The Great Persuaders: Debate Team Carries the Argument

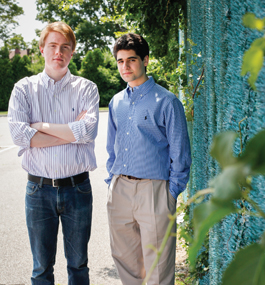

Photo by Jenica Miller

Keith Barry ’13 and Russell Leibowitz ’14

by Susan Piland

Marshal your arguments well, all ye who rise to face them — for they are BADASS.

The members of the Brandeis Academic Debate and Speech Society know how to talk their way out of some pretty tight places.

Competing within the American Parliamentary Debate Association, a circuit of more than 50 top U.S. universities, the Brandeis team ended the 2011-12 academic year ranked number three, surpassed only by Yale and Columbia. Brandeis bested all the other Ivies as well as Stanford, Chicago and many other perennial debating powerhouses.

Unlike debate teams that carefully recruit their participants, BADASS maintains an open-door policy: Anyone who wants to join can.

Members hone their skills and get into fighting trim through countless practice rounds. At practices and in the hard-fought competitions, case topics range widely, from philosophy, to politics, to “Star Wars” (“Yes or no: Should Luke have joined the dark side?”).

A debate round pits two teams of two debaters each against each other. Each team presents its argument in three alternating four- to eight-minute speeches. At the end, a judge decides which team has proved or disproved a case more convincingly.

In addition to achieving its elevated national rank, this year’s Brandeis squad, which boasted more than 20 members, set other top marks:

• The highest-ranked two-person team (Keith Barry ’13 and Russell Leibowitz ’14) in university history; Barry and Leibowitz placed fourth in the nation.

• The qualification of five teams for the national competition (only Yale sent more teams), a university record.

• The most nationally ranked novices on the Novice of the Year board.

• Wins in five tournaments and appearances in the finals of four more, including a win in the Harvard Debating Championships, the largest North American tournament.

• A bid to participate in the Hobart and William Smith Colleges/International Debate Education Association Round Robin, which invites only the top 16 teams in the world.

So, when articulate tacticians duel, what’s the give and take like?

As a brief case in point, Brandeis Magazine asked BADASS stars Barry, of Braintree, Mass., and Leibowitz, of Mount Sinai, N.Y., to square off on a topic.

Here’s the question: Suppose you are in a relationship in which you must choose either to love or to be loved, not both. Which would you choose?

Keith Barry: “It is better to love. To love is not merely a good thing; it’s an absolute good. It’s life-affirming, for love creates a life of meaning. There is a reason people die wishing they had loved more. Do it now. Be content at the end.”

Russell Leibowitz: “It is better to be loved. Loving may be valuable; rejection is not. Imagine knowing your love will never be reciprocated. Rejection corrodes the human spirit. We can only appreciate ourselves when we’re loved. That’s why people turn to religion and God — we need external validation.”

Keith: “The need for validation isn’t nearly as powerful as true love. Love isn’t wanting a random hookup. It’s being willing to lay down your life for another. It’s giving without expecting anything in return. And think about this: If you’re living an ethical life, you would never ask someone to suffer the pain of rejection just to make your life easier. What is easy is not always what is right or most meaningful.”

Russell: “But being loved pushes you to greater heights. Knowing people are dedicated to you is not only a normative good, it leads to self-accountability. Look, there is safety in being loved — in being able to make hard decisions because there is someone to fall back on. There truly is no place like the home you find in the arms of those who love you.”

Keith: “There is no benefit in being loved without loving back. That doesn’t push you to greater heights. It just worthlessly expands your ego. It encourages complacency. To love another is to seek, find and remedy your flaws, to grow and improve. Being loved when we don’t deserve it feels fake and hollow, and inspires a kind of cognitive dissonance.”

Russell: “Regardless of whether the human need for validation ought to exist, the fact is it does. In Keith’s world, you are always miserable, always rejected. In mine, you become aware of your own presence through another’s gaze. It may be true that loving others pushes us to greater limits. But only through being loved do we break those boundaries entirely.”