The Disinclined Page Turner

Courtesy Susan Kusel

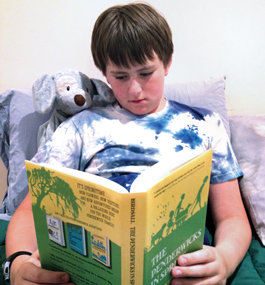

RAPT AT LAST: Kusel's formerly reluctant reader relaxes with a volume from the Penderwicks series.

by Susan Kusel ’98

When people learn that I’m a librarian, they make all sorts of assumptions. My house must be filled with books. I must have started reading to my children as soon as they were born. My kids must be wonderful readers.

The first two assumptions are true. The third is not.

My oldest son, who is 10, enjoyed the years I read picture books to him, but when it was time for him to strike out on his own as an independent reader, he floundered.

He was never interested in the books I thought were wonderful and brilliant. At the library, he checked out nonfiction books about sports, origami or animals, then barely read them. If he had to read a book, he chose something from a commercial series on Star Wars or Pokemon.

“Reluctant reader” is how the book industry labels kids who struggle with reading, kids who are usually boys. I’ve resisted using that label for my son because it puts him in a category I wish he weren’t in. I wish he were like other kids I know, reading at the bus stop, reading at meals, reading at every possible moment. But I know I have to accept that reading isn’t his favorite activity. And I have to be OK with that.

As a librarian and a bookseller, I’ve watched a certain dance unfold in the aisles more times than I can count. Parent and child come in together. The parent requests a book she knows from her childhood, such as a Nancy Drew or “Charlotte’s Web.” I pull it from the shelves. The child’s face falls as she looks at the front and back covers. The child pulls from the shelves a book she wants to read — a graphic novel or something about Calvin and Hobbes. The adult isn’t familiar with the book or it looks overly commercial, and her face falls.

Which book do they walk away with? That part of the dance changes each time. But I can tell you that when it is the child’s choice, the child’s nose is in it by the time the exit door is reached. Now, do I believe that kids should read only commercial books? As with all things in life, there needs to be a balance. A plateful of broccoli can be difficult to get down, but if we add a helping of potato chips from time to time, the broccoli goes down a lot easier.

In my work, I see parents who are overwhelmed because they are not aware of how much the field of children’s books has changed. They don’t know what’s out there, or they may be reading a book appropriate for a 5-year-old to a 2-year-old. So the next time you’re in a library or an independent bookstore, ask for advice. You’ll learn what is both first-rate and popular today in all categories of books and at every reading level. When you choose a book for a child, you need to accomplish two things. You need to find a book that both you and the child have a comfort level with. And you need to find a book the child will actually read.

It’s also important to relax. Several years ago, I spoke at a local hospital to a group of postpartum mothers to recommend a few board books they could use with their very young babies. I’ll never forget one exhausted mother who looked at me, panicked. Her son was already 6 weeks old, she said — she hadn’t started reading any of the books on my list to him. Would he still be OK? I assured her he would be fine.

There’s no prescribed magic list of books, no perfect way to do things. All any of us can do as parents is to try our best, and mix some broccoli in with the potato chips.

Recently, I had the great honor of serving on the Randolph Caldecott Medal selection committee. This award has been given since 1938 to classic picture books such as “Make Way for Ducklings” and “Where the Wild Things Are.” I was one of the 15 librarians and book experts who decided this year’s gold medalist.

Despite his lack of interest in reading, this was something my son got really excited about. He helped me unpack boxes of submissions as they arrived and scan each book into a database. One picture book, out of the hundreds covering my shelves, became his favorite, and he sat next to me for hours analyzing its complexities.

At last, the Caldecott Medal winner and the Caldecott Honor books were announced in a huge ballroom in front of more than a thousand people. My whole family came to the press conference to witness the excitement of the moment firsthand. After it was over, librarian friends from all over the country converged to congratulate me. At last I found my son in the crowd. His face was red, and he was in tears, looking as though his dog had just died. His book had lost.

I realized I nearly categorized my son too soon. Or perhaps there was no easy category to put him into. My supposedly reluctant reader was so in love with a book that he was in mourning for it. This connection, what I had wanted for him all along, was achieved when I had least expected it.

Every night during my childhood, no matter how tired she was, my mother sat on the floor in my brother’s bedroom to read books to him and me. We didn’t have a bookcase. Our picture books, mostly obtained from library book sales, sat on a small shelf in my brother’s closet. Though I certainly remember some of the books we read, what I remember the most is the special time we had with our mother every night.

And so, no matter how tired I am, I try my best to sit down with my children at the end of each day. I have a special reading chair. I have thousands of books. Many are autographed to my kids or are first editions, and many others come from library book sales. We read silly books, wonderful books, an occasional commercial book, books that haven’t won a Caldecott Medal and books that have.

That time that we have with one another every night? I wouldn’t trade it for anything.

Susan Kusel is a librarian, a children’s book buyer and selector at an independent bookstore, and a children’s literature consultant.