The Mystical Power of the Hebrew Letter

Courtesy Edna Miron-Wapner

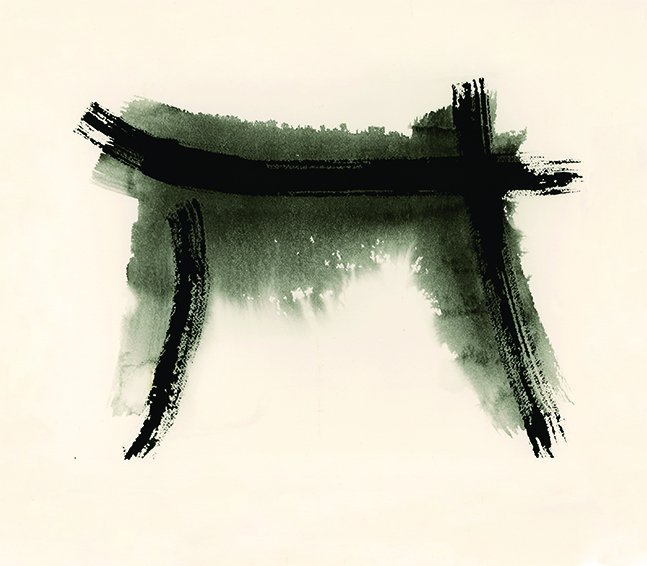

THROUGH A ZEN LENS: A rendering of “he,” the fifth letter of the Hebrew alphabet, by contemporary artist Edna Miron-Wapner, using sumi ink made from the soot of burnt oils, a traditional medium in Japanese calligraphy.

by Lawrence Goodman

“A truly beautiful letter,” writes Izzy Pludwinski in his book “The Beauty of the Hebrew Letter” (Brandeis University Press, 2023), “will possess a dynamism, an internal lifeforce.”

The book demonstrates the ever-changing beauty of Hebrew letters and writing through an examination of historical documents, artwork, typefaces, religious texts, and even graffiti.

“Good, strong calligraphy is like music,” Pludwinski explains. “It has a rhythm and flow all its own. It goes beyond the letters to express something abstract and deeply emotional.”

An Israeli artist, Pludwinski fell in love with Hebrew writing in the late 1970s after he saw a poster in a New York City synagogue advising worshipers that a single missing letter in a Torah scroll could undercut the sanctity of the entire scroll.

“What mystical power could a single letter have?” he wondered.

Hebrew, which is read from right to left, likely originated sometime during the middle of the second millennium B.C.E., written and spoken by the Israelite tribes who settled in Canaan.

When the Babylonians conquered ancient Judah in the 6th century B.C.E., sending many Israelites into exile, Hebrew gradually ceased to be spoken. It became primarily a written language, used in liturgy, rabbinical commentaries, and books of the Hebrew Bible.

It was only during the 19th century, with the rise of Zionism, that Modern Hebrew emerged and became widely used by the Jews who settled in Israel.

Pludwinski’s book surveys a wide range of writing samples, including an inscription on a stela, dated around 840 B.C.E.; Sephardic script in the Prato Haggadah, from 14th-century Spain; the cover of a 1920s literary magazine dedicated to exploring Yiddish expressionist writing and art; and the work of contemporary Israeli artist Edna Miron-Wapner, who combines her interest in Jewish mysticism with her love for Japanese Zen art.

“Letters are the potential energies through which the universe was created,” Pludwinski says.