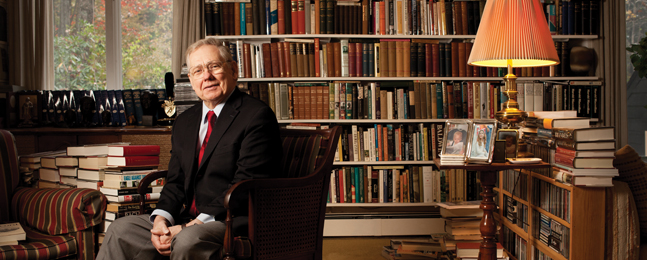

History Lessons

In his half century of teaching at Brandeis, David Hackett Fischer has become one of the nation’s most respected historians and one of the university’s most influential professors.

Photo by Jörg Meyer

A little more than a half century ago, historian David Hackett Fischer was a newly minted PhD from Johns Hopkins University with offers in hand from four universities, including one from a very young, brash institution in Waltham.

Clearly in demand, the ambitious historian set out to do what any well-trained scholar would do: conduct primary research about each potential employer.

To his amazement, Fischer says, at the first “very old and eminent school in the Northeast” he met the president and the dean — a sure sign a meaty historical discussion with two intellectual heavyweights was imminent, or so he thought. Instead, the pair was more interested in “who my grandparents had been and where I bought my sport coat,” Fischer recalls with a laugh. Strike one.

Next, Fischer says, he visited a Southern university, “a great and honorable place,” where he was delighted to learn that some members of the history department had a long-standing tradition of convening every Monday evening to discuss the great topics of the day. During his visit, the topic would be capital punishment. Fischer duly marshaled his arguments. Once the discussion started, however, Fischer discovered the focus wasn’t on the pros and cons of capital punishment. The debate was about the best methods of execution. Strike two.

The third university Fischer traveled to was a large Western university with its very own airport. There, Fischer learned, he would be enlisted to teach the introductory American history course. So far, so good. Then he asked about enrollment in the course, and discovered he would be instructing 1,000 students. Strike three.

When Fischer finally arrived on the Brandeis campus, he walked to the then new faculty club, where he was scheduled to meet Professors Leonard Levy and John Roche, both experts on constitutional history. Caught up in a passionate debate about the finer points of substantive and procedural due process — “fists crashed on the table, and coffee cups went leaping in the air,” recalls Fischer — neither Levy nor Roche noticed the visitor.

Finally, Fischer recounts, “Professor Levy glanced over at me and asked, ‘Why are you here?’ I thought, This is the place for me.”

This year, Fischer, University Professor and Earl Warren Professor of History, marks 50 years at Brandeis. Thousands of students, 101 semesters, countless awards and honors — including a Pulitzer Prize — and numerous hugely influential books later, the self-described storyteller says he’s stayed at Brandeis for the same reason he came in the first place: “Teaching and learning are at the heart of this enterprise.”

As a teacher, Fischer is renowned for his interest in his students and his subject matter. “His passion for history really does come across, in his tone and his focus,” says Josh Kaye ’13, a double major in history and Near Eastern and Judaic studies. “He doesn’t throw things when he talks, but you can sense his excitement.”

As a scholar, Fischer has written a constellation of books spanning continents, epochs and cultures, including “Washington’s Crossing,” which earned him his Pulitzer; “Champlain’s Dream”; “Albion’s Seed”; “Liberty and Freedom”; and, most recently, “Fairness and Freedom.” Despite their range, all his books are connected by the central inquiry of his scholarship: How do open systems work?

Still researching and writing at a breathtaking clip, the septuagenarian recently traveled to five African countries for his next book, which explores the ways vernacular African culture came to America through the travail of slavery.

Original research being the gold standard in historical scholarship, to mark the Fischer half century Brandeis Magazine sought out a handful of primary sources, all of whom were eager to offer their own narrative of a man one of them rightly describes as “a national treasure.”

— Laura Gardner

|

|

Emanuel Leutze’s painting of Washington crossing the Delaware spotlights a great and noble man, who, says Fischer, invented an ingenious idea of open leadership to unite an army of cantankerous Americans in a common cause. |

Grant Wood’s painting “Paul Revere’s Ride,” like the Longfellow poem, celebrates a great American loner. In his “Paul Revere’s Ride,” Fischer reveals a great American “joiner,” who brought people together at a pivotal moment.

page 2 of 6

Revealing America’s outlines in our voluntary society |

| by Steve Whitfield |

What puts David Hackett Fischer in the very, very small circle of the nation’s most accomplished historians?

One striking virtue of his work is versatility. The variety and scale of his books is unmatched; perhaps no living scholar exceeds him in his ability to tap the enormous breadth of the national experience. In the various genres that illuminate the American past, he has also shown an equal flair for writing well — indeed, spectacularly well.

David began his career as a political historian. “The Revolution of American Conservatism” (1965), published three years after he began teaching at Brandeis, traces the ways that the privileged and well-born in the Federalist Party grappled with the need to adapt to a rambunctious republic. To prevail in American politics, conservatives had to show (or pretend to show) the common touch; it’s no wonder this study of partisan campaigns in the early republic continues to reverberate.

His second book, “Historians’ Fallacies: Toward a Logic of Historical Thought” (1970), exposes the murkiness with which even the most prominent American scholars interpret and present evidence. Graduate students, a New York Times book reviewer wrote in 1970, were “chortling in the stacks” as they read the book, which offers instruction in advancing a historical argument.

No book could be more different from “Historians’ Fallacies” than “Liberty and Freedom” (2005), an iconographic survey of how these two entwined yet distinctive ideas took graphic form and life. For most academic historians, such a volume might have represented a lifetime’s investment of research. David seems to have written these 851 pages without even working up a sweat.

For much of his career, however, David could perhaps be most comfortably classified as a social historian, revealing the texture of the institutions and the proclivities of the diverse people who have formed our “voluntary society.” America’s outlines could be discerned in the origins of the republic, which is why David has tended to hug the shore of the 18th and early 19th centuries.

His mastery of the literature of early American history is not synthetic; his perspectives are fresh. Consider “Paul Revere’s Ride” (1994), for instance. The author notes the slowness with which a distinct American nationalism emerged, so that, in April 1775, Paul Revere still thought of himself as British, making it impossible that he would have warned, “The British are coming!”

David’s two most recent books install the United States within a wider perspective. “Champlain’s Dream” (2009) starts in France then settles in Canada, identifying the differences between the two North American nations in the high-stakes ways of war and peace. “Fairness and Freedom” (2012) goes farther, crossing the Pacific to contrast the democratic cultures of the United States and New Zealand. Many manifestoes advocate the benefits of comparative history; David Fischer actually practices it.

Among David’s distinctive gifts is his knack for tapping into conceptual problems and particular episodes that have contemporary relevance. “Albion’s Seed” (1989) proposes that the early inhabitants of British North America represented considerable divergences of belief and behavior, faiths and folkways.

In 1992, campaign strategists for Gov. Bill Clinton and Sen. Al Gore read “Albion’s Seed” to learn more about the regional nuances to which successful candidates have to be attuned if they are to appeal to the white voters of Anglo-Saxon ancestry upon whom electoral politics so often pivots.

A dozen years later, “Washington’s Crossing” (2004), David’s Pulitzer Prize-winning account of the general’s journey across the Delaware River to win the battles of Trenton and Princeton, spotlighted the unprecedented humanity with which Washington insisted his army treat British and Hessian prisoners of war.

This invocation of an “American way of war” found its way into the post-9/11 debate about the Bush administration’s decision to repudiate the Geneva Convention, a debate about the propriety of torture that a nation that professes decency should never have found it necessary to conduct.

Such is David’s reputation among American historians that, when he joined a search committee to hire an environmental historian in American studies, one of the final candidates, who confided in me that he did not expect to get the job, went through the process, flying across the continent and back, so that he could tell his colleagues back home he had met David Hackett Fischer.

Steve Whitfield, the Max Richter Professor of American Civilization at Brandeis, specializes in politics and ideas in 20th-century America.

Photo by Jörg Meyer

page 3 of 6

Esprit de corps |

| by Ann Plane, PhD’95 |

The first time David suggested that my classmate and I go for a walk with him to talk about the readings we had completed for that week, we set off into the woodsy area on the perimeter of the Brandeis campus.

David set a blistering pace, making it hard to talk much and have any chance of keeping up. The golden light filtered through the autumn trees, the leaves crunched beneath our feet, and we clambered over fallen logs and up the stony outcroppings of this patch of New England while wrestling with the finer points of land tenure, naming practices, household structure and courts of law.

|

|

Sidebar Stories Imagination, courage and clarity |

|

That first year of graduate school had begun with a challenge: “Read faculty books!” David intoned, as he dropped a weighty copy of “Albion’s Seed” on the desk in front of me. The first-year seminar was equally memorable for the loads of volumes he would pull — magician-like — from his briefcase as he made his way through any given topic.

Every Monday night after our seminar, my classmates and I would repair to Franca’s for eggplant and ricotta pizza, to continue the discussion. David inspired a camaraderie and esprit de corps in all six of us that — along with the crispy crusts and melted ricotta — fueled our weekly digestion of the seminar experience.

For experience it was! David and his wife, Judy, opened their home to us, inviting us into a gracious world of conversation and challenge. Walking into their

lovely house, the walls rimmed with books that extended to every corner, I was struck anew by his energy, hunger for argument and enthusiasm for advancing the careers of Brandeis students. When you matriculated with David, you joined a long and illustrious line of students, nearly all of whom have made enduring contributions to our understanding of the past.

One lively day, I tagged along while he showed a foreign visitor around Concord and Lexington, tramping — again tramping — along the battle road, and working our way — the three of us — back into history. With David, it is always a history grounded in place, camaraderie and intrepid exploration, and for that I am ever grateful.

Ann Plane, PhD’95, is an associate professor of history at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Her current research focuses on dreams, visions and colonialism in 17th-century New England.

Brandeis Archives & Special Collections

Transcendental Learning: Fischer and a group of students at Walden Pond in Concord, Mass., in 1988.

page 4 of 6

Big questions, small tests |

| by Richard Rath, PhD’01 |

“What’s the big question?” When spoken by David, these four words carried all sorts of implications and caused considerable anxiety during my graduate school days. Did I have a big question? What constitutes bigness? Would my work make any difference in the endless historical debates I was trying to master or, going bigger, in the world? I spent a lot of time trying to figure out the big question in any project, and what it entailed.

After this quest had tangled me into knots, David provided the next piece of advice: “Put big questions to small tests.” Suddenly, the task was manageable again. I was not out to prove answers once and for all, just to chart out a little corner or two of the bigness. Learning to navigate between the big question and the small tests gave me a way to write something larger than a paper, something that cohered and remained manageable in the details.

David has always been the best sort of reader I could both hope for and dread. More than one project withered under his scrutiny. More, I am pleased to say, survived, much the stronger for it.

“With delight” is the only way to describe how David engages with ideas. Because he is widely read to a fault, nothing I came up with was ever entirely new to him; but if some part of it was, that was where our discussion began. Objections, counterarguments, logical flaws: The whole retinue of “Historians’ Fallacies” was brought to bear on the idea being discussed, always tempered by an abiding curiosity and interest.

His delight is, in fact, a delight in learning. For him to say he had picked up something new from our discussions was grand encouragement to a scholar just starting out. This joy in learning is what makes David a great teacher, and it is contagious.

I often hear an echo of something I’ve learned from David when I speak to students; often I imagine I hear it right down to the intonation. He, too, learned much of his wisdom somewhere, and was passing it on. Now it is my turn to do the same. I’m part of something grand, stretching who knows how far into the past and, I hope, into the future.

Richard Rath, PhD’01, is an associate professor of history at the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa. He teaches courses on early America, Native Americans, and the history of media and the senses, and is the author of “How Early America Sounded” (2003).

Brandeis Archives & Special Collections

Fresh Air Kids: Throughout his teaching career, Fischer has combined learning and a love of nature.

page 5 of 6

Role model and friend |

| by Raymond Arsenault, MA’74, PhD’81 |

My maternal grandmother, though tiny in stature, was no shrinking violet. A native Bostonian, she had strong opinions on just about everything, from the pitching woes of the Red Sox to my choice of graduate school. In 1971, when I received fellowship offers from the history departments of both Harvard and Brandeis, she looked me square in the eyes and said that surely no one, not even her eccentric grandson, would turn down the chance to study at Harvard.

Two weeks later, when I did the unthinkable, choosing Waltham over Cambridge, I tried to convince her I had made the right choice. The Brandeis history faculty, I explained, included several of the very best American historians.

To make my case, I showed her a recently published book with the audacious title “Historians’ Fallacies,” and assured her I had never read anything quite like it. The author, David Hackett Fischer, was as brilliant as he was brash — mixing history and philosophy with witticisms from Lewis Carroll’s “Through the Looking Glass,” all in an effort to scold the historical profession for its chronic disregard for logical analysis. Seeing a quizzical look on her face, I read her a back-cover blurb. “The wisdom is expressed with a certain ruthlessness,” the Yale historian Robin Winks warned. “Scarcely a major historian remains unscathed. Ten thousand members of the American Historical Association will rush to the index and breathe a little easier to find their names absent.”

My grandmother’s reaction was, I suppose, predictable. “Why on earth would you want to study with such a rude man?” she asked. “Do you really want to subject yourself to this kind of criticism?” Why, indeed? For a moment, I was almost ready to concede her point. But somehow I steeled my nerves and returned to the allure of truth-telling mentorship. Six months later, my poor grandmother went to her grave firmly convinced I had made a serious mistake.

Now, more than 40 years after that conversation, I still feel sad recalling her disappointment, yet I also look back on the decision to study at Brandeis with David and his colleagues as unquestionably one of the best decisions of my life. As a teacher and an adviser, David taught me to strive for the highest standards of scholarship, and his intellectual integrity and passionate pursuit of historical understanding have inspired and challenged me throughout my career. My primary role model, he has also become a treasured friend. No student could ask for anything more.

Raymond Arsenault, MA’74, PhD’81, the John Hope Franklin Professor of Southern History at the University of South Florida, St. Petersburg, is the author of several prize-winning books, including “Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice” (2006), part of the “Pivotal Moments in American History” series co-edited by Fischer and James M. McPherson.

page 6 of 6

A lion slaying historical pieties |

| by Allan Kulikoff, PhD’76 |

I entered the Brandeis graduate history program in 1969, eager to examine the lives of the dispossessed in early America. I knew David Fischer would be the best adviser I could have. Even though my fellow grad students shied away from him because of his fierce reputation — he was finishing “Historians’ Fallacies,” which skewered prominent historians for errors in logic and argumentation — I decided to work with him.

At our first meeting about my first-year research paper, he suggested I examine inequality by analyzing tax lists stored at the old Boston City Hall. I went there; a half dozen officials, including a city council member, told me that such lists didn’t exist. When I reported this to David, he told me to go back and find someone willing to admit they had the records. Ultimately, the key keeper of the sub-sub-basement showed them to me.

I spent innumerable hours copying data from the 1790 tax list onto cards (no laptops then!) in a dusty, damp 80-degree basement, with just one light bulb for illumination. My persistence paid off in data — and in the worst case of eczema I had ever had. Making computations on a huge adding machine (four-function calculators had just come out, but cost too much), I determined levels of inequality.

When I finished the paper — beyond the deadline — David urged me to submit it to The William and Mary Quarterly. But what about the title? The ones I came up with all sounded pedestrian. David suggested “The Progress of Inequality in Revolutionary Boston.” Not only did it fit my arguments and data, it had a sharp, ironic twist: “Progress” might simply mean “increase” or “growth,” but by the 18th century the word had taken on its modern meaning, “change in the right direction.” The article, submitted and published, won the best-article award that year, in no small measure due to David’s detailed, astute criticism.

In the decades since, I have tried to emulate David’s method with my own graduate students: Have lengthy discussions of source materials with them. Make strong criticism of their written work (particularly early drafts). Help them connect with other scholars.

It is hard to believe that David has spent a half century at Brandeis. I still see him as a young lion, out to slay historical pieties while making new and arresting interpretations of the American past.

Allan Kulikoff, PhD’76, is the Abraham Baldwin Distinguished Professor in the Humanities at the University of Georgia. He is currently working on a book titled “Ben Franklin and the American Dream.”