Senior Statesman of Health Care

Photo by Mike Lovett

Stuart Altman, a senior member of the Schneider Institutes for Health Policy at the Heller School, has been immersed in health care reform for decades.

by Jeffrey Krasner ’80

In June 1974, Stuart Altman, Sol C. Chaikin Professor of National Health Policy at Brandeis’ Heller School for Social Policy and Management, was President Richard Nixon’s top health care official. As deputy assistant secretary for planning and evaluation at the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, Altman was trying to forge a compromise that would extend health coverage to all Americans.

But given Washington’s polarized political environment, he had to resort to tactics from a cheap spy thriller. Nixon’s man couldn’t be seen meeting with someone from the office of Senator Ted Kennedy, the Massachusetts liberal championing universal coverage. Nor could Kennedy’s aide be seen conversing with someone representing Congressman Wilbur Mills, a conservative Democrat from Arkansas and chair of the all-powerful House Ways and Means Committee, which had jurisdiction over health care.

So, in late afternoons, Altman would look both ways to make sure he wouldn’t be recognized before stepping out of a cab and descending the steps into the basement pub at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church on Capitol Hill. There, all three sides would meet to hash out a health-coverage compromise.

Despite the cloak-and-dagger tactics, the effort failed. Kennedy and Nixon couldn’t agree on the terms of a mandate that would require workers to buy coverage from private insurers. A separate effort under President Gerald Ford fell apart after Mills was famously discovered in his car with a stripper named Fannie Fox, an event that sapped Mills of political clout and credibility.

For Altman, it was a full-immersion initiation into the capricious and often brutal politics of health care reform — a struggle that has been the centerpiece of his career. Altman recalls the secret church meetings and other twists in his new book, “Power, Politics and Universal Health Care: The Inside Story of a Century-Long Battle” (Prometheus Books, 2011), co-written with David Shactman, a former senior fellow at the Heller School and Altman’s longtime collaborator.

According to Altman, efforts to extend health coverage to all Americans have always been fraught with partisan politics, powerful business interests intent on killing reform, and strange twists of fate. For 40 years, Altman has had a front-row seat at the show. After serving Nixon, Altman headed the Prospective Payment Assessment Commission — the overseer of Medicare payments to hospitals — for 12 years. In 1991, he advised president-elect Bill Clinton on his plan to overhaul the health care system. Most recently, he was a member of the health-policy team during Barack Obama’s first presidential campaign.

But Altman, 74, never set out to work in health care.

“It was all a fluke,” he says. It began in the early 1960s when the New York City native was pursuing a doctorate in labor economics at the University of California, Los Angeles. For his dissertation, he chose to write about unemployed married women, who were becoming a larger force in the labor market. An official for the Federal Reserve invited Altman to spend a year at the central bank doing his research, which the Fed supported. From there, Altman was recruited by the defense department, which was seeking labor economists to study an effort to create an all-volunteer military.

“Going to the Pentagon was a culture shock beyond belief for a kid from the Bronx who had flunked out of Boy Scouts,” says Altman, who’d had no exposure to any sort of military culture.

Nor did he feel comfortable there. He left government to teach at Brown University in 1966. But soon after, he got a call from a former Pentagon colleague asking him to help on additional research. And a few years later, he was working at the Urban Institute in Washington investigating an anticipated shortage of nurses. After that, he became deputy assistant secretary of health.

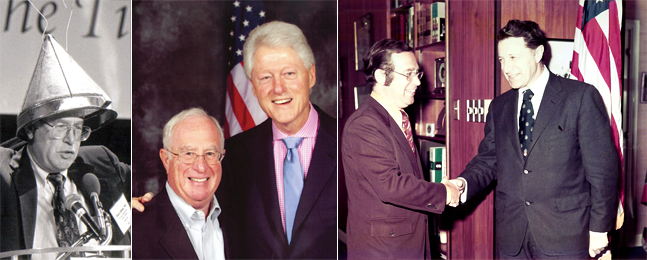

From left: Altman pokes fun at “instant experts” at a Washington meeting; poses with President Bill Clinton in 2010, and greets Health, Education and Welfare Secretary Caspar Weinberger in the early 1970s.

page 2 of 2

“The truth is, I knew very little about health care,” says Altman, “but I’d been writing this book about nursing, so I had a very, very thin veneer of knowledge.” With a political squabble holding up the confirmation of Nixon’s chosen head of health policy, Altman became the highest-ranking health-policy official in the Nixon administration.

Barely remembered amid today’s ruthless battles over President Obama’s Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 is the fact that Nixon championed a broad array of health care advances, starting with his effort to create universal coverage — the reason for the clandestine church meetings. “It was one of the two or three most productive periods of federal involvement in health care ever,” Altman says. “Nixon should be remembered as a health care president.”

In his book, Altman, who joined Brandeis in 1977, traces the century-old effort to create a universal health care system in the United States. The backroom deals, high-stakes negotiations and historical accidents that left this country as the last industrialized nation without universal health care are lucidly laid out. The historical parallels are often uncanny. In 1974, during his negotiations with Republicans, Senator Ted Kennedy was viciously attacked by union leaders and other Democrats for abandoning the fight for a single-payer health care system (one in which the government, instead of private insurance companies, pays the bills). President Obama made the same compromise in 2009 in his efforts to pass the ACA and drew similar attacks from liberal Democrats.

Along the way, Altman grew from young policy stand-in to senior statesman of health care, with a range of experience in government and academia that is unmatched.

“Nobody more than Stuart can credibly claim to have been at the forefront of health-policy development over the last 40 years, from Nixon all the way to Obama,” says Chris Jennings, the senior health care adviser to President Clinton from 1993 to 2001. “He excels not only in his longevity but in his relevance. Now he’s involved in trying to complete the unfinished chapter in Massachusetts health care reform — constraining cost growth.”

Altman, who describes himself as a moderate, says he is concerned about the future of the ACA, which Republicans have vowed to repeal or dismantle. A key provision of the law, an individual mandate requiring citizens to purchase health insurance, will be reviewed by the Supreme Court, which is expected to issue a ruling in June.

“Though most legal scholars believe the individual mandate is constitutional, I can’t rule out the possibility that the court will find it unconstitutional,” says Altman. “Nevertheless, the ACA is not socialized medicine. Quite the opposite. It’s designed to shore up private insurance. And I think it’s going to be very hard to totally dismantle the ACA, even if the individual mandate is ruled unconstitutional.”

Altman says he’s grateful a graduate dissertation nearly 50 years ago pointed him to a then-arcane field he had never thought to enter.

“There are so many facets to health care, you never get bored — even though many of the issues we’re debating today I’ve been part of once or twice or three times before.”

Jeffrey Krasner leads Watertown, Mass.-based Krasner Health Strategies, which specializes in health care communications.