The Secret in the Suitcase

Amid the long-ignored keepsakes of his grandfather's life, Ted Gup '72 finds a tale that strikes a chord with recession-weary readers.

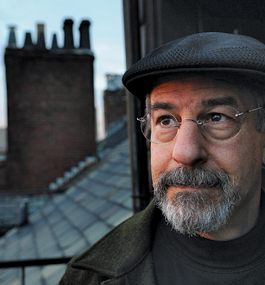

Bradley E. Clift

Ted Gup ’72 discovered more than 150 letters and dozens of canceled checks in a suitcase that had been forgotten for 75 years.

by Barbara Howard and Theresa Pease

It was late 1933, the depths of the Great Depression. The unemployment rate in the once-bustling industrial town of Canton, Ohio, a magnet for people from all over the world seeking

work, was 50 percent. Banks had failed, taking people’s life savings with them. Some children were going to bed hungry; some were dying of starvation or tuberculosis. Christmas cheer seemed a long-ago memory.

But on Dec. 18, a brief article on the front page of the local newspaper, the Canton Repository, called attention to an ad inside. The 158-word item, no larger than a playing card, was dense with text, acknowledging the pain involved in suffering a reversal of fortune and the humiliation of needing to ask for help to feed one’s family. The writer encouraged those down on their luck to send a letter describing their hardships and offered to supply modest help to struggling families “so they will be able to spend a merry and joyful Christmas.” It was signed “B. Virdot.”

Flash forward 75 years to Kennebunk, Maine, where award-winning investigative journalist Ted Gup ’72 was visiting his 80-year-old mother. Before he left, the Ohio-bred woman retrieved from her attic a faux leather suitcase full of vintage papers that had belonged to her father. She had no idea what the valise contained, but, knowing of Gup’s interest in family history and his passion for research, she wanted her son to have it.

Arriving home at his cabin in coastal Bucksport, Gup stashed the collection under his bed with little thought. But a few days later, he decided to take a look. Inside were more than 150 handwritten letters and dozens of canceled checks. The letters — some from formerly prominent Canton citizens who had employed hundreds of people — told of lost jobs, lost homes, lost self-esteem, lost hope. Each letter was addressed to, and the checks were signed by, B. Virdot. The name meant nothing to Gup. But the stack of papers yielded a valuable clue: Reading a yellowed page from the Canton Repository, the Brandeis grad realized “B. Virdot” was an anonymous donor who had wished to help his neighbors without embarrassing or obligating them. His curiosity piqued, Gup set out to unravel the secret behind the suitcase.

It didn’t take Gup long to realize the mysterious benefactor was his grandfather, whom he had known as Sam J. Stone, a Canton businessman. The B. Virdot pseudonym combined the names of Stone’s daughters: Barbara, Virginia and Dorothy. Originally, the quiet philanthropist had planned to send $10 checks to some 75 families. When he read the many expressions of need, though, Stone decided to help 150 families with $5 contributions.

While the gesture may sound feeble today, $5 in 1933 could feed a hungry household for some time, provide holiday gifts to kids who would otherwise go without, or put coal in the furnace of an icy-cold dwelling. It could supply brand-new footwear to once-affluent families who had been making their old shoes last by adding inserts cut from discarded tires. It could even save a discouraged soul from despair.

Reflecting on Stone’s generosity, Gup explains, “The built-in government social safety nets we have today did not exist in 1933. Back then, if you lost your job, you could very well see your children starve to death, or they’d be put into orphanages. Jails were full of Depression inmates, people desperate enough to cross the line and steal to feed their families.” For the most part, though, Canton’s proud displaced workers were not desperate enough to openly accept what they saw as handouts. For his grandfather’s correspondents, appealing to charity could only be done from behind a veil of shame.

Intrigued, Gup — who has written for The New York Times, Washington Post, Smithsonian and Village Voice, among other publications — set out to document who the letter writers were and what had become of them. He searched public records, newspaper clippings, cemetery and tax records, and dozens of other sources. He conducted more than 500 interviews with children and grandchildren of the original writers; he even met one of the correspondents, a budding adolescent when she applied to B. Virdot for help.

Their history is chronicled in Gup’s new book, “A Secret Gift.” The volume, published by Penguin Press in October, hit the market at just the right time, when recession-weary readers were yearning for tales of hope and miraculous redemption. Media attention for the book was lavish, and Gup received offers to speak in locations that ranged from the Boston Athenaeum to the Maltz Museum of Jewish Heritage in Cleveland, and from the Smithsonian Institution in Washington to the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum in Hyde Park, N.Y. The heartening narrative has sparked discussions of again-pertinent issues like need, compassion, hope, responsibility and human kindness.

The author is not convinced the timing was a mere coincidence.

“Here this suitcase survives 75 years and finds its way into the hands of a reporter in the midst of the greatest recession since the Great Depression,” says Gup, who now heads the Emerson College journalism department. “If you believe things were meant to be, this was meant to be.”

Readers relate to the pathos in letters like that of Edith May, a young African-American mother who wrote plaintively of feeding her family of five on $2 a month, but doubted her message would arrive because she had no money to pay for the needed 3-cent stamp. Following up, Gup managed to track down Edith May’s daughter, Felice, who remembered the hard times.

“She told me her father trapped skunks and sold the pelts for food, clothing and animal feed,” says Gup. “He would come home with his eyes swollen shut because he’d been sprayed. She remembered he smelled awful.”

Although she was unaware of the B. Virdot gift, the revelation did explain one early memory for Felice, whose birthday is two days before Christmas. Her family seldom traveled into town, but Felice recalled that on her fourth birthday she was taken to a five-and-dime store to pick a toy. She chose a toy horse with a pull string. Today she raises miniature horses, says Gup.

As he traced those who wrote seeking help, Gup uncovered another family secret. He had been told his grandfather was born and raised in Pittsburgh, but he found Sam Stone was actually a 1902 refugee from the Romanian pogroms. Originally named

Finkelstein, Sam came to the United States at age 15 and worked his way up from laboring in a coal mine to spearheading ventures in real estate and retailing. He teetered on the brink of bankruptcy after the crash of 1929. By 1933 he had recovered, and not only was earning a solid living from Stone’s Clothes in downtown Canton but was in a position to purchase a chain of nine menswear stores. It struck a fanciful chord with Gup that his grandfather’s neighbors little suspected their Christmas benefactor was a Jew.

Today, Stone’s bountiful example continues to reverberate in Canton, which is again suffering from a deep recession. Inspired by the story of “A Secret Gift,” another anonymous donor has stepped forward. In an item placed again in the Canton Repository on Thanksgiving Day, the latter-day philanthropist offered $100 to 150 recipients. This seed money generated additional donations, and before long more than $20,000 had been collected to brighten the holidays of some 200 families.

Like the original, the Thanksgiving Day notice was signed

“B. Virdot.”