Mr. Shapiro Goes to Washington

Courtesy U.S. Senate Historical Office

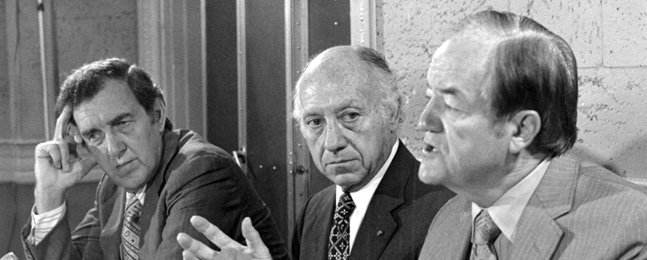

Democrat Edmund Muskie, Republican Jacob Javits and Democrat Hubert Humphrey were among the most significant policymakers in the U.S. Senate during the 1970s.

by John Weingart ’70

I first met Ira Shapiro ’69 on the campaign trail. We were both on the ballot that year, though for different offices, when we bumped into each other canvassing for votes in a dorm in North Quad. He was hoping to represent the junior class on the Student Council while I was seeking one of the sophomore seats. For the record, we both won.

Little did I know then that Ira’s next foray into political life would yield — albeit four decades later — a brilliant, gripping analysis of the ways in which the U.S. Senate has devolved from the highly productive era of the 1960s and ’70s to the politically deadlocked time we live in now.

Acclaim for Ira’s book, “The Last Great Senate: Courage and Statesmanship in Times of Crisis,” has been lavish. The Washington Post, for one, called it “a tour-de-force meditation on the kind of high-powered policymaking and intricate legislative needlepoint that once seemed to define the Senate’s work” and “an extended and lovingly rendered reminder that the U.S. Senate … was once something great.”

Of course, Ira probably could not have written this book without the four-decade detour that placed him in the thick of Capitol Hill goings-on during the heyday of the “last great Senate.”

It all started in 1969 with a simple internship in Washington with Senator Jacob Javits of New York. Supported by a $600 stipend from Brandeis, it seemed a good way to spend the summer between college and Berkeley, where Ira had been accepted to study politics on a National Science Foundation fellowship.

But Washington — and the Senate, in particular — had captured Ira’s soul. So, at the end of his first year at Berkeley, Ira switched to the University of Pennsylvania Law School. After practicing law for a short stint in Chicago, he returned to Washington in 1975 as the legislative legal counsel to Wisconsin’s Democratic senator, Gaylord Nelson.

Over the next 12 years, Ira worked for several Senate committees and other individual members. He had a front-row participant-observer seat to see the men and the few women of the Senate listen to their colleagues with respect, learn from one another, change their minds, compromise and find solutions to national problems. From the same vantage point, he watched it all start to erode.

Although the Senate’s decline as an institution is widely lamented, the power of Ira’s book comes from the extensive and solid research he combines with his own experience to paint rich portraits of many key senators and detailed — even suspenseful — case studies of some of the issues they confronted. He not only documents how far the institution has fallen but also explains the specific events and individuals that caused the changes, offering strategies to improve the present situation.

Ira argues that the senators he knew and respected — Javits, Nelson, Tom Eagleton, a fellow named Joe Biden and many others — were able to work together toward great accomplishments not only because they were capable and committed public servants but because they were operating in a healthy ecosystem.

To cite one example particularly difficult to imagine today, he provides a fascinating account of Republican Howard Baker from Tennessee and Democrat Frank Church from Idaho both reluctantly but eventually actively supporting ratification of the Panama Canal Treaty, despite reasonable certainty that taking this stand would end their political careers.

Some of the sagas the book describes are surprising in other ways. One of the post-Watergate reforms the Senate considered in 1977 proposed the first limit on outside income members could receive from speaking fees. If you knew the political leanings of leading senators in those years, you might expect Ed Muskie from Maine and Robert Byrd from West Virginia to disagree, but perhaps not that Muskie would lead the opposition.

To a colleague on the floor, Muskie responded, “The senator is putting a cap on my income, and he doesn’t give a damn what the consequences are for my family.” Meanwhile, it was Byrd who said, “I don’t think any group of citizens would pay me $2,000 to play my fiddle for 15 minutes if I were a meat cutter or working in a shipyard or practicing law.”

What would it take to return the Senate to an effective and respected institution? In a recent New York Times piece, Ira called for major changes in the Senate rules: restricting the use of the filibuster and dramatically reducing the power of individual senators to obstruct the Senate by placing “holds” on legislation and nominations. But the essential foundation that Ira’s book provides is a vivid reminder that what is needed is not the realization of a perhaps naive, idealistic vision but rather a return to practices we all took for granted not too long ago.

Ira left the Senate in 1988 and entered private law practice, but returned to government during the Clinton administration to help complete the North American Free Trade Agreement. In 1995, President Clinton’s nomination of Ira to the rank of ambassador was unanimously confirmed by the Senate, and, in that capacity, he was involved in negotiating a series of bilateral trade issues with Japan, Canada and Russia.

In 2002, Ira ran for Congress from the Montgomery County, Maryland, district where he lives with his wife, Nancy (Sherman) ’69 (they met in the Rose Art Museum the first day of freshman year). The campaign, described as an “antidote to cynicism,” gained national media attention, and Ira’s experience, positions on issues and sense of humor all received praise. Though the campaign generated even more coverage than The Justice had given our Student Council races, the outcome was not as positive.

Ira has continued to practice international trade law in the Washington office of Greenberg Traurig; Nancy is the associate vice chancellor for academic affairs at the University of Maryland.

“The Last Great Senate” is convincing evidence that, had Ira stuck with his original plan, he would have been a first-rate political scientist (although he might have had to struggle to keep his writing as accessible and compelling as it is here). One can only hope that, with the success of this first book, we will not have to wait so long for the next one.

John Weingart is the associate director of the Eagleton Institute of Politics at Rutgers University.