Depth of Field

Dan Perlman

by Laura Gardner

Across the millennia, great civilizations have risen and fallen. Others — just as complex and mysterious — continue to live on, largely unobserved, for countless eons.

Consider leafcutter ants in the genus Atta. Up to 8 million of these industrious insects live in a single self-sufficient colony, always situated in a warm, sunny clime, boasting full-time employment and other accouterments of the good life: plentiful food, lots of jostling camaraderie, nice housing and orgiastic, promiscuous sex — at least for one day.

In the evolutionarily ancient society of leafcutter ants, each colony may span 10 meters in diameter and extend more than 6 meters underground — the equivalent of the Roman Empire to the legions of this get-down-to-business insect. A bug’s life in this world is highly organized, even regimented, enabling a colony of tiny workers to strip an entire tree of its leaves in about 24 hours.

This is just the kind of dramatic civilization that fires up Associate Professor of Biology Dan Perlman, whose boyhood passion for all things Insecta planted a powerful love of nature in him. Later on, as Perlman began to look around (and not just under rocks), he noticed how interesting human behavior and social psychology were, too. Ultimately, these two intellectual threads would grow and intertwine in him.

Though he worked as a computer programmer after graduating from Yale, Perlman says (somewhat ironically) he realized in the early 1980s that “computers were a dying field and ants would always be here.” He then adds with total conviction, “I love insects, I love social behavior and so I decided to study insect social behavior — ants.”

Pursuing a doctorate at Harvard, where he studied with evolutionary biologist and legendary ant man E.O. Wilson and biologist Bert Hölldobler, Perlman completed his fieldwork in the late 1980s in Costa Rica. It was in the cloud forests of Monteverde that the biologist became spellbound by insect eggs. “What I realized was that if I was able to see single insect eggs on leaves when I walked through a forest, I was cued in,” he says.

Photography, an interest of Perlman’s since high school, became an indispensable tool in his research. Over time, it’s also become a distinguishing element of his teaching. For several decades, Perlman has studied — and chronicled in breathtaking, sometimes poetic photography — the lives of insects, as well as a Noah’s ark of wildlife and plants in their native habitats around the globe.

The bearded, bespectacled biologist estimates he’s taken some 250,000 photographs so far — photos that tell stories about mutualism, parasitism, life, death, transformation, predation, decay, social organization, habitat loss, sex — pretty much the top-10 list of topics most academics wish they could produce from their pedagogical arsenal. These are the kinds of stories that have kept even the most jaded students on the edge of their seat and resulted in numerous teaching awards for Perlman, who was recently appointed associate provost for assessment and innovation in student learning.

In these pages you’ll find a small sampling of the riches of Perlman’s photography. For more, visit the EcoLibrary, a website he started seven years ago to give students and teachers free access to materials that support learning about ecology, conservation biology and the environment.

“What I try to do in my photographs,” he says, “is to help people see things that they couldn’t see otherwise, that they haven’t seen otherwise, that they don’t know how to look for.”

And if you’re curious about the sex lives of leafcutter ants, turn to page 28.

page 2 of 10

|

A single corncob-shaped Heliconius butterfly egg hangs from the elegant tendril of a passionflower. This simple image belies a complex evolutionary history. Such a state of affairs at the tip of a tendril actually represents a detente in a long-running arms race between butterfly and plant, in which an evolutionary advance in one species is matched with a counteradaptation in the other. For example, the passionflower deploys nasty alkaloid chemicals to keep all hangers-on from eating its leaves, and it has nectar-secreting glands to attract protective ants. Over time, however, the butterfly has evolved to cope with the noxious chemicals and lay its egg at the end of a tendril, as far from the ants as possible. Why a single silky egg? The caterpillar that emerges from the egg is cannibalistic, making company lethal.

page 3 of 10

The Peaceable Kingdom

|

In the Serengeti of Tanzania, different species —— zebras, Thomson’s gazelles and impalas —— graze in what appears to be a fairly simple ecosystem of large herbivores. Look again. Perlman says the animals in this photo are both competing for and divvying up various grasses, with some eating the upper, coarse stems of grass, others eating the middle layer and some animals waiting until the tiny herbs at ground level are exposed. “In large measure these animals are slicing and dicing it, so they each have a slightly different niche,” says Perlman.

page 4 of 10

|

Hiding underground for 16 years and 11 months, sucking sap from tree roots to survive, may seem a cowardly way to grow up. But when you’re essentially spineless, lack any sort of chemical defense, are a lousy flier and represent a tasty morsel to many predators —— including humans —— it seems the most prudent thing to do. Welcome to the wacky world of the cicada, genus Magicicada. But even a timid 17-year-old cicada knows there’s safety in numbers. In the insect version of a “shock and awe” campaign, hundreds of millions of cicadas emerge en masse from their nymph shells, like this one, within the same 10-day period in year 17, easily overwhelming predators in sheer number.

page 5 of 10

|

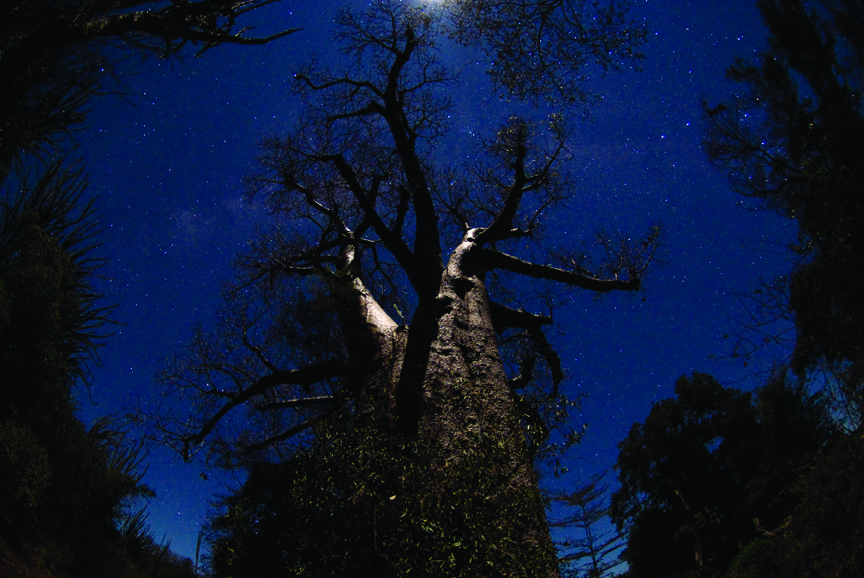

Of the eight species of baobab trees in the world, six are found only on the island of Madagascar, where Perlman shot this photo at night. The tree is known for its fabulous longevity —— some are believed to be well over a thousand years old —— and for its massive, stocky trunk, which conserves water during the dry seasons. The mythic tree even makes an appearance in Saint-Exupery’s classic “The Little Prince,” in which the main character struggles to keep a baobab from taking root on his asteroid.

page 6 of 10

|

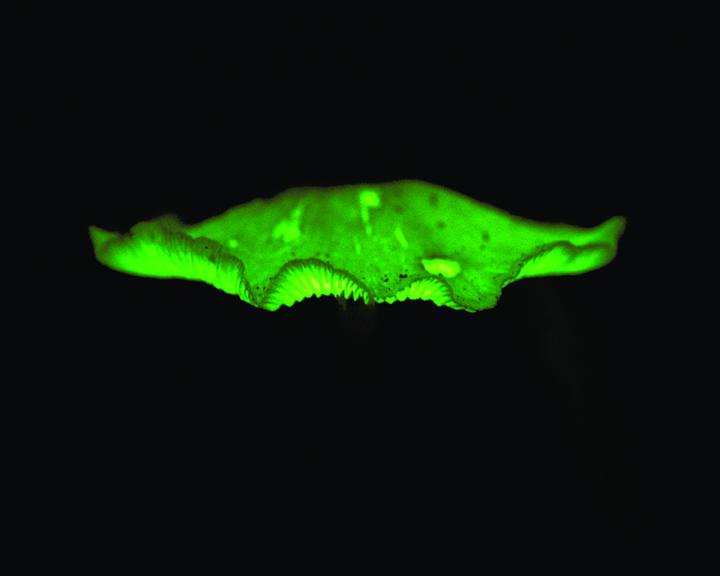

On a flashlight-less night walk in the Monteverde Cloud Forest in Costa Rica, Perlman saw a small singular patch of light on the ground, obscured by a leaf. Underneath, he discovered a mysterious, phosphorescent mushroom, which he photographed with a 20-minute exposure.

page 7 of 10

|

Pseudomyrmex ants are fiercely territorial and protective of their habitat —— in this case, the branch of an acacia tree. Nubby yellow structures called Beltian bodies, located at the tips of the leaves, offer ants a complete diet, eliminating the need to dine out. The acacia, on the other hand, struggles to grow the leaves that provide the Beltian bodies to its ants year-round, especially during the dry season, when most other plants are dropping leaves. In this tidy mutualism —— a biological relationship in which two different species benefit from each other —— the ants enjoy a steady source of nourishment; in return, they protect their turf, keeping insects from eating the acacia’s leaves.

page 8 of 10

|

From South America to Texas, male leafcutter ants grow up, as the males of so many species seem to do, just eating and hanging out. Then, during one single day of utter sexual abandon, the virgin queen ant mates with up to 20 lucky males —— well, perhaps not so lucky, since they perish afterward. Loaded up with 300 million sperm, the queen now has the wherewithal to reproduce millions of female worker ants in a new colony. To feed the legions of larvae the queen will produce over her lifetime, the colony cultivates a fluffy white fungus —— essentially a “starter” that is continually fed chewed-up leaves by worker ants. In a neat mutualism, the fungus keeps the colony alive, and the colony keeps producing the fungus. Only the bare, naked plants are the “hapless suckers” in this triangle, says Perlman.

page 9 of 10

|

Yellowstone National Park is sitting on a supervolcano that experts estimate could bury one-third of the continental United States in ash if it erupted. Though the last eruption occurred 600,000 years ago, magma deep in the earth continues to heat pools like this one, sometimes to the boiling point. The pool’s center is clear blue because nothing can live in its superhot temperature. But the yellow and brown surrounding rings represent different species of heat-loving ancient bacteria known as Archaea, each color group surviving in a specific temperature zone.

page 10 of 10

Biologizing in Your Backyard

|

To photograph this trillium in Cold Spring Park in nearby Newton, Mass., Perlman set his camera on the ground with its super-wide fish-eye lens pointing up. The resulting image makes this spring ephemeral look anything but fleeting. Only a half-dozen inches tall, trillium muscles its way out of the ground and blooms in early April during that short-lived period when trees are still leafless and dormant, the forest is still cold and the sun is still weak, but the winds are warm.