. 9 will receive Brandeis' Alumni Achievement Award during the African and African American studies 50th Anniversary events on Feb. 8 and 9. But before she began accumulating awards as a leader in her field, she was a newly-minted PhD candidate driving a Buick Skylark from Memphis to Brandeis in the tumultuous summer of 1968. In answer to questions posed by Faith Lois Smith, associate professor of African and African American Studies and English, Spillers discussed her evolution as a scholar and what black feminist theory can teach us in the present moment.

You completed your doctorate at Brandeis in 1974 – how did your studies here influence your development as a scholar? Did your focus change appreciably from when you arrived to when you defended your thesis?

Spillers: I think it is fair to say that when I arrived at Brandeis late summer, 1968, I was in for a powerful awakening, if not a rude one, although the latter is also not inappropriate to the way I read the situation at the time. I was coming from my parents’ in Memphis and following two years, on my very first professional gig, as a young green instructor of composition at what was at the time Kentucky State College in Frankfort, the state capital. KSC was then an [Historically Black College or University]-United Negro College Fund institution of considerable standing and had been for a number of years; our campus was hit hard by MLK’s murder that spring, followed by Robert Kennedy’s, so that ’68, to say the least, was brimming over with confusion, heartache and heart break. There was nowhere to rest internally because it seemed that revolution in the United States was imminent. Chaos reigned in and out, it seemed! So here I come, driving my first car, a Buick Skylark, from Memphis, Tennessee, fresh out the driveway of the house I’d been born in, to Waltham, Mass, trailing my homey, Rev. “Skeet” Sanders, driving his car, enroute, I think, to Yale Divinity School at the time! Well, you …my plans between the time of entering Brandeis and leaving it not only changed! They did somersaults and boomerangs!can imagine how that works: two young black southerners, both going north to school. I’ve forgotten now how I found out that Rev. Sanders (whose beloved Aunt Delora Thompson had taught me in the third grade) and I were going in the same general direction, but I learned a helluva lot about North American geography that year! I’d never spent very much time at all outside the southern United States so that to my deepest mind Massachusetts and Connecticut might as well have been next door to each other! Well...hours later as I drove and drove beyond the cut-off point where I was separating off from my companion driver, I came to the realization that “New England” had not been named in vain! I had come a long way from the Mississippi Delta and a tad more than a hop, skip, and a jump from Connecticut! And then the learning started in earnest!

When I entered Brandeis, I knew I wanted to study literature, but I thought I was headed for the English Romantics — or I should say, William Blake, an early Romantic, but none of that even remotely happened. Exactly how things unfolded that first crucial year remains to my mind a massive bright obscurity, but the road I consequently took very much had to do with what we didn’t know at the time was a veritable intellectual movement that would shift the curricula of the human sciences toward the dimensions of diversity that characterize the study of Higher Education in the U.S today, and that is to say, the Black Studies movement. Never officially called that, it occurred to me years later that’s exactly what we were having — a movement among black students on predominantly white campuses in the country to put on the ground — right now! — a curricular object based on the life-worlds of Africans in the global African Diaspora. Well, that dramatic and abrupt and radical emergence of difference changed every imaginable thing! I forgot all about the English Romantics and turned my wide-eyed, big-eared attention to the sermon rhetoric of black preachers and quite specifically that of Martin Luther King that had actually changed the country, or had most certainly been a critical factor in changing it. To make a long story short, my plans between the time of entering Brandeis and leaving it not only changed! They did somersaults and boomerangs!

Your analyses of gender and diaspora use psychoanalytical and other canonical discourses; "All the Things You Could Be by Now if Sigmund Freud's Wife Was Your Mother: Psychoanalysis and Race." is one example. What might this tell us about the canon, the university, and the production of knowledge?

My use of certain canonical forms and figures in my work is for me proof positive of what some thinkers, Ralph Ellison was among them, have in mind when they speak of the “mysteries” attendant on American culture; Ellison’s “Little Man At Cheehaw Station” powerfully defines this notion as an elaborate conceptual thematic and a serviceable metaphorical/heuristic device: Ellison bases his argument on a fabulistic invention, the “little man at Chehaw Station.” The latter was the name of a train stop many years ago when students, among other passengers, traveling to school at Tuskegee Institute got off at the site, enroute to campus. Chehaw, then, was a terminus through which passengers traveled in and out of the state of Alabama; I think I vaguely remember having heard the name Chehaw as a child because my elder sibling, my sister, went off to college at…the producers of knowledge turn out to be, at least in theory, anybody, as the canon is ripe for employment in the service of one’s own needs and desires; from that angle, it belongs to human invention and not a particular group’s. Tuskegee, my first trauma, when I was three years old, and it may be that I first heard the name then. Anyway, as Ellison tells the story, one of the big furnaces at the station sprouted a “little man” who was, so to speak, the keeper of the flame; this seems to me a kind of folkloric invention that grows out of the collective creative imagination as a way to explain certain aspects of human existence. The “little man” seems to belong to a repertoire of otherworldly figures that come to us out of the invisible world, but keep us company with their wisdom; with their mystery. Among the resources that make the little man timeless is his knowledge of the culture and the details that constitute it. In that regard, the little man knows things that no one would believe he knows, and that’s why he is most useful to Ellison insofar as he stands in for knowledge in unexpected places; in short, because American culture in its fluidity and porousness, as Ellison reads it, is not confined to a particular class or station in life, any audience of Americans, at any given time, will have knowledgeable people in it because knowledge goes where it is least expected.

What this is saying, in effect, is that the United States produces a climate that wants to assign place and status and knowledge accordingly, but that’s not what happens. In that way, the canon, the university, knowledge production should all, by convention and according to who has and who has not, who is ordained to speak and who is not, all belong to the advantaged. But the beauty of the cultural order, as Ellison is reading it, is that there is no law or necessity or mandate that confines or constricts those eventualities to a specified class of persons; they are open to the one who knows, who finds out, who has the greatest curiosity, the deepest feeling. If that is so, then the producers of knowledge turn out to be, at least in theory, anybody, as the canon is ripe for employment in the service of one’s own needs and desires; from that angle, it belongs to human invention and not a particular group’s. Freud, for instance, made significant contributions to our understanding of the mental theatre and the operations of consciousness and the unconscious. But the European provenance of Freud’s ideas, say, does not foreclose the usefulness of the latter as a window onto the psychic formations of other cultural and historical subjects, though Freudianism will have to be revised and corrected for those radical swerves and divergences of “situation specificity.” As an investigator, I simply assume that I am an inventor, a bricoleur, and that the entire world is my tool box.

What do you think our present political moment can learn from black feminism(s)?

What black feminisms might teach the current social order begins with concernful care for other human beings; not that black women do this, or anything else, perfectly, but it seems to me that they are aware of it as a good goal, as an ideal toward which to strive. Black feminism also seeks a degree of critical independence in relationship to the social order so that its posture is the critical posture. But I need to make a distinction between black women, black women as the subject of feminism, and black feminism as a critical disposition; all three of these distinctions might well overlap and show relationship to each other, but they also define distinct positionalities that we tend to occlude; for example, not all black women are feminists, or the subjects of feminism, not even black feminism, and insisting onWe are also being summoned to look at another truth that stares us in the face every day, and that is the extent to which women in power do not always look and behave very differently from the males who preceded them in power. the difference allows us to capture nuance, and enough nuance spells the difference between night and day, hot and cold, etc. I can, for example, think of a couple of black women, public figures and empowered, by virtue of their proximity to powerful white Republican males, who would not be in agreement, I suspect, with any aspects of black feminism, and least of all, black feminism’s positions on race, class, gender, sexuality, etc. There are more black women with whom we have very little in common than we are comfortable thinking about so that a subject of black feminism might at times — and this is rather shocking, I admit! — find greater common cause on some issue with other women than with those women whom she regards as members of her own community. One of the tasks of black feminism in the years to come is to acknowledge these very uncomfortable truths and not anticipated differences and explain how they work. We are also being summoned to look at another truth that stares us in the face every day, and that is the extent to which women in power do not always look and behave very differently from the males who preceded them in power. I am of the opinion that women who reach certain levels of management and privilege often forget something along the way, and that is, the necessity to forge a different image of power; in that regard, male leadership is not exemplary, and I see no need to repeat it or imitate it; in short, we don’t need women who really want to be either like men or men themselves, whatever we decide that is, and as hard as it is to say these days, I think we know it when we see it.

I should like to think that black feminisms, as a repertoire of concepts, practices, and alignments, is progressive in outlook and dedicated to the view that sustainable life systems must be available to everyone; it also stands up for the survival of this planet, which pits it against the kleptocratic darkness that now engulfs us. If we’re going to reach a different place — and it is difficult these days to be hopeful, I would acknowledge — then black feminist ideas and ideals might be one of the lights leading us there.

Categories: Alumni, Humanities and Social Sciences