A Holocaust Heroine Grows Up

By re-examining Anne Frank’s diary, a Brandeis professor invites current students to bear witness to a world gone wrong.

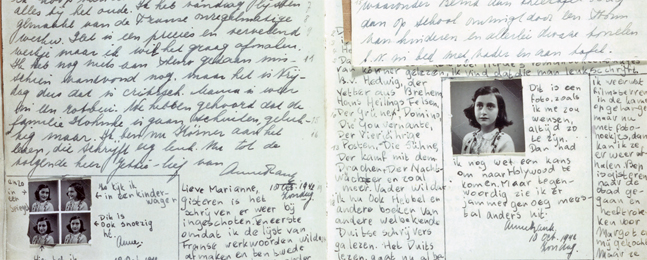

ENDURING LEGACY: Pages from the diary given to Frank on her 13th birthday.

by Jarret Bencks

Anne Frank's diary of her life in hiding during World War II is one of those stories that change as you change.

If you read “The Diary of a Young Girl” as a young teenager, as countless middle-school students do, you relate to Frank’s budding sexuality, her fear of discovery by the Nazis, her feelings of not being understood.

If you reread it as an adult, you take note of her exceptional writing talent, her mature introspection and the book’s lasting power in the crowded field of Holocaust literature.

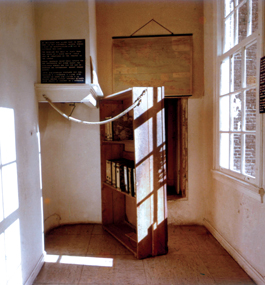

Seventy years after the German Jewish teenager’s death from typhus in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, the outline of her life is etched in the minds of generations of American readers. In 1942, nearly a decade after fleeing Nazi Germany for Amsterdam, Frank, her sister and her parents went into hiding in a concealed apartment above the factory where her father, Otto, worked. The Frank family spent two years in this “Secret Annex” before being captured and sent to concentration camps.

When Otto Frank got out of Auschwitz and returned to Holland in 1945, he didn’t know whether his wife and two daughters were still alive. After he learned of their deaths in Bergen-Belsen, he received three notebooks containing Anne’s diary.

“When he read the diary, he was overcome with the feeling that he hadn’t known his daughter,” says Dawn Skorczewski, English professor and director of university writing at Brandeis. “He was so impressed by her diary; he wanted to show it to the world.”

First published in Holland in 1947, the diary initially made little impact. When it was published in the United States in 1952, however, it quickly became required reading for schoolchildren. Within a few years, Anne Frank’s story was turned into a Broadway play and a Hollywood film, fueling its popularity internationally. Today, the diary has been translated into 67 languages and has sold 30 million copies.

Last semester, Skorczewski offered a course that examined Frank’s iconic status as a Holocaust memoirist and explored how college students engage with a traumatic time that, to them, may seem more like an abstraction than a real chapter in world history.

Supported by the Whiting Foundation, the Theodore and Jane Norman Fund, and the Fulbright Program, “The International Legacy of Anne Frank” was collaboratively taught by Skorczewski and two professors at VU University, in Amsterdam. The class included both American and Dutch students, who were connected through video conferencing and digital exchanges. Each student kept a diary during the course, and entries were periodically posted in a class blog. During the final month of the semester, Skorczewski taught from Amsterdam, and Dienke Hondius, a historian who works at VU and the Anne Frank House, taught from the Brandeis campus.

At the end of the course, two students were selected from both Brandeis and VU to participate in internships at the Anne Frank House, which opened as a museum in 1960 and draws more than a million visitors annually.

This spring, Skorczewski discussed Frank’s legacy, the diary’s changing meaning and the transnational course.

What are some of the diary’s most misunderstood elements?

“The Diary of a Young Girl” is a wonderful narrative that addresses World War II and anti-Semitism, and a beautifully written first-person account of a girl’s development from a somewhat immature child to a thoughtful young adult.

'AN ATTENTIVE WRITER': Twelve-year-old Frank in 1941, the year before she and her family went into hiding.

page 2 of 5

But the book doesn’t really tell you all that much about the acts of genocide we now call the Holocaust. It doesn’t tell you much about what’s going on outside the walls of the house where the Franks hid from the Nazis for two years. It doesn’t tell you about places like the Hollandsche Schouwburg, a theater that became a holding camp, where many Dutch Jews were taken before being sent to concentration camps.

Many children in Europe were in hiding, separated from their parents, without adequate food or access to a radio, all of which Anne had. Many of them were physically or even sexually abused. Anne’s hiding situation was actually a fairly privileged one.

How might a grandparent’s or a parent’s reading of the Anne Frank diary differ from a young person’s today?

When the diary was released in the United States in the 1950s, it was for many Americans the first story about life in Europe during World War II that they had read.

Today, we read it with prior knowledge of the events taking place outside the building where the Franks were hiding, and we know where the Franks ended up. We are saturated with Holocaust stories. We have a better sense of how people in different countries experienced the Holocaust than readers in the 1950s did.

At one time, nearly all young people read the diary. Now, although it is still very popular in the United States, there are many more options. Two Brandeis students surveyed their fellow students for their Anne Frank project. They discovered that more students had read Elie Wiesel’s “Night” than “The Diary of a Young Girl.” Many had also read Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel “Maus.” And almost all our students, in Amsterdam and at Brandeis, had seen “Schindler’s List.”

As a writer, how does Anne speak to young readers?

It’s both her writing style and the content. In the beginning, she’s a child telling her story — she is 13 when her father gives her a diary — and then it becomes more of an adolescent’s story. It’s not just about life during wartime; it’s a look into her mind, how she views others and how she thinks they view her. She talks about her relationship with her parents a lot, and she offers her parents’ lessons on life and love. These are narrative elements children can identify with.

She’s also very gossipy at times, something everyone can relate to. We like to know about people’s lives. And she’s delightfully irreverent.

Are there differences between the way young Americans and young Europeans view Anne’s story?

In Holland, “The Diary of a Young Girl” is not thought of as the introductory Holocaust story, as it often is in the U.S., and some Dutch students have told me they view the Anne Frank House as an American tourist site. Many Dutch people have never visited the house. In fact, our Brandeis interns took the Dutch students on a tour of the house in June. None of them had ever been there before.

HIDDEN AWAY: The original movable bookcase at the Anne Frank House, which concealed the entrance to the Secret Annex.

page 3 of 5

The Dutch consider the diary a children’s book; there is a perception in Holland that it is just a little girl’s diary. Anne’s not that unusual for a typical Dutch girl of the period, some say. Or they’ll say there are other diaries that are just as good.

But Anne’s self-interrogation represents a version of self-scrutiny that many Americans value. It’s probably part of the reason Americans hold the diary in higher regard. The Dutch are more interested in reading about people who try to help one another or who work toward a common good. Americans like stories of self-development.

The Dutch didn’t discuss the war much at all until the 1970s, perhaps because it was too painful to face. Europeans experience the Holocaust differently than Americans do because it happened where they live. Some of their great-grandparents and grandparents fought in the war, and not all on the “right” side. Many died in the war. It is a question of personal memory versus what we think of as the “facts” of history.

So it’s one thing to learn about the Holocaust from thousands of miles away. It is another thing to say, “Someone was taken from the house next to my grandfather’s house and never came back.” Or “I am not sure, but I don’t think my mother’s uncle survived the war. Nobody talks about it.” This explains part of the Dutch people’s reluctance. Trauma is not easy to discuss. My students who are grandchildren of Holocaust survivors have expressed similar sentiments to me.

Has Anne’s story been Americanized at all?

The diary became popular in Europe after it was popular in America. So, in a way, her story was brought to Europe from America and became Americanized in the process. And it is no accident that, since the diary’s initial popularization, Anne Frank has appeared as a character in many American novels.

In both the film and the play, Anne Frank is really an American heroine. In the film, her home looks like a New York City tenement. The annex’s residents hang out the window yelling at one another. In fact, Anne’s windows were blacked out, and the annex was supposed to be a silent zone all day long.

Are there other ways the play and the film influenced our idea of who she was?

Initially, the play ended with Nazis coming in and taking the family away, but the audience rebelled against that dark ending. They needed a conclusion that affirmed the inherent goodness of human beings.

Anne’s story lends itself to the idea that human suffering leads to redemption. People want it to be an example of good triumphing over evil. That’s something people often seek in Holocaust literature.

People tend to interpret the diary as redemptive instead of a portrayal of a very dark, painful reality. But millions of people were murdered. One of them was Anne.

IN MEMORIAM: A marker honoring Anne and her sister, Margot, at the site of Germany's Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, where they both perished. Their deaths, from typhus, came only a few days apart, most likely in February 1945.

page 4 of 5

Has Anne’s Jewishness been marginalized to make her story more universal?

The first person to turn the diary into a play was novelist Meyer Levin, who wrote a version that was quite Jewish. But Otto Frank didn’t think it would be accessible enough to a wide audience. Otto saw the diary as not just about Jews; the Nazis had discriminated against many other groups as well as Jews.

So the story’s Jewishness has been a question since the beginning of the diary’s popularity. The Anne Frank House has to deal with that, too. They have exhibitions and programs aimed at making Anne’s story relevant to today’s world. And Anne Frank ambassadors work for social justice all over the globe today.

The diary is a historical document, but is it also literature?

It’s both. I asked my students to try to write in Anne’s style. They found it incredibly difficult. She was an attentive writer who could really bring a scene alive.

During the war, the BBC put out a request for writings from those in hiding. When Anne learned of this, she started revising her diary heavily, and I think that’s when she started looking at her prose from a different perspective. She consciously crafts it for the reader. She wonders how other people will view her.

Even before she began revising, she entertained others in the annex by reading parts of the diary aloud. From the beginning, she wrote, at least in part, for an audience.

And Anne was a voracious reader. She learned how other people wrote, including Charles Dickens. It’s not hard to find Dickensian moments in the text.

If the Dutch have never caught on to the diary the way Americans have, why devote an entire transnational course to Anne Frank’s legacy?

We were challenging American and Dutch students to try to understand together what the war and the Holocaust were like for people from different cultures. For some of the Dutch students, the course offered them their first experience of meeting a Jewish person. The American students had to imagine walking on the same ground as Anne — and the many others who were taken away and murdered — once did.

Mike Lovett

Dawn Skorczewski

page 5 of 5

Did the course make the Holocaust more real for your students?

The course brought the facts of Anne’s historical situation to life: how and where she lived, how her situation compared to other Europeans’, and how and where she died. But it is also important for students to recognize that genocide is as much a reality today as it was in Anne’s time.

And it is important for me to learn how my students in a particular time and place experience the study of the Holocaust. This is what makes teaching so energizing for me — the class depends utterly on who is in the room, and what we talk about and discover together.

Can students studying traumatic events like the Holocaust start to feel like they themselves are participating in the trauma?

Shoshana Felman, a comparative literature professor at Emory, once wrote that her students were traumatized by watching Holocaust survivor testimonies. To study the Holocaust is to explore one of the darkest, most destructive moments in human history. People were traumatized by their experiences during the war and in the camps, and, if they survived, by their return to their former homes.

In our class, we studied USC Shoah Foundation video testimonies featuring Dutch men and women. This was in addition to our readings of the diary and articles about the diary, and lectures and visits from folks from the Anne Frank House and VU Amsterdam.

In seeking to understand others’ trauma, we become co-owners of the experience. We are not survivors of the trauma ourselves, but we join a community of people who bear witness to the trauma.

Sometimes this becomes overwhelming. But our experience of the intensity of the trauma becomes part of what we bring to our lives, and what we bring to conversations about genocide.

Jarret Bencks is a news and communications specialist in the university’s Office of Communications.