Object Lessons

In which Brandeis is revealed to be much greater than the sum of its parts.

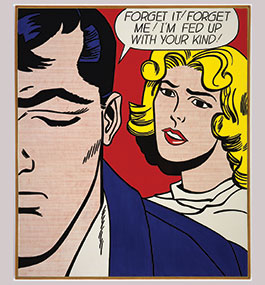

Roy Lichtenstein, “Forget It! Forget Me!” 1962. Magna and oil on canvas. Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University. Gevirtz–Mnuchin Purchase Fund, 1962.138. Charles Mayer Photography. Image courtesy Rose Art Museum.

by Sarah Church Baldwin

The visual history of Brandeis is large; it contains multitudes.

But even a small sampling of items yields a magnificent portrait. Go back in time with this handful of objects that invoke iconic milestones and memories from Brandeis’ first 75 years.

Pop Goes the Art

From the outset of his presidency, Abram Sachar, H’68, wanted Brandeis to have an art museum. In 1958, a Brandeis trustee and his spouse pledged the funds to construct one. The Bertha and Edward Rose Art Museum, named for its founding donors, was dedicated in 1961. Samuel Hunter, former curator of painting at the Museum of Modern Art, was its first director.

In 1962, New York art collector Leon Mnuchin gave the Rose $50,000 to use as seed money for a contemporary art collection. Hunter; Mnuchin; and Robert Scull, a prominent Pop Art collector, began prowling New York galleries, spending no more than $5,000 on any individual artwork. With a discerning eye, Hunter turned the young Rose into a contemporary-art powerhouse by acquiring early and important works by Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg, and Andy Warhol, as well as this piece — “Forget It! Forget Me!” (1962) — by Roy Lichtenstein.

page 2 of 20

The Great Pivot

Brandeis focused on staying resilient, creative, safe, and connected during the earliest days of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Faculty modified syllabuses and teaching methods. “Hybrid” became a household word. A special task force, website, and dashboard kept the community abreast of all things COVID-related. Branded masks were distributed by the thousands. Lawn circles, Plexiglas barriers, and tents popped up around campus. Tens of thousands of COVID tests were administered.

The all-hands-on-deck approach meant almost 2,000 students were able to return to campus by the fall 2020 semester.

Meanwhile, faculty experts across the disciplines were applying their know-how to decoding the mysteries of the virus, devising treatments, and improving public-health responses. Alumni joined the fight as health-care workers, first responders, scientists, policymakers, and activists.

And in a providential twist, the pioneering messenger RNA research of Drew Weissman ’81, GSAS MA’81, P’15, H’23, was used to develop effective COVID-19 vaccines, which continue to keep millions of people around the world safe from a highly contagious novel virus.

page 3 of 20

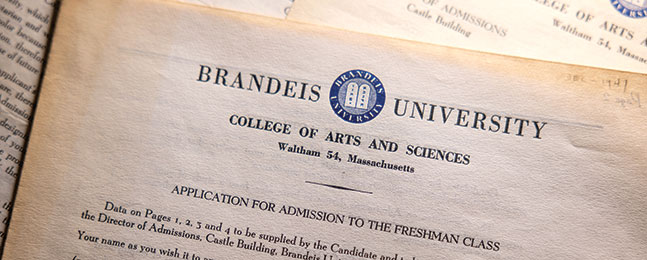

First Class Application

In 1947, students applying to be part of Brandeis’ inaugural class were asked to state their marital status, parents’ occupations, jobs held, and military service completed. They identified their favorite extracurricular activities, choosing from a list that included “Boy Scouts,” “year book,” “needlework,” and “poultry.” They were reminded to “give adequate thought” to their written response to this question: “What sort of person are you?”

What’s most notable is what’s not on this application. Unlike many U.S. colleges, which followed subtly or openly antisemitic admissions policies, Brandeis did not inquire about an applicant’s religious affiliation. Although the university was founded by and for the Jewish community, from Day One it was a place open to all.

page 4 of 20

Notes on a Virtuoso

Composer, conductor, pianist, and force of nature, Leonard Bernstein, H’59 (1918-90), forever changed the way the world hears music. An early Brandeis supporter, he taught at the university from 1951-56; chaired the nascent School of the Creative Arts; and, in 1952, conceived and directed the inaugural Festival of the Creative Arts (which now bears his name) to celebrate Brandeis’ first Commencement. Bernstein is often pictured dressed in a tuxedo at a grand piano, but his introduction to the instrument was on a much humbler scale. Growing up in Lawrence, Massachusetts, he developed his musical genius on a rather dowdy dark-brown upright, left at his family’s house by an aunt. That piano, gifted to Brandeis in 2002, now resides in the Slosberg Music Center lobby.

page 5 of 20

Master Planner

The clean, functional modernist style that characterizes the Brandeis campus is a far cry from the farm structures and small, oddly shaped buildings the founders inherited when they acquired Middlesex University in 1946.

The “young university in a hurry,” as it was referred to in a 1961 Saturday Review article, needed buildings to house its fast-expanding student body and academic programming. Finnish father-and-son team Eliel and Eero Saarinen, who produced the university’s first master plan, designed Ridgewood Quad, Sherman Hall, and Shapiro Residence Hall.

But Brandeis really owes its look to architect Max Abramovitz, who, starting in the mid-1950s, oversaw campus planning for 30 years. His architectural drawings (one of which is shown here) depict the outlines of the modern campus. Abramovitz went on to design many of the university’s buildings, including the Rose Art Museum, the Slosberg Music Center, and the award-winning trio of chapels.

page 6 of 20

If the Hat Fits

In America, many universities are named for their founder. Brandeis was named for an inspiration.

Louis Dembitz Brandeis (1856-1941) — whose derby hat resides in the university’s Archives and Special Collections department — was the first Jewish justice on the U.S. Supreme Court and one of America’s greatest legal minds. In founding Brandeis University, the American Jewish community sought to build an institution that put into practice the universal principles Justice Brandeis embodied: open and robust inquiry, a passion for education, and a commitment to being of service to others.

page 7 of 20

A Haven for the Humanities

This Palestinian bag jar — a vessel used from the 1st through the 7th century C.E. to carry olive oil and wine — is part of Brandeis’ Classical Studies Artifact Research Collection, which includes more than 800 artifacts from ancient Mediterranean civilizations. The collection serves as an invaluable research resource for undergraduate and graduate students, allowing them to engage directly with antiquities, and deepening their understanding of the humanities as both age-old and evolving.

page 8 of 20

Make It So

Founded in 2014, Brandeis’ MakerLab was one of the first makerspaces to open at a liberal arts university. Working in the MakerLab, students in the Prosthesis Club made this 3D-printed hand, designed to be used by a child without a functioning limb. You don’t have to be an engineer or even a techie to join the Brandeis maker community. Custom 3D scanners and printers, virtual reality gear, robots, and much more invite all students to dream, innovate, and create.

Twentieth-century Judeo-Persian copper plates, part of the Bernice and Henry Tumen Collection, donated to Brandeis in 1981.

page 9 of 20

By the Light of Reason

Brandeis was conceived of as a gift from American Jewry, at a time when Jews and others faced discrimination in higher education. Though secular, the university would embody the search for truth, the reverence for learning, and the sense of duty to improve the world that define Jewish tradition.

Today, Brandeis scholars share knowledge about Israel and the Middle East. They work to fight antisemitism. They advance the field of Jewish educational scholarship and the study of contemporary Jewish life. They investigate the history, religion, and culture of the ancient Near East, and Jewish, Arabic, and Islamic civilizations.

They do so by engaging with Jews and non-Jews alike.

page 10 of 20

Building Blocks of Justice

In 1969, Ford Hall was occupied by 70 Black students and allies in an 11-day protest that paved the way for the creation of an African and African American studies major, and other advances in diversity, equity, and inclusion at Brandeis.

Ford Hall was torn down in August 2000, but this brick from its structure is more than a memento. Forty-six years after the 1969 occupation, students organized #FordHall2015, a 13-day sit-in that resulted in the university’s vow to reaffirm and accelerate Brandeis’ founding values, including a quest for ethnic and religious pluralism, and a commitment to equitable social change. In 2021, the university introduced revised Anti-Racism Plans. In this and other ways, Brandeis continues to assess how institutionalized racism has affected the university historically and how it can be addressed today.

page 11 of 20

A Throne To Throw Up In

In the basement of the Rabb Graduate Center, a massive motorized chair tests how humans react to changes in motion and orientation. The custom-built Multi-Axis Rotation System device rotates along the same axes as an airplane. It’s useful for evaluating a person’s perception of the gravitational vertical at extreme body orientations — in other words, it tests whether you would know which end is up if you were spinning through the sky in an F-15 Eagle. It also measures how the human body orients itself in zero gravity.

The chair is part of the Ashton Graybiel Spatial Orientation Laboratory, one of only two labs in the U.S. capable of investigating sensory motor adaptation, motion sickness, and the effects of various force environments on the body. The lab, which opened in 1982, contains more than 20 major pieces of equipment, including a 22-foot-diameter rotating room, the only U.S. facility that can create artificial gravity.

page 12 of 20

Rainbow Over Brandeis

Homosexuality is a civil rights concern, affirmed a 1957 article in The Justice. Over the coming decades, Brandeis students kept up a steady drumbeat of advocacy on matters of sexual orientation, gender, and identity. A student group known as the Brandeis Gay Advocates came on the scene in 1975, followed seven years later by the still-active group Triskelion. Activism took the form of protests, proposals, and marches. During Coming Out Week in 2002, a 25-foot condom was erected on campus to raise awareness for AIDS.

Still, the road to inclusivity wasn’t without potholes. Trisk posters were repeatedly torn down in the 1980s and ’90s, and the group’s office was vandalized more than once.

Over time, LGBTQ folks and their allies received increasingly formalized recognition and support. Queer Pride Week became Pride Month in the late ’90s, a nondiscrimination policy for “gender expression and identity” was adopted in the early 2000s, and in 2012 Brandeis celebrated LGBTQ students at its first Lavender Graduation.

page 13 of 20

The Greening of Brandeis

In 2018, the university opened the state-of-the-art Skyline Residence Hall, one of the most energy-efficient buildings on campus and one of the greenest dorms in the Boston area. Four years later, the university kicked off its Year of Climate Action, designed to deepen Brandeisians’ understanding of climate change as a social justice issue. University officials have also launched a study that will inform a Decarbonization Action Plan, transforming energy use on campus, reducing emissions, and setting Brandeis on a path to carbon neutrality.

page 14 of 20

The Real Thing

Herbert Marcuse (1898-1979) was a legendary German philosopher and social critic who, after fleeing the Nazis, settled in the United States in 1934. From 1954-65, he taught politics and philosophy at Brandeis, inspiring many followers of the New Left, including activist Angela Davis ’65.

In 2014, a Brandeis librarian was dutifully sifting through the Goldfarb archives in search of items to commemorate the 50th anniversary of “One-Dimensional Man,” Marcuse’s classic critique of modern capitalism and communism, published in 1964. After pulling out a pair of black notebooks, he realized he’d hit the jackpot.

Neatly tied inside the notebooks was an early manuscript of “One-Dimensional Man.” The many cross-outs, carets, and additions show how Marcuse’s ideas were evolving as he wrote. And they would continue to evolve. Compared to the Brandeis manuscript, the published text is an even harsher condemnation of the soul-destroying aspects of technology-driven Western culture.

Jonas Ekstromer / AFP / Getty Images and Alexander Mahmoud / © Nobel Media AB

Michael Rosbash (in left photo, at left) and Jeffrey Hall (right photo) receive their Nobel medals in Stockholm.

page 15 of 20

Heavy Medal

The Nobel Prize medallion is made of 18-carat gold, measures 2.6 inches in diameter, and weighs about a third of a pound. Michael Rosbash, the Peter Gruber Endowed Chair in Neuroscience, and Jeffrey Hall, professor emeritus of biology, were each handed one in October 2017.

Along with Michael Young of The Rockefeller University, Rosbash and Hall received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their breakthroughs in understanding the molecular mechanisms that control circadian rhythms, the inner biological clock that regulates almost all life on the planet, from humans to fungi.

A device Rosbash and Hall built in the 1980s while doing their award-winning research at Brandeis is now housed at the Nobel Prize Museum, in Stockholm. Their homemade fruit-fly activity monitor allowed them to compare — simply yet effectively — the sleep habits of normal and genetically mutated fruit flies.

page 16 of 20

Opening Doors

Founded in 1968, the Myra Kraft Transitional Year Program embodies Brandeis’ commitment to repairing the world.

Originally called the Transitional Year Program (then renamed for philanthropist Myra H. Kraft ’64, the late wife of New England Patriots owner Robert Kraft), MKTYP prepares talented students from under-resourced high schools for a competitive college-level liberal arts curriculum through a combination of small classes, rigorous academics, and strong academic support.

Over the years, the program has graduated more than 1,000 alumni.

It is the oldest continuous program of its kind in the United States.

page 17 of 20

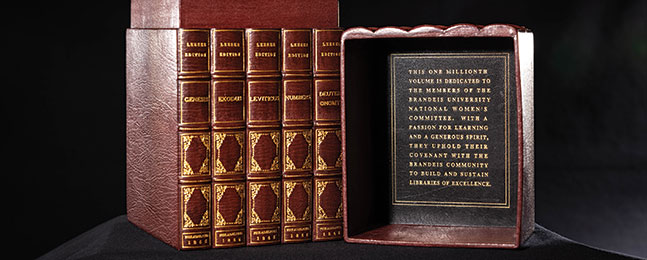

A Gift of Biblical Proportions

By the time Brandeis opened its first library in 1948 — in a converted horse stable — eight women had already organized a small army of volunteers to raise funds for its operation. The Brandeis University National Women’s Committee was eager to ensure the Jewish-sponsored nonsectarian university’s library would be first-rate. Now known as the Brandeis National Committee, it has become one of the largest library-friends groups in the world.

In 1996, the BNC gave the university this copy of Isaac Leeser’s 1845 translation of the “Five Books of Moses, Torat ha-Elohim/The Law of God,” the first Jewish translation of the Bible in the United States. It was the one-millionth book added to the Brandeis Libraries collection.

page 18 of 20

All the Single Ladies

Though universal on college campuses in the 1950s and ’60s, the rules governing socializing between the sexes in dorms — known as “parietals,” from the Latin word for “wall” — have gone the way of the typewriter.

Yet parietals were firmly in place during Brandeis’ first decades. Socializing between men and women in dorms was limited to a few hours daily in the common rooms of Smith Hall, Founders Hall, and the Ridgewood Cottages. Smoking, on the other hand, was permitted almost everywhere on campus.

By the early ’60s, men and women were allowed to visit each other in their residence-hall rooms. That victory was partially rolled back in March 1964 when President Sachar “decreed that henceforth, when students entertained members of the opposite sex in their rooms, the doors must be ajar,” as The Justice reported. Students responded by organizing a strike that canceled classes for several days.

Time marched on. By 1991, the annual Screw Your Roommate dance was encouraging students to arrange blind dates for their roommates.

Today, Brandeis allows men and women to share floors, rooms, bathrooms, and beds. Couples can room together. Most campus housing is gender-neutral. Single-sex dorms have given way to a few scattered single-sex floors. And smoking is prohibited everywhere.

page 19 of 20

The (Science) Universe Expands

Brandeis is undertaking the next steps in the revitalization of its scientific enterprise that began more than a decade ago with the construction of the Shapiro Science Center, which opened in 2009.

The current stage of the revitalization project is known as Science 2A. It will include the construction of a four-story, ADA-compliant building adjacent to the Shapiro Science Center, adding up to 100,000 square feet of new and renovated space for state-of-the-art wet labs, core facilities, and learning spaces. In addition, a new interdepartmental engineering major and program, recently approved by a faculty vote, will draw on all aspects of the liberal arts.

An unequivocal assertion of Brandeis’ commitment to the sciences, Science 2A will bolster recruitment and retention of top faculty and students, strengthen the university’s leadership in science, and allow faculty and students to expand their research activities and connect across disciplines.

page 20 of 20

You’ve Come a Long Way, Baby

Over the years, countless admissions volunteers have worn pins like these as they explained the benefits of a Brandeis education on campus tours.

The numbers prove how successfully they do their job. With more than 1,000 students, the Class of 2027 is 10 times the size of the Class of 1952. The current student body comes from around the globe, hailing from 39 U.S. states and 29 countries. One-third are students of color, and almost a fifth are first-generation college students. Twenty percent of the student body are international students, who speak a total of 55 languages.

Sarah Church Baldwin is a freelance writer living in Pawtucket, Rhode Island.