Reading God’s Mind

Photo by Katherine Lambert

Edward Dolnick '74

Daring, eccentric and often solitary, Sir Isaac Newton and his contemporaries were God-fearing men who solemnly believed that demons walked the earth and divine wrath rained down with every illness, fire and comet. Yet these original “mad scientists” transcended the blackness of 17th-century superstition and turned up the lights on our modern understanding of the universe. Here, author Edward Dolnick ’74 talks with Brandeis Magazine’s Theresa Pease about his popular book “The Clockwork Universe: Isaac Newton, the Royal Society and the Birth of the Modern World,” published by HarperCollins in 2011.

You majored in math at Brandeis and ended up being a writer. How so?

I was astonishingly slow to catch on to my own life. For me, romantic boyhood connotations about the life of the mind always centered on science and discovery, so I set out to be a mathematician. I spent a lot of time thinking about infinity. It thrilled me to arrive at Brandeis and find classrooms full of other people who were also excited about ideas.

By the time graduation came, I’d taken a lot of English courses and liked them. Plus I came to think that, as much as I loved these highfalutin math courses, I’d never be more than a so-so math professor. So I brashly presented myself to The Boston Globe as a science writer. I really liked covering the medical and university science community, but when my wife [Lynn Golden Dolnick ’74] was offered her dream job three years later as a biologist at the National Zoo, we moved to Washington, D.C. I began freelancing, first for newspapers and later for magazines.

You ventured into book writing in the 1990s, yet you didn’t choose math topics until you’d already published five other volumes. Why is that?

I had set aside my old interest because I feared math was too strange, dull and esoteric for most readers. I kept it as my secret shame! So my first book, “Madness on the Couch,” was an anti-Freud treatise, a combination of science and history. My second, “Down the Great Unknown,” told of an ill-fated 1869 journey through the Grand Canyon. Then came “The Rescue Artist” and “The Forger’s Spell,” two sort of mysterious and amusing stories about art history.

As the years went on, though, I realized that science had become more generally appealing. Suddenly, people liked to read about cool things like black holes. They always knew names like Galileo and Newton — but they had very little idea about what these guys did, really.

Online reviews for “The Clockwork Universe” hover around 4.5 stars out of 5, and many of the most effusive come from readers who express little interest in science and math. Yet you seem to capture their interest.

The book tries to weave together a few threads. One is straight history: What was it like to be alive in the 1600s, to witness the great London fire of 1666 and the bubonic plague? What did things look like? What smells filled the air? I tried to bring these colorful times and characters to life by providing lots of sensual detail. At the same time, I tried to offer up clear explanations of things like gravity and calculus.

You use strong, vivid imagery. You don’t say merely that Newton and Gottfried Leibniz were rivals who simultaneously unraveled the mysteries of calculus, but that they were “intellectual titans grappling like mud wrestlers.” On the sanitary conditions of the day, you don’t just describe the filth and odors, but point out that, in Paris, an edict was passed calling for the glittering corridors of the Palace of Versailles to be “cleaned of feces once a week.” You quote a contemporary who describes the decaying bodies of plague victims piled “like cheese between layers of lasagna.” And, as for Newton himself, you don’t merely say he was strange, but note that he died a virgin at age 84 and that he “teetered always on the brink of madness.”

Newton surprised me. As a science reporter, I had met lots of brilliant people, and I started the project thinking he was like today’s geniuses. But it turned out Newton was not “just like them” with the treble turned up a bit. He wasn’t merely some prickly guy who happened to be born at the right time in history; he was truly the oddest duck ever. Even his contemporaries didn’t know what to make of him, and they literally believed he had some kind of magical powers. Newton himself — like Mozart in “Amadeus” — actually thought he’d been touched by God and could do things no one else could do. Nowadays no one would dare to think such a thing; it would sound too crazy.

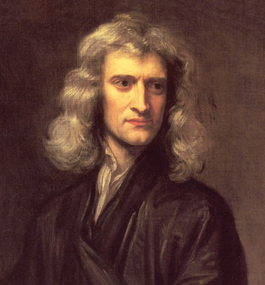

Awkward and asocial, Sir Isaac Newton (shown in a 1689 painting by Godfrey Kneller) thought he’d been magically designated by God to reveal the universe’s secrets. His contemporaries thought so, too.

page 2 of 2

You refer to members of the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, the world’s first-known scientific organization, as being like “very smart, very reckless Cub Scouts” and describe meetings where they sat in powdered wigs watching a baby chick suffocate in a newly invented vacuum jar and witnessing blood transfusions from sheep to humans. You talk of scientists who treated cataracts by blowing dried human excrement into a patient’s eyes, flashy public executions of the goriest sort, and doctors whose “cures” would probably kill you even if the bubonic plague did not. So, yes, a measure of craziness comes through.

The point is that the men who made the scientific revolution were not time-travelers who were just like us but who happened to live a long time ago. They were people who were half-medieval and half-modern, and that kind of strange hybrid is what makes for the fascination. On the one hand, they really did believe in ghosts and devils — they interpreted comets as terrible omens, were poised to witness the end of the world at any moment, and saw God’s wrath in almost everything. And yet somehow these same people laid the foundation for our modern understanding of the universe. How they held both those sets of ideas in their heads at the same time is what makes the story so compelling.

You mentioned that even the great Johannes Kepler made his living casting horoscopes.

That was what you had to do. There was no job or even word for a “scientist.” No one would pay someone to stare through a telescope. But if you could forecast whether your side would win the next war, that was worth paying for. So if you were an astronomer, you would bill yourself as an astrologer, and that way you could earn your keep.

|

Given the fear and superstition, what in the 17th century made it possible for us to move from the dark into the light quite suddenly? Was that a coincidence that all these people — Galileo, Newton, Kepler, Leibniz and others — converged within a few decades, or was the world just ripe for revealing itself?

It’s a terrific question, and it’s sort of akin to the Founding Fathers in America. Who can explain how Jefferson and Franklin and Washington and Madison just happened to come together at that particular moment in history? What I can explain is why all these things were happening in England. Up until Galileo’s time, the great intellectual vanguard of the day had been in Italy. But Italy was dominated by the Catholic Church, which set itself up against science. Galileo was the genius of the day, yet he spent his lifetime being persecuted by the church.

Then, in 1642, the year Galileo died, Newton was born. England was Protestant at this point, and the dominant notion in England was that religion and science were allies. The English believed the purpose of science was to reveal the grandeur of God’s creation, and so the scientists did not have to skulk around in secret. They were hailed as great figures and prime examples of English insight and intelligence. If you were smart, ambitious and interested in advancing knowledge, England was the center of power.

Newton was a firm believer in God, as you point out, and he scoured the Bible for clues to the secrets of the universe. You argue that he and other 17th-century historians saw themselves as readers of God’s mind — or the solver of several “clues” the deity had laid out for them.

To Newton, studying the world and studying the Bible were the same thing. Newton felt he was honoring the Creator by studying the greatness of his creation. But Newton was so successful in figuring out how the universe worked that, to some people, it seemed to push God aside. If, as some natural historians believed, the universe was a perfect machine, like a clock, then you didn’t need an everlasting God watching over every sparrow that falls. But that was a message that later generations took from Newton’s work; it wasn’t Newton’s message at all.

What kind of responses have you gotten to this book?

Many have come from people who formerly thought science was too hard for them and who enjoyed getting clear explanations of things like gravity and calculus. And there are a lot of people who liked the history and liked reading about the lives of these bizarre geniuses in some kind of context.

I also heard from religious believers who said, “See, our team has the greatest genius of them all. We’ve got Newton!” But then there was also some serious wrestling with this question of science versus religion. It’s still a subject people get agitated about. Is science banishing religion? Is religion true and science false? Are they in conflict with each other? If you believe in one, do you have to do without the other? A lot of people are still struggling with that, and it seems as if they all wanted to share with me their thoughts on the subject.