Louis Dembitz Brandeis Collection

Description by Winston Bowman, Archives and Special Collections Assistant and PhD candidate in history

The Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department’s Louis Dembitz Brandeis Collection boasts approximately 101 linear feet of material by and about Justice Brandeis. The collection houses a wealth of primary-source material, most produced by Brandeis and his immediate family. In addition to providing rich resources for those interested in Justice Brandeis’ personal and public lives, this collection offers an array of material on American legal history, the Progressive and Zionist movements, the U.S. Supreme Court and the foundation and early years of Brandeis University.

The Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department’s Louis Dembitz Brandeis Collection boasts approximately 101 linear feet of material by and about Justice Brandeis. The collection houses a wealth of primary-source material, most produced by Brandeis and his immediate family. In addition to providing rich resources for those interested in Justice Brandeis’ personal and public lives, this collection offers an array of material on American legal history, the Progressive and Zionist movements, the U.S. Supreme Court and the foundation and early years of Brandeis University.

The collection is dominated by correspondence, providing unique insights into Brandeis’ relationships with his wife, Alice and children, Susan and Elizabeth. A committed correspondent, Brandeis wrote several letters on most days. These letters were frequently brief and pragmatic, but often also contained interesting observations on contemporary events. Brandeis’ family is also well represented in the collection. Their letters help to provide a fuller picture of Brandeis’ personal life. In addition to the letters she wrote to Brandeis and her family, the Alice Brandeis files contain a small but interesting set of documents on the Brandeis household, as well as a large set of condolence letters she received in 1941 upon her husband’s death. The letters of Susan Brandeis and her husband, Jacob Gilbert, offer insight into their own activities in American Zionism and the creation of Brandeis University. The files on Elizabeth Brandeis and her husband, Paul Rauschenbusch, are small, but also provide important glimpses of the history of the Brandeis family.

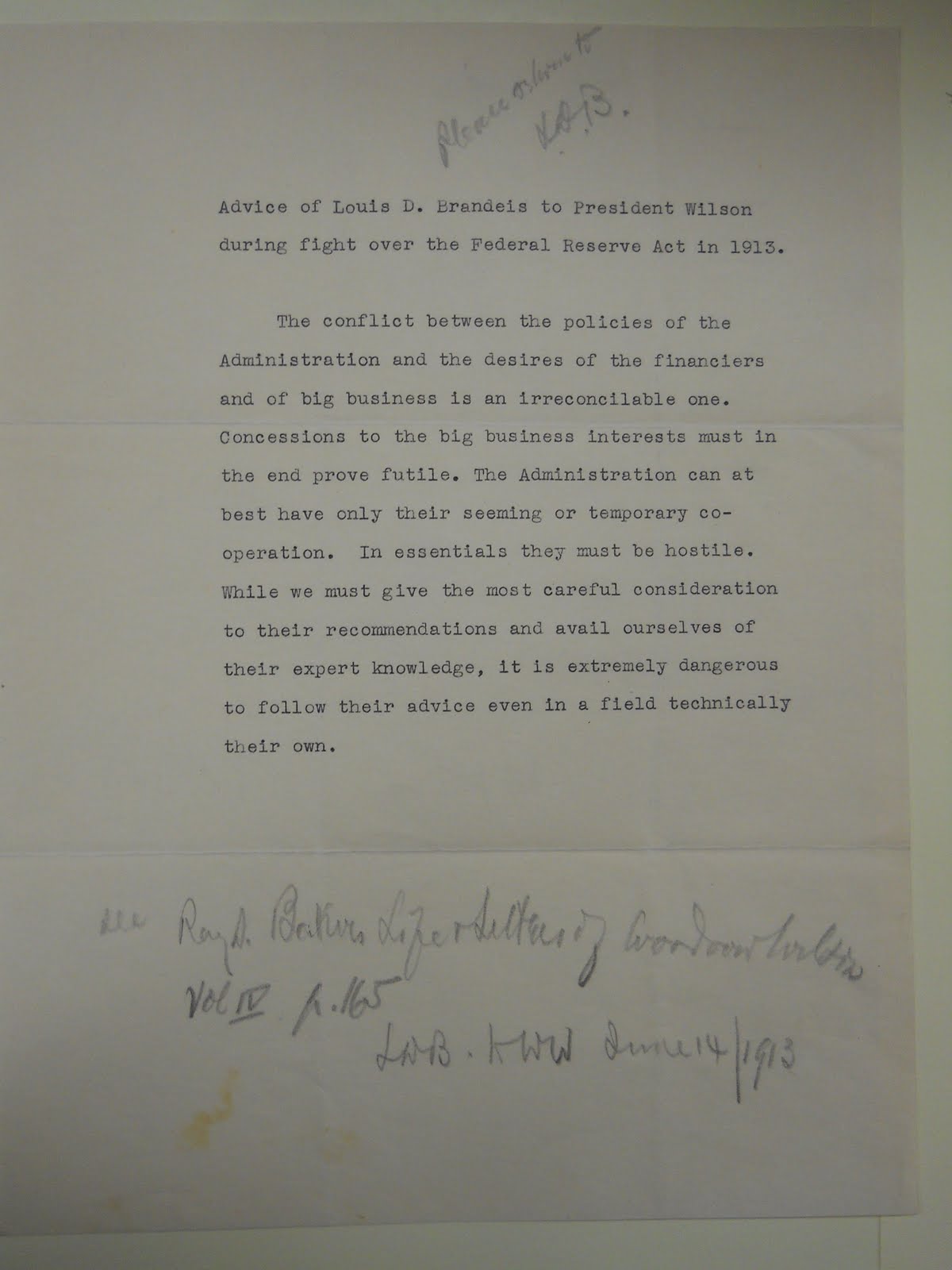

The collection also provides a wealth of sources for historians interested in the development of Brandeis’ political, legal and intellectual views. These sources include early-edition copies of many of Brandeis’ most famous publications and speeches, as well as notes and suggestions to President Wilson and other friends and colleagues, and information relating to a number of Brandeis’ appearances before Congressional committees. The collection also features several more intimate speeches and interviews about Zionism.

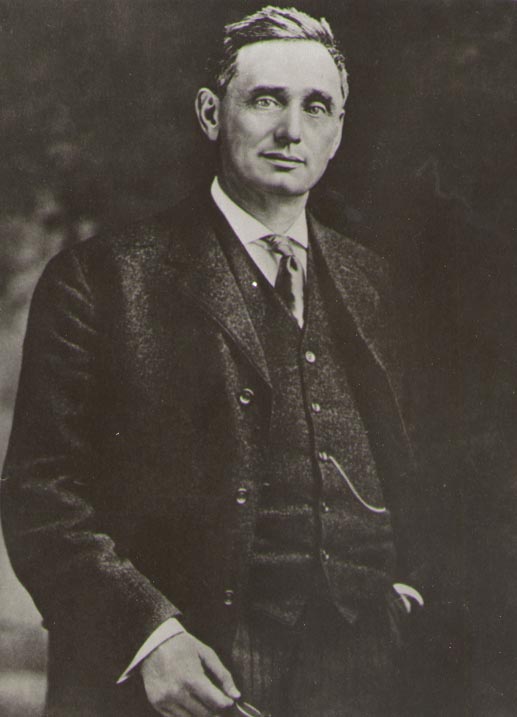

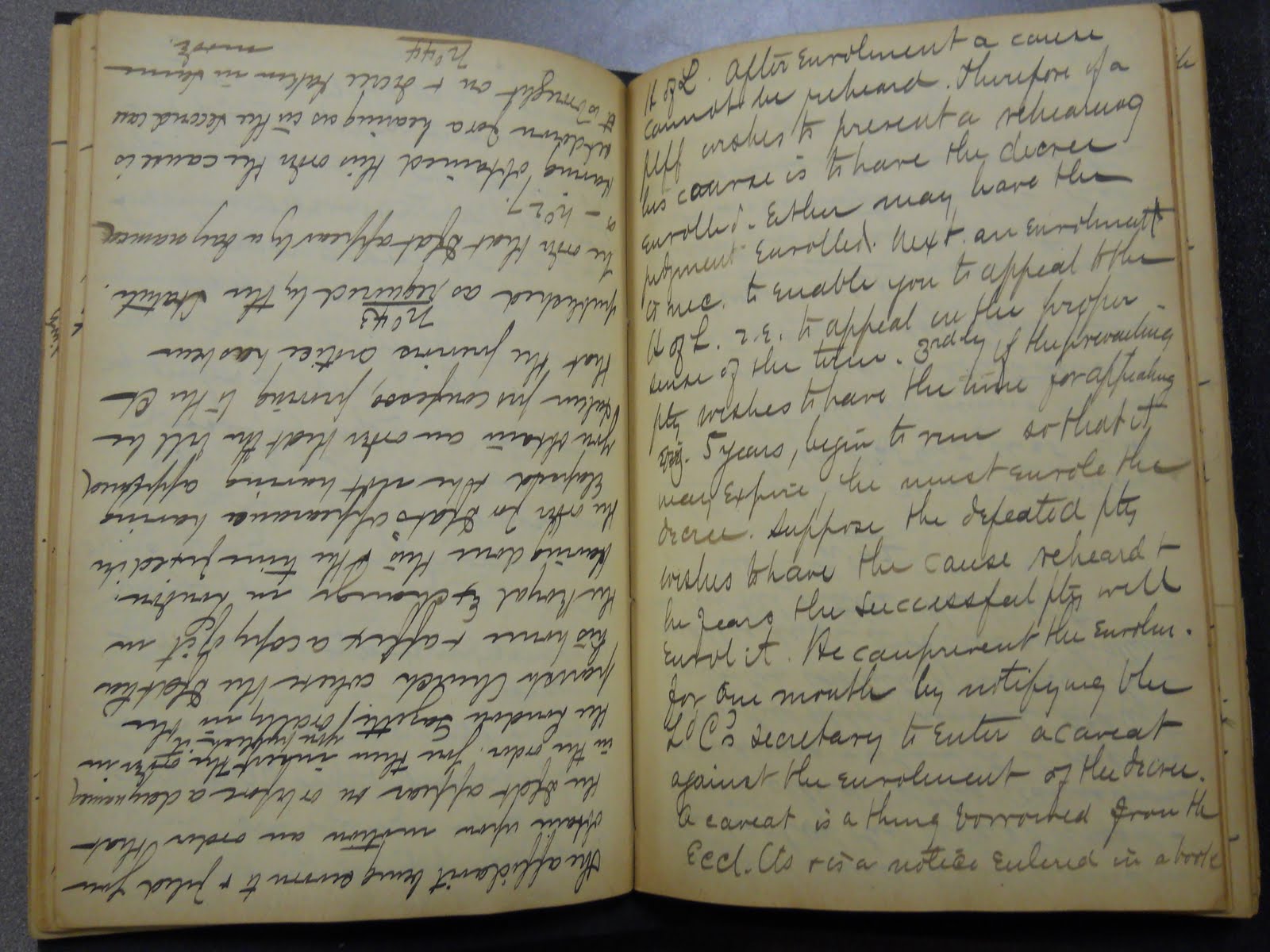

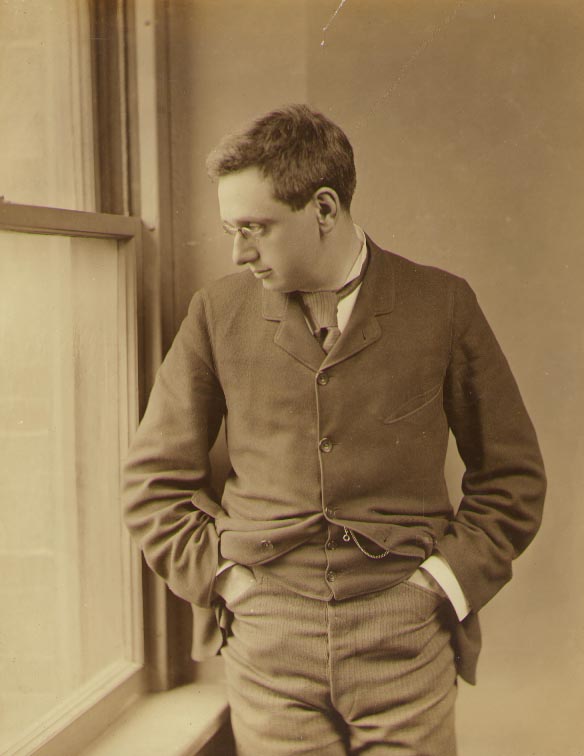

One of the most influential legal minds of the 20th century, Brandeis was born in Louisville, Kentucky, on November 13, 1856. His parents, Adolph and Frederika, were Bohemian Jews from Prague. The Brandeises immigrated to America following the wave of revolutions across Europe in 1848. Adolph proved a successful businessman in the new world, and the young Brandeis grew up in relative comfort. After a three-year trip to Europe with his family, Brandeis returned to America in 1875 and enrolled at Harvard Law School at the age of 19. His decision to embark on a legal career was influenced by his uncle, Louisville attorney Lewis Dembitz, whom Brandeis would later honor by adopting his name. Brandeis excelled academically, graduating from Harvard in 1877 as the law school’s valedictorian.[1] The collection holds several notebooks from his time at Harvard that illustrate the development of his legal thinking there.

One of the most influential legal minds of the 20th century, Brandeis was born in Louisville, Kentucky, on November 13, 1856. His parents, Adolph and Frederika, were Bohemian Jews from Prague. The Brandeises immigrated to America following the wave of revolutions across Europe in 1848. Adolph proved a successful businessman in the new world, and the young Brandeis grew up in relative comfort. After a three-year trip to Europe with his family, Brandeis returned to America in 1875 and enrolled at Harvard Law School at the age of 19. His decision to embark on a legal career was influenced by his uncle, Louisville attorney Lewis Dembitz, whom Brandeis would later honor by adopting his name. Brandeis excelled academically, graduating from Harvard in 1877 as the law school’s valedictorian.[1] The collection holds several notebooks from his time at Harvard that illustrate the development of his legal thinking there.

After graduation, Brandeis spent a brief stint practicing law in St. Louis, Missouri, before retuning to Boston in 1879, founding the Brandeis-Warren law firm with Harvard classmate Samuel Warren. The firm became a major success (indeed, it remains a leading Boston firm under the banner Nutter McClennan and Fish, LLP), and Brandeis’ own reputation as a litigator grew. Over time, Brandeis began to devote more of his professional attention to supporting progressive social and economic causes, earning the moniker “the people’s attorney.” The collection holds records from the firm relating to Brandeis’ business.

Form followed function in Brandeis’ litigation practice, as he introduced the use of extensive social science information as an integral part of appellate briefs. This innovative technique reflected Brandeis’ progressive faith in the scientific study and control of social forces. Using information compiled by his sister-in-law Josephine Goldmark, Brandeis first employed the “Brandeis brief” in Muller v. Oregon (1908),[2] a decision upholding hours regulations for female workers based in part on Brandeis’ evidence that long workweeks had particularly deleterious effects on women.

Form followed function in Brandeis’ litigation practice, as he introduced the use of extensive social science information as an integral part of appellate briefs. This innovative technique reflected Brandeis’ progressive faith in the scientific study and control of social forces. Using information compiled by his sister-in-law Josephine Goldmark, Brandeis first employed the “Brandeis brief” in Muller v. Oregon (1908),[2] a decision upholding hours regulations for female workers based in part on Brandeis’ evidence that long workweeks had particularly deleterious effects on women.

Brandeis also applied progressive ideologies in counseling businesses. Following the example of industrial efficiency experts like Frederick Winslow Taylor, Brandeis insisted on "scientific management." This approach encouraged managers to measure every aspect of their businesses with a view to better allocating resources and increasing efficiency. In so doing, Brandeis aimed to increase profits for companies while decreasing costs for consumers.

During much of his legal career, Brandeis maintained the attention to the academic study of law that marked him out as a star in law school. He taught courses on evidence and business law at Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology respectively. In December, 1890, he and Warren published “The Right to Privacy” in the fledgling Harvard Law Review.[3] Observing that photography and other recent innovations had diminished the level of protection accorded individuals’ private lives, Brandeis and Warren claimed the law should recognize and police the boundary between the public and private. A similar devotion to “the right to be let alone” later led Brandeis to write his famous dissent in Olmstead v. United States (1922),[4] arguing that warrantless government wiretaps violated the U.S. Constitution’s Fourth and Fifth Amendments. This dissent eventually became a touchstone of modern privacy jurisprudence, influencing everything from investigative procedure to abortion and contraception.[5]

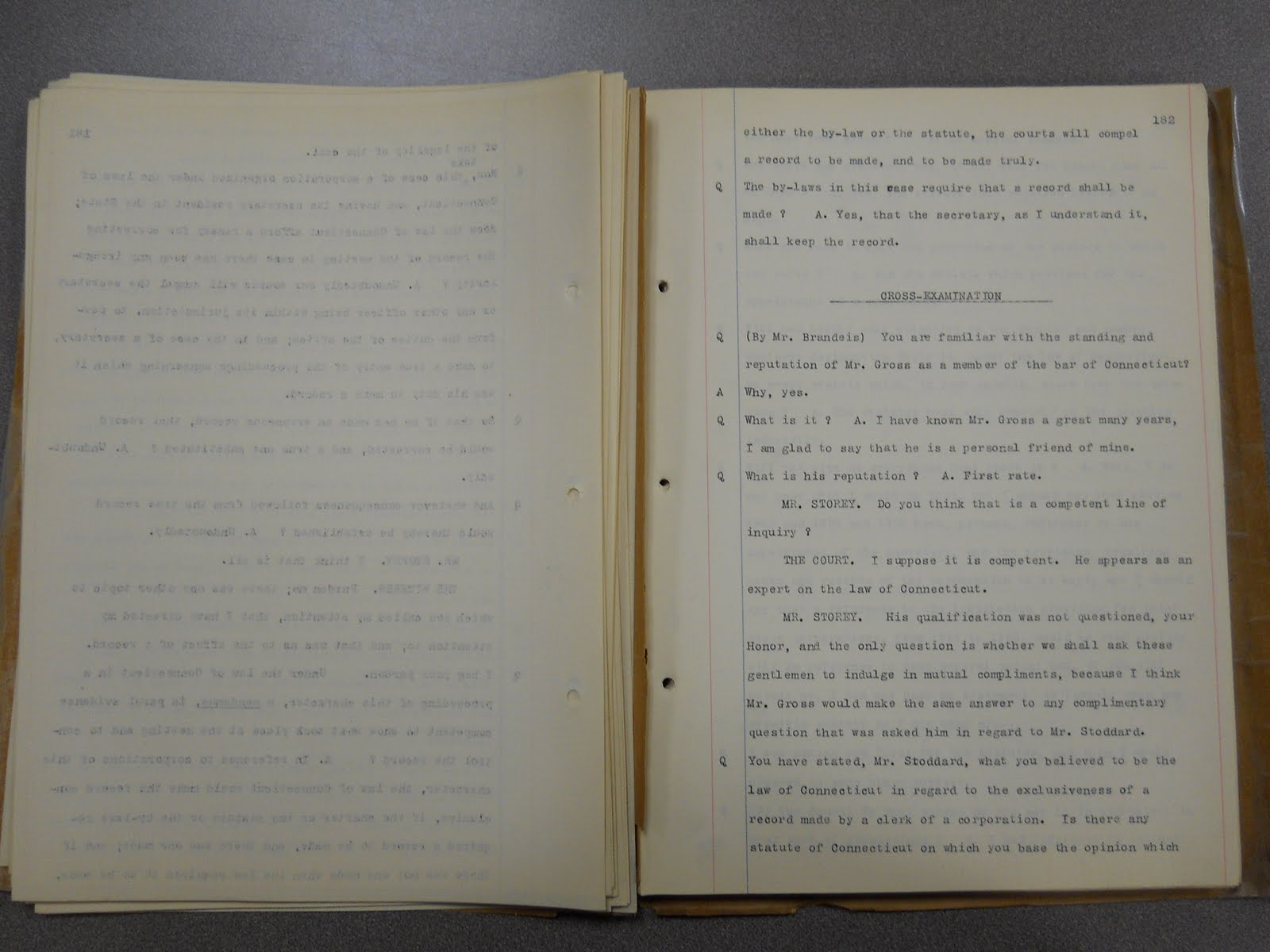

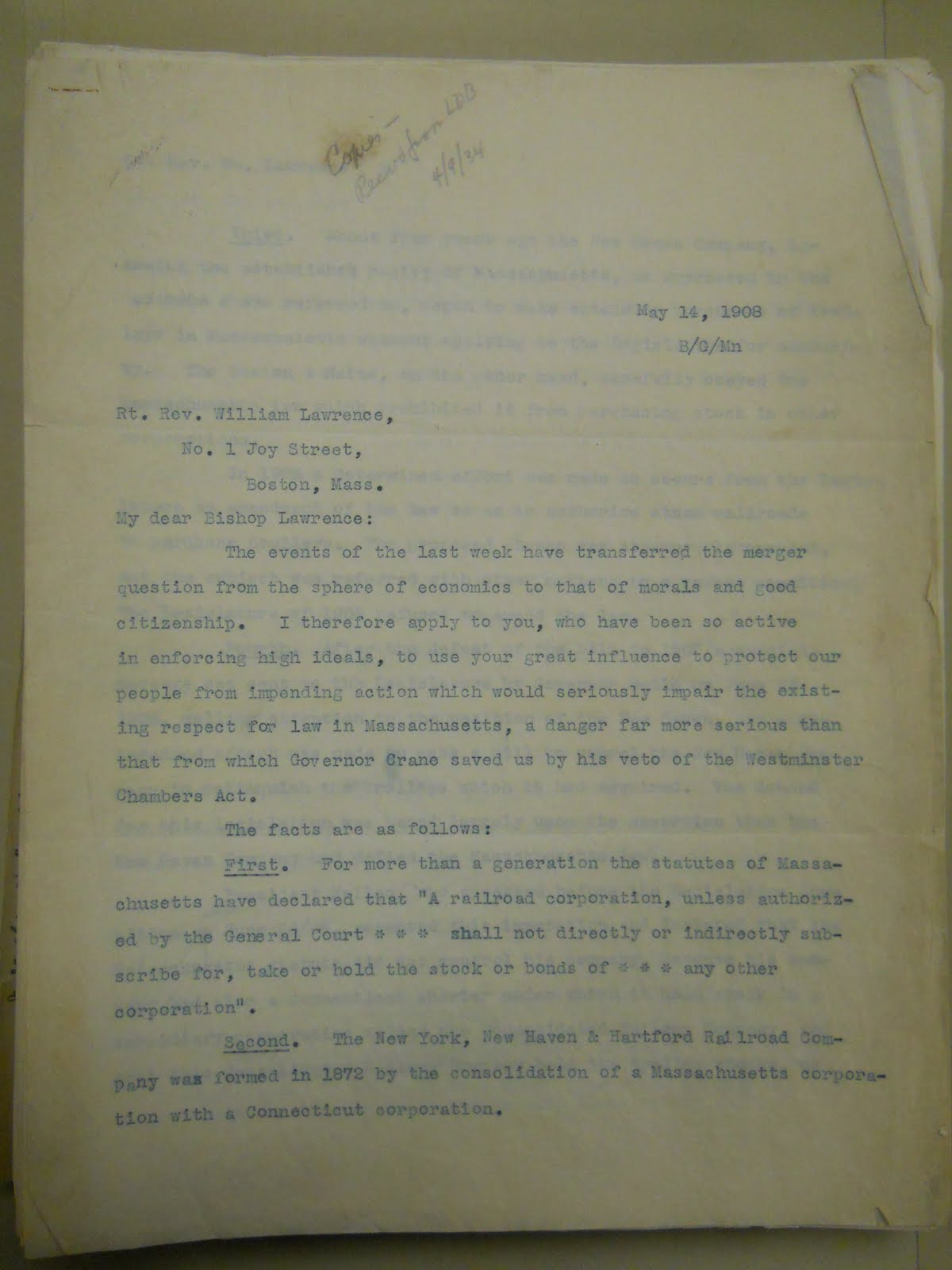

An increasingly sought-after litigator, Brandeis attracted national attention when he successfully fought J.P. Morgan’s attempted monopolistic merger of New England railroad companies between 1905 and 1914. The collection boasts hundreds of pages of material (much of it handwritten) on Brandeis’ crusade against the New England railroad merger. Brandeis’ increasing fame, and his strong support for Democrat Woodrow Wilson’s presidential candidacy in 1912, led Brandeis to Washington, where he helped to shape Wilson’s “New Freedom” agenda.

An increasingly sought-after litigator, Brandeis attracted national attention when he successfully fought J.P. Morgan’s attempted monopolistic merger of New England railroad companies between 1905 and 1914. The collection boasts hundreds of pages of material (much of it handwritten) on Brandeis’ crusade against the New England railroad merger. Brandeis’ increasing fame, and his strong support for Democrat Woodrow Wilson’s presidential candidacy in 1912, led Brandeis to Washington, where he helped to shape Wilson’s “New Freedom” agenda.

This service was rewarded in 1916 when Wilson appointed Brandeis to the U.S. Supreme Court. The selection proved politically divisive, with Brandeis’ Jewish background and social activism working against him. Brandeis’ confirmation hearings were testy and infused with a palpable anti-Semitism in some quarters. Nevertheless, he was confirmed by a Senate vote of 47-22, albeit with minimal Republican support.[6]

Once he arrived on the Court, Brandeis carved out a unique place in America’s judicial canon.[7] Along with his friend Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., Brandeis crafted several notable dissenting opinions designed to protect the First Amendment free speech rights of political dissidents.[8] Brandeis wrote several important opinions developing an increasingly sophisticated set of procedures governing the federal court system. In the most famous of these opinions, Erie Railroad Co. v. Tompkins (1938),[9] Brandeis fundamentally altered the balance of judicial federalism in America by reversing nearly a century of precedent in holding that federal courts could not create their own judge-made rules and had, instead, to defer to state court judgments on such matters. This opinion reflected his antipathy for centralized power and big government.[10]

Once he arrived on the Court, Brandeis carved out a unique place in America’s judicial canon.[7] Along with his friend Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., Brandeis crafted several notable dissenting opinions designed to protect the First Amendment free speech rights of political dissidents.[8] Brandeis wrote several important opinions developing an increasingly sophisticated set of procedures governing the federal court system. In the most famous of these opinions, Erie Railroad Co. v. Tompkins (1938),[9] Brandeis fundamentally altered the balance of judicial federalism in America by reversing nearly a century of precedent in holding that federal courts could not create their own judge-made rules and had, instead, to defer to state court judgments on such matters. This opinion reflected his antipathy for centralized power and big government.[10]

However, Brandeis’ record on racial issues presented to the Court was arguably more ambiguous and less distinguished.[11] For example, while Brandeis’ voting patterns showed a clear aversion towards racially-biased criminal trials,[12] he twice voted with the Court’s majority in upholding “all-white” primaries.[13] He also sided with the majority in cases upholding denials of U.S. citizenship to persons of Japanese and Indian ancestry.[14] Likewise, he voted to sustain “separate-but-equal” educational facilities for students divided on the base of race.[15]

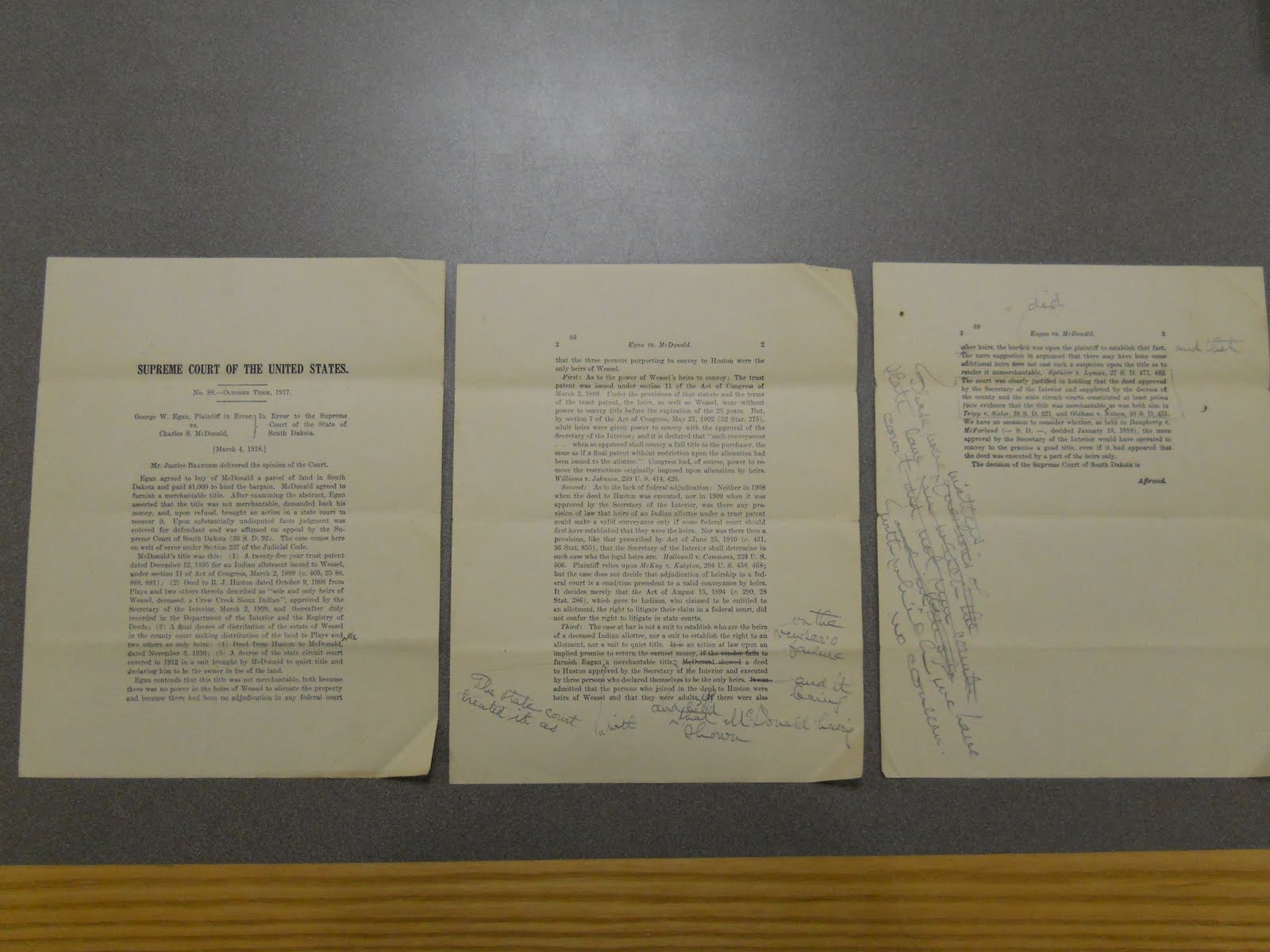

The collection includes first-print copies of several of Brandeis’ Supreme Court opinions, many bearing his handwritten editorial comments. These cases cover such diverse materials as Indian affairs,[16] commercial law,[17] anti-trust regulation,[18] probate law,[19] immigration and naturalization,[20] property,[21] and free speech.[22]

The collection includes first-print copies of several of Brandeis’ Supreme Court opinions, many bearing his handwritten editorial comments. These cases cover such diverse materials as Indian affairs,[16] commercial law,[17] anti-trust regulation,[18] probate law,[19] immigration and naturalization,[20] property,[21] and free speech.[22]

Perhaps controversially, Brandeis did not abjure from social and political causes while on the bench.[23] While he had been largely disinterested in Judaism in his youth, the anti-Semitism he suffered as he became an increasingly public figure, coupled with his professional involvement with Jewish groups, led Brandeis to take an interest in Zionism. He eventually became a leader in the movement to establish a Jewish state and, as many of the letters contained in the collection attest, continued to press the Zionist cause throughout his judicial career. Indeed, despite disputes with the newly formed World Zionist Organization, Brandeis remained a presence in the movement for the rest of his life.

The correspondence files reflect this, with Brandeis devoting a significant portion of his family and public correspondence to Zionist issues. In some instances, such correspondence reflects Brandeis’ stature within the movement (as well as prophesying the future Brandeis University). On January, 1931, Abraham Sakier proposed to Brandeis the idea of “an American strictly secular first-class university whose faculty and student body shall be predominantly Jewish… “[T]he name of this university,” Sakier suggested, “should be the ‘Brandeis University,’ because you are the greatest Jew in the history of this country.” Brandeis appears to have balked at the idea, however, as indicated in a later follow-up letter from Sakier.

The correspondence files reflect this, with Brandeis devoting a significant portion of his family and public correspondence to Zionist issues. In some instances, such correspondence reflects Brandeis’ stature within the movement (as well as prophesying the future Brandeis University). On January, 1931, Abraham Sakier proposed to Brandeis the idea of “an American strictly secular first-class university whose faculty and student body shall be predominantly Jewish… “[T]he name of this university,” Sakier suggested, “should be the ‘Brandeis University,’ because you are the greatest Jew in the history of this country.” Brandeis appears to have balked at the idea, however, as indicated in a later follow-up letter from Sakier.

At times, Brandeis’ correspondence reveals surprising insights about his interactions with other powerful jurists and politicians. For example, Brandeis appears to have formed a warm regard for Attorney General and future Supreme Court Justice James McReynolds. On March 2, 1914, for example, Brandeis wrote that “McReynolds was very intelligent in his criticisms of the [antitrust and trade commission] bill[s] … but he is very conservative.” On May 23 of the same year, Brandeis wrote that “The attacks on [McReynolds] are fierce and not justified.” He explained that Robert La Follette, the son of William La Follette (both men were close friends with Brandeis and feature prominently in his correspondence), who would eventually serve as a U.S. Senator for Wisconsin in his own right, “has little patience with my sympathetic judgment of him & thinks it does little credit to my intelligence.”

La Follette may well have been the better judge of character in this instance. McReynolds was an inveterate anti-Semite, who would often leave the Supreme Court conference room rather than listen to Brandeis express his views.[24] Indeed, the Supreme Court did not pose for its customary portrait in 1924 “because McReynolds would not sit next to Brandeis as protocol required[.]”[25] As Brandeis biographer Melvin I. Urofsky notes, McReynolds was “possibly the most unpleasant fellow ever to sit on the high court.”[26]

In 1932, Brandeis resigned at the age of 82. Spending much of his remaining time at his vacation home in Chatham, Massachusetts, he continued to correspond with and advise influential figures. He died from a heart attack in Washington, D.C., on October 5, 1941. The collection houses a large number of condolences, many from influential public figures, reflecting Brandeis’ standing in the legal and political communities and his enduring significance in American public life.

April 29, 2011

Notes:

- See, generally, Melvin I. Urofsky, Louis D. Brandeis: A Life (New York: Pantheon Books, 2009).

- 208 U.S. 412 (1908).

- Louis Brandeis and Samuel Warren, “The Right to Privacy,” Harvard Law Review, vol. 4 (1890): 103

- 277 U.S. 438 (1922).

- See Urofsky, Brandeis: A Life, 631-632.

- Urofsky, Brandeis: A Life, 458.

- See William G. Ross, “The Ratings Game: Factors that Influence Judicial Reputation,” Marquette Law Review, vol. 1996 (1996): 401, 403 (noting that Brandeis, along with Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes and Chief Justice John Marshall, is consistently rated as one of the greatest Supreme Court Justices in history).

- See, e.g., Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616 (1919); Whitney v. California, 274 U.S. 357 (1927).

- 304 U.S. 64 (1938).

- Cf., Urofsky, Brandeis: A Life, 623.

- See Christopher A. Bracey, “Louis Brandeis and the Race Question,” Alabama Law Review, vol. 52 (2001): 859 (critiquing Brandeis’ record on race issues).

- See, e.g., Moore v. Dempsy, 261 U.S. 86 (1923); Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45 (1932).

- Nixon v. Herndon, 27 U.S. 536 (1927); Nixon v. Condon, 286 U.S. 73 (1932).

- See Ozawa v. United States, 260 U.S. 178 (1922); United States v. Thind, 261 U.S. 204 (1923).

- See Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U.S. 78 (1927) but see, also, Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1938) (holding a whites-only, state-run law school had to admit a black student as there was no separate blacks-only law school in the state).

- McCurdy v. United States, 246 U.S. 263 (1918); The Duncan Townsite Co. v. Lane, 245 U.S. 308 (1917).

- Bethlehem Steel Co. v. United States, 246 U.S. 523 (1918).

- Board of Trade of Chicago v. United States, 246 U.S. 231 (1918).

- Bilby v. Stewart, 246 U.S. 255 (1918).

- United States v. Ness, 245 U.S. 319 (1917).

- Egan v. McDonald, 246 U.S. 227 (1918); Sears v. City of Akron, 246 U.S. 242 (1918).

- Schaefer v. United States, 251 U.S. 466 (1920) (concurring in part, dissenting in part).

- See Bruce A. Murphy, The Brandeis-Frankfurter Connection: The Secret Activity of Two Supreme Court Justices (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982) (critiquing the scale of Brandeis’ extrajudicial activities during his time on the bench).

- See, Melvin I. Urofsky and David W. Levy, eds., The Family Letters of Louis D. Brandeis (Norman, OK: University of Nebraska Press, 2002), 249, n. 1.

- Urofsky, Brandeis: A Life, 479.

- Urofsky, Brandeis: A Life, 388.