Small Pox, Large Issues

A Brandeis author chronicles a historic tension between state power and individual liberties.

Special Collections, Brandeis University Library

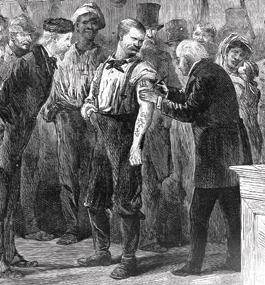

“Vaccinating the Poor,” Harper’s Weekly 1872

Since his undergraduate years at Yale in the 1980s, associate professor of history Michael Willrich has been fascinated by the Progressive Era (1890–1920). In 1997, he earned a doctorate at the University of Chicago, where his interdisciplinary studies included American legal history and the development of legal systems worldwide. At Brandeis he teaches graduate and undergraduate courses on American political and legal history, crime and punishment, and social politics, as well as the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era. Willrich’s first book, “City of Courts: Socializing Justice in Progressive Era Chicago,” was published to critical acclaim in 2003 by Cambridge University Press. Below, the award-winning historian discusses with Brandeis Magazine editor Laura Gardner his new publication, “Pox: An American History” (Penguin Press, April 2011). The book tells the story of the nationwide fight against the great wave of smallpox epidemics that struck America and its overseas territories at the start of the 20th century — a fight that spurred an important civil liberties debate and engendered widespread opposition to compulsory vaccination.

Why did you settle on the Progressive Era as the focus of your research?

Everything is in motion during the Progressive Era. When you look at old photographs of the city streets in places like New York, Chicago and Boston, you see horse-drawn carriages competing for the road with streetcars, the earliest automobiles, bicycles and untold numbers of pedestrians. At the turn of the century, Americans were also responding to the rise of a much more powerful government in their nation by asserting their claims on a whole set of rights and freedoms, including the right to medical liberty. It’s a transitional moment in American society — in culture and politics, in moral thinking, and in law. It’s also a period when Americans come to a powerful sense of themselves as an industrial society.

Why a history of smallpox?

I had planned to write a book about civil liberties struggles during the early 20th century, looking at different areas: the fight against compulsory education, the draft, people who resisted the census, and the eugenics movement. But I started by researching a legal case, Jacobson v. Massachusetts, that challenged compulsory vaccination and ultimately went to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1905. After reading around the case in newspaper accounts and public health reports, I realized the high court was making its landmark decision about the legitimate reach of publichealth authority on the heels of an incredible smallpox epidemic that swept across much of the United States. I became more and more interested in that epidemic, and all the other areas became less interesting to me. I wanted to tell the best story about the larger question of the balance of individual liberty and public power in the mod-ernizing nation. That story was smallpox.

|

|

|

Historian Michael Willrich |

What sets smallpox apart from other viral killers?

Smallpox has been eradicated globally, so most people don’t know much about it. Smallpox was the worst killer in human history; it is estimated to have killed some 300 million people around the globe in the 20th century alone. It was truly a hideous disease; even people who survived it were very likely to be disfigured. It was the most feared disease in 19th century America because the virulent form killed roughly 30 percent of the people who contracted it. Even by the early 20th century, when vaccination existed and there were powerful efforts to eradicate it or hold it in check, it occupied a very large place in people’s imaginations.

You write that, around 1900, Americans witnessed the emergence of a new, milder form of smallpox that killed only 1 percent of those who contracted it, prompting many to doubt that the disease spreading like wildfire among them was indeed smallpox.

Exactly. At the same time, there were major outbreaks of the terrible, virulent form of smallpox in many places, among them New York, Boston and Cleveland, so public health officials felt they had an urgent duty to vaccinate the population. And these officials also believed that, at any minute, even the milder form of smallpox could break out into a horrific epidemic of the old, incredibly lethal smallpox. They had no way of knowing that the new strain of virus would continue to stay mild instead of becoming more virulent. So a clash developed between the public health community, which believed that compulsory vaccination was the only way to check this horrible disease, and the many Americans who doubted the disease altogether and feared the risks of vaccination. At a time when there were few governmental controls on vaccine manufacturing, those health risks were very real.

One figure in your book, a visionary health official named C.P. Wertenbaker, came to realize that persuasion and

public education could succeed in achieving widespread immunization, while coercion — particularly when accompanied by a billy club or a bayonet — would only stiffen popular resistance to vaccination, creating a backlash.

Wertenbaker was a surgeon with the federal Public Health and Marine-Hospital Service. He traveled to smallpox-infected communities across the South and tried to get the people to accept vaccination. What I came to admire most about Wertenbaker was his candor. In public squares, before large audiences of ordinary people, he spoke out about the horrors of smallpox and about the risks and benefits of vaccination. By the time he was done talking, many people were rolling up their sleeves.

Recently, there has been a resurgence of antivaccination sentiment among parents, fueled largely by a now-discredited 1998 medical journal article suggesting a possible link between the MMR vaccine and autism. Can we draw any parallels from what was going on in 1900?

Members of the public health community — and the journalists who cover these issues — need to understand that the public’s underlying fear about vaccination technology is deep-seated. Smallpox vaccine technology was developed in the 1790s, long before germ theory gained acceptance, and there were real risks associated with vaccination, from swollen arms that caused days or weeks of lost work, to cases where contaminated vaccine caused death. Now, of course, vaccines are much safer and subject to extensive regulation. But government-mandated vaccines have also grown far more numerous. And until officials understand that people’s long-held fear about vaccination is more than just anti-scientific “denialism,” even exposing the allegedly fraudulent research behind the vaccine-autism scare may not change people’s attitudes.

Vaccination has proven to be one of the greatest health advances in history — and not only because it helped eradicate smallpox worldwide by 1980. What should public health leaders do to promote its acceptance?

Instead of vilifying the antivaccination minority, the public health community needs to grow the provaccine majority. Scientists and public health officials have an obligation to work continually to persuade the public through education. Leaders must understand that their job is never done, and not everyone views these technologies as entirely benign. We need to have a national conversation about the risks and benefits of vaccines. This is the challenge of science in a democracy, and it’s one that is not going to go away.