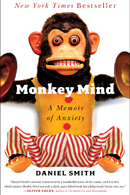

King of Angst

Daniel Smith ’99 proves the best way to beat back the grasping tentacles of anxiety is to write a critically acclaimed, outrageously funny memoir about it.

Photo by Mike Lovett

Anxiety is an affliction with a rich pedigree. Its sufferers have included Abraham Lincoln and Sir Isaac Newton, pioneering psychologist William James and Academy Award-winning actress Kim Basinger. Most of the estimated 40 million clinically angst-ridden Americans, of course, are ordinary people who suffer episodically or chronically from a constellation of debilitating symptoms like panic attacks, irrational fear and unsubstantiated worry.

|

In “Monkey Mind: A Memoir of Anxiety,” Daniel Smith ’99 gives voice — by turns poignant and petulant, but almost always comedic — to chronic anxiety’s paralyzing effects. Here is a sufferer who shielded his armpits with maxi pads to keep his profuse sweating in check. Who once became nearly unhinged trying to choose between ketchup and barbecue sauce at a Roy Rogers condiments counter. Who fled to the bowels of Goldfarb Library whenever an “infestation” of students threatened his equilibrium.

As Smith explains in the book, “a person in the throes of monkey mind suffers from a consciousness whose constituent parts will not stop bouncing from skull-side to skull-side, which keep flipping and jumping and flinging feces at the walls and swinging from loose neurons like howlers from vines.”

In the “Monkey Mind” excerpt below, Smith conjures his first year at Brandeis, deep in the throes of anxiety.

There are two types of anxiety sufferers: stiflers and chaotics.

Stiflers are those who work on the principle that if they hold as still, silent and clenched as possible they will be able to cut the anxiety off from its energy sources, the way you cinch off the valve on a radiator. It isn’t hard to spot a stifler. They tend to look haunted and sleepless, like combat veterans, and they are more likely to chain smoke and pour themselves a drink within five minutes of getting home from work.

Chaotics, by contrast, work on no principle whatsoever. Although chaotics are sometimes stiflers when alone, around people, and especially in tense interpersonal situations, they are brought into a state of such high psychological pressure that all the valves pop open of their own accord, everything is released in a geyser of physicality and verbiage, and what you get is a kind of shimmery, barely stable equilibrium between internal and external states, like in those rudimentary cartoons where the outlines of the characters continuously squiggle and undulate. Sometimes the behavior of chaotics is interpreted by laymen as emotional honesty, but it’s almost always involuntary. Chaotics are merely stiflers with weak grips.

|

|

Sidebar Story |

|

When I went off to Brandeis, I wanted very much to be a stifler. Partly this was because of pride. Partly, however, it was because going off to college isn’t just a journey into dread-inducing freedom. It is also a journey into a sudden, stultifying constriction of one’s personal space — which is to say, the opposite of freedom. This is what makes college so precarious a transition for your less robust types. It’s an anxiety double whammy: In the existential sense, college radically expands life’s possibilities; but in the nitty-gritty, flesh-and-bone sense, college throws you into cramped living quarters with people you have never met and share no genetic affiliation with but whom you have no choice not only to endure but also to shower with, brush your teeth alongside and defecate three feet away from. After close to two decades of cohabiting exclusively with parents and siblings, this shift can cause a fair amount of psychological friction. This is particularly true because in freshman dormitories it is something of an imperative to present yourself as poised and confident even if you are in fact bilious, angst-ridden and actively decompensating. In this way, the dorms are not unlike army barracks, right down to the bunk beds, the thin mattresses and the young men weeping quietly into their pillows.

By the end of my fourth week at school round-the-clock anxiety and the addled half-sleep that comes with it had eaten so thoroughly into my defenses that it was nearly impossible to keep the tears at bay. There was simply nowhere to escape to. At home when I was anxious I could count on two places in which I was free to freak out as extravagantly as I wanted: my bedroom and the bathroom. In the dormitory, I discovered, it was almost impossible to find the solitude a real anxiety attack demands.

My parents said I could come home with them if I wanted. It was the easiest thing there was. I would just need to pack my things and we’d head for the interstate. We could call the registrar’s office from the road. But I decided to stick it out, and from the way my parents nodded their heads I could tell they were pleased. What purpose would I serve at home? What good would it do me to putter aimlessly around the house? I would sleep for twelve hours a day and read for a few more. What would I do with the remaining nine?

page 2 of 3

But there was a catch. If I was going to stay at school, my mother insisted, I would have to seek professional help. “There are two-and-a-half months between now and winter break,” she said. “There’s no reason you should have to get through that time on your own. A trained therapist, someone to talk to and learn from, could be an enormous help. It’s the only way, sweetheart.”

The therapist was the only person I have ever seen outside of silent movies who stroked his beard to illustrate that he was thinking. He was slim and short and 30 at the oldest. His office, which I gathered he shared with several other fledgling shrinks, resembled the office of a teaching assistant in one of Brandeis’ less respected academic departments. It wasn’t much larger than a toolshed, and not much neater. Tall piles of manila folders lay on a series of cheap aluminum shelves. Case notes, I assumed — the life stories and weekly unravelings of the furtively afflicted. There was barely enough space in the room to fit the chairs on which we sat, facing each other. When the therapist hitched up his pants, our knees kissed.

“So what brings you here today?” he asked.

My heart fell. “What brings you here today?” It was such a hackneyed question, a line from a bad script. Couldn’t he have done better than that? It didn’t seem to bode well. Since he was only my second therapist, I didn’t yet know that all therapeutic openings are hackneyed. “How can I help you?” “Tell me a bit about yourself.” “What’s bothering you?” Compared to the alternatives, “What brings you here today?” is actually pretty good: open-ended, present-tense, oriented toward the petitioner rather than the petition.

“I suffer from anxiety,” I said, and then a stiff jolt of awareness struck me somewhere in my abdomen, for I’d never said it like that before. I’d never used the word in that kind of sentence. I’d used it, usually in adjectival form: “I’m feeling anxious.” I knew that all the words that applied here and there to my experience — sadness, depression, nervousness, despair, dissociation, obsession, distraction, self-awareness, hysteria, angst, dejection — were satellites orbiting around the main word, the main event: anxiety. But saying “I suffer from anxiety” to a therapist changed the word from a descriptor to an act of acquiescence — a bowing to the authority of pathology.

Then I was surprised again by what the therapist did next. The poor man must have been as nervous as I was, because after nodding sympathetically for a few seconds he reached to a shelf behind him, pulled down a thick psychology textbook and proceeded to flip through it. When he had found the page he was looking for, he gave his beard a few languid strokes and read.

“Anxiety,” he said. “Anxiety is a relatively permanent state of worry and nervousness occurring in a variety of mental disorders, usually accompanied by compulsive behavior or attacks of panic.” He raised his eyes. “Is this what you’ve been feeling?” he asked. “Would you say this describes your experience accurately?”

I nodded. “Yes, I think so. I think that about describes it.”

He turned the page. His beard received further ministration.

“There’s a table in here,” he said. “A list of criteria that will help us determine whether what you’re feeling is ... well, whether it’s a problem or not. I’m going to read these aloud to you. Is that all right?”

“Yeah. OK.”

“Here we go then,” he said. “Number one. Would you say that you’ve been anxious more often than not for the past six months?”

page 3 of 3

“Uh, no. Not really. It’s pretty new. Well, this time it is. I’ve had it before. I’ve gone through it before. But this time it’s only been for about a month, since school started. But it’s been bad, really bad. Like, constant.”

“So that’s a ‘no’ then.” He twisted over to his desk and scribbled a note. “That’s good. That’s a good sign. Let’s go on to number two. Would you say you have difficulty controlling your worry?”

“Oh, yeah. Definitely. Yes.”

He scribbled again. “Three. Please answer yes or no to the following symptoms. Do you feel restless, keyed up or on edge?”

“Yes.”

“Are you easily fatigued?”

“Yes.”

“Do you have difficulty concentrating?”

“Yes.”

“Are you irritable?”

“Yes.”

“Do you feel any muscle tension?”

“Yes.”

“And finally, do you have sleep disturbance?”

“Sleep disturbance?”

“Trouble getting to sleep, trouble staying asleep, unsatisfying sleep.”

“Yes.”

“Right, six out of six.”

“Is that bad?”

He affected a neutral tone. “There’s no good or bad here. We’re just trying to determine what’s troubling you. Now, then, question number four. ... Well, four I can’t really ask you. Four is a little technical. Let’s move on to five. Would you say that your anxiety causes you impairment in social, occupational or other important areas of functioning?”

I felt like I might cry if I spoke, so I nodded.

“Is that a yes?”

I nodded more vigorously. He made an empathy face. “I know this is hard. There’s not much more.”

I nodded.

“Six. Is your anxiety due to the direct physiological effects of medication, substance abuse or a general medical condition such as hyperthyroidism, and is it exclusive of a mood disorder, a psychotic disorder or ... well, wait. I’m seeing now that this one might be hard for you to answer, too. So let’s just — let’s just skip it.”

I started to cough, to beat back the tears.

“Maybe we should just” — he was thumbing through the book now as I coughed louder — “maybe the thing to do would be” — he flipped to the index, scanning it with one hand while with the other he played with his beard — “maybe we should just talk a little then.”

“But do you think —”

“See where it takes us. Just discuss what you’ve been feeling.”

“Do you think —”

“Hash it out.”

“Do you think there’s, like, something wrong with me?”

He leaned way back in his chair. Our knees touched again.

“Don’t quote me on this,” he said. “But I’d say there’s definitely something off kilter.”

Adapted from “Monkey Mind” by Daniel Smith. Copyright © 2012 by Daniel Smith. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.