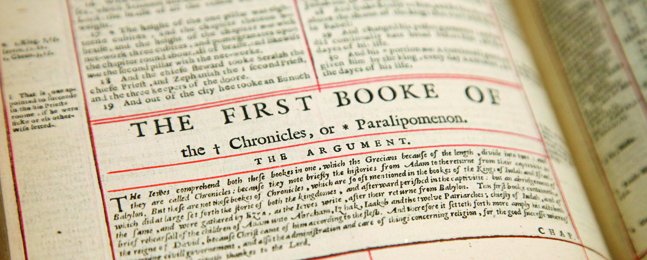

Beyond the Book of Chronicles

Brandeis professor takes Jewish scholarship where it has seldom gone: into the New Testament.

It may not come as any great revelation that Christians and Jews might differ in their interpretations of the Bible. What is more surprising is that two Jewish scholars, Marc Z. Brettler ’78, Ph.D.’86, the Dora Golding Professor of Biblical Studies at Brandeis, and Amy-Jill Levine of Vanderbilt University, should spend four years poring over the New Testament to analyze the ways the Jewish and Christian Bibles not only differ but agree.

The result of that study, “The Jewish Annotated New Testament,” includes essays by more than 30 contributors, all Jews. And, soaring beyond the response the publishers at Oxford University Press expected, the book shot to number 31 on Amazon’s top 100 best-sellers list after its release last fall. In the specific areas of “Bible and Other Sacred Texts” and “Christian Reference,” it ranked number 1. Following favorable coverage in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Christian Science Monitor and USA Today, Oxford had to arrange for several reprint editions.

Brettler had scored an earlier hit with his 2004 project, “The Jewish Study Bible,” which drew a wide array of Jewish scholars together to comment in a single text. In a telephone interview from Jerusalem, where he is on leave teaching and writing a commentary on the Book of Psalms, he said the success of the earlier volume signaled to him that the time was ripe for a long, close look at the New Testament by Jewish scholars.

“I was convinced,” he said, “that it was possible, even desirable, to be a religious person while being inspired by religious traditions other than your own. I am deeply moved, for example, by Paul’s words in the New Testament’s 1 Corinthians 13:4-8, where he says, ‘Love is patient; love is kind; love is not envious or boastful or arrogant or rude. It does not insist on its own way; it is not irritable or resentful; it does not rejoice in wrongdoing, but rejoices in the truth. It bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things.’”

While some Jewish commentators — including a reviewer on Amazon who admitted to not having read the book — objected to what they erroneously thought was an attempt to convert Jews to Christianity, Brettler said his purpose was not to argue the veracity or error of either tradition, but rather to increase neighbors’ understandings of one another’s faiths. “Christians,” he commented, “can benefit from understanding the Jewish roots of their own tradition. At the same time, most U.S. Jews have a poor knowledge of the New Testament, but it is too important a book in American culture for Jews to shy away from. If there is to be progress in Jewish-Christian relations, it is crucial to have a useful resource that highlights the Jewish background of the New Testament, issues of anti-Judaism, and the history of the split between Christianity and Judaism.”

What surprises emerged?

“I was most surprised,” Brettler responded, “by the strong sense of continuity between the two books and the sheer volume of similarities between the New Testament and rabbinic writings. I had known how Jewish some of the Gospels sounded, especially Matthew, but I was surprised at how Jewish in style and argument some of Paul’s letters are. I also was struck, in editing the annotations and essays, by the existence of cross-reference after cross-reference of New Testament text to either the Hebrew Bible or rabbinic literature.”

Seizing on a specific example of concurrence, Brettler noted that most Jews think of original sin — the belief that babies are born into the world with the stain of guilt already on their souls and must be cleansed through baptism — as an exclusively Christian notion. But in reading the text, Brettler was struck by the similarity to a passage in the Jewish Bible, where, in Psalms 51:7 (English 5), it says, “Indeed, I was born guilty, a sinner when my mother conceived me.”

The most satisfying part of the past several months’ experience, the professor added, was the realization that the book had struck a chord with many non-scholarly readers from both Christian and Jewish traditions. “It was gratifying,” he said, “to see that there continues to be a strong interest in religion in America, and that this interest is finally becoming broader. Jews are becoming interested in Christianity, and Christians in Judaism. I will be delighted if this book plays some role in that expanding interest.”