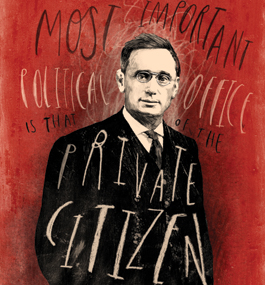

American Sage

A century after his appointment to the Supreme Court, Louis Brandeis is more relevant than ever, especially his ideas on social justice, the Constitution and democracy.

Peter Strain

by Philippa Strum '59

You were talking to Brandeis in your sleep again,” my husband said.

That wasn’t exactly a surprise. It was the early 1980s, and I was deep into writing a biography of Louis Dembitz Brandeis. Any biographer will tell you it’s impossible not to become completely enmeshed in the life and thought of a subject.

As a professor of American government and constitutional law at Brooklyn College, I had arrived at the point in my career where I thought I should undertake a biography of a U.S. Supreme Court justice. I considered William O. Douglas, but he was still on the court, and I wasn’t sure writing about a living person was either ethical or wise.

Brandeis died in 1941, and the last full biography of him had been written in the 1940s. Surely, it was time for another generation’s take on the man.

I’d been intrigued by Brandeis ever since I was a Brandeis University undergrad in the late 1950s, walking past the statue of him that had just gone up on campus. The judicial robe sailing out behind him made him look like an alarmingly big bird about to take off. I wondered then what he had done to deserve being cast in bronze, much less having a university named after him.

What an extraordinary man I encountered once I began my research. He pioneered savings-bank life insurance, fought the huge trusts that were rapidly taking over much of the American economy, and virtually invented the position of public-interest attorneys who provide free legal services for important social causes.

He negotiated settlements in major labor disputes, fashioned Woodrow Wilson’s first presidential campaign, created Wilson’s approach to regulating the economy, forged a new approach to constitutional interpretation, articulated the right to privacy and led the American Zionist movement.

And that was all before 1916, the year Brandeis was appointed to the Supreme Court. What he did in his pre-Supreme Court life and during his subsequent 23 years on the court left a lasting impact on American ideas and law.

The principles Brandeis laid down remain extraordinarily useful as the U.S. grapples with 21st-century challenges. His ideals are timeless, capable of providing guidance yesterday, today and into the future.

Here are a few examples.

The living law

In 1908, while Brandeis was still practicing law in Boston, the National Consumers League asked him to defend an Oregon statute limiting women’s work hours before a U.S. Supreme Court that scorned labor-protective legislation.

At the time, American courts took a static approach to judging, particularly in constitutional litigation. Case analysis was either historical, based on what judges thought a clause’s writers meant, or mechanistic, relying on what judges saw as the plain meaning of the words.

Brandeis, on the other hand, believed the Constitution is a living document, designed to be interpreted in light of current societal needs. (In today’s terms, that makes him more of a Ruth Bader Ginsburg than an Antonin Scalia.)

Departing radically from the norm, the brief Brandeis submitted to the Supreme Court in Muller v. Oregon devoted only two pages to traditional legal arguments and citations. But over 15 pages, he cited state and foreign laws that limited women’s work hours, then included 95 additional pages of sociological and economic data culled from reports by numerous American and British sources. The data were meant to demonstrate that maximum-hours laws for women served a useful purpose in an industrialized society and that the idea of such laws had already gained general acceptance.

His strategy succeeded. For the first time, the court upheld a law limiting hours, and praised Brandeis by name in its opinion. Lawyers were electrified. Requests for copies of his brief poured in from around the country.

The style of brief now known as the “Brandeis brief” soon became the norm in constitutional litigation. Think Brown v. Board of Education (1954), in which the NAACP used facts to demonstrate that “separate” was never “equal.” Think the cases then-attorney Ruth Bader Ginsburg argued successfully in the 1970s showing the harm done by laws that discriminated against women.

Or, more recently, think Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), in which a host of briefs pointed out that 72 percent of Americans already lived in states that recognized gay marriage.

Today’s fact-based jurisprudence is a major part of the Brandeis legacy.

‘The right to be let alone’

The Fourth Amendment grants people the right against “unreasonable searches and seizures” of “their persons, houses, papers and effects.”

So, many Americans were shocked when Edward Snowden announced in 2013 that the National Security Agency (NSA) was monitoring their telephone calls and Internet communications. The U.S. government countered it was only doing what was necessary to protect Americans from terrorists.

In 1928, decades before the NSA was created, Justice Brandeis wrote a dissent to the decision in Olmstead v. United States, a Prohibition-era case that involved wiretapping by federal agents trying to catch bootleggers. The government argued, in words similar to those it would use almost a century later, that the wiretapping was necessary to protect Americans from criminals. Besides, wiretapping didn’t involve physically entering anyone’s home, so the Fourth Amendment didn’t apply. The majority of the justices agreed.

Peter Strain

page 2 of 3

Brandeis was outraged. Back in 1890, he and his law partner had written a Harvard Law Review article that, for the first time, argued the right to privacy was inherent in American law. Now, in his Olmstead dissent, he noted that a constitutional principle, “to be vital, must be capable of wider application than the mischief which gave it birth” — in other words, that the spirit of an amendment has to be interpreted in the context of the historical moment.

He also reminded the court it had long held that the Fourth Amendment applied to the postal system, adding:

The evil incident to invasion of the privacy of the telephone is far greater than that involved in tampering with the mails. … The tapping of one man’s telephone line involves the tapping of the telephone of every other person whom he may call or who may call him. As a means of espionage, writs of assistance and general warrants are but puny instruments of tyranny and oppression when compared with wiretapping.

Then, declaring that “the makers of our Constitution … sought to protect Americans in their beliefs, their thoughts, their emotions and their sensations,” he penned some memorable prose that seems quite relevant today:

They conferred, as against the government, the right to be let alone — the most comprehensive of rights and the right most valued by civilized men. To protect that right, every unjustifiable intrusion by the government upon the privacy of the individual, whatever the means employed, must be deemed a violation of the Fourth Amendment.

As for the government’s insistence that the wiretapping was necessary for law enforcement, Brandeis wrote:

Experience should teach us to be most on our guard to protect liberty when the government’s purposes are beneficent. … The greatest dangers to liberty lurk in insidious encroachment by men of zeal, well-meaning but without understanding.

The phrase “the right to be let alone” has since been invoked in almost every constitutional lawsuit and decision involving privacy, including not only instances of government spying but in such areas as reproductive freedom and gay rights.

Speech and the citizen in a democracy

In 1920, the state of California found a woman named Anita Whitney guilty of “criminal syndicalism,” or breaking the law by working for political and economic change. Whitney was convicted of helping to organize the California Communist Labor Party, which advocated change not just through the ballot box but through strikes and demonstrations as well. Given the anti-Communist, anti-labor hysteria of the post-World War I years, that was considered subversive.

The Supreme Court upheld Whitney’s conviction. Brandeis concurred for procedural reasons yet wrote an opinion that reads like a dissent. Invoking the words of the First Amendment (“Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech”) and the Founding Fathers who penned them, Brandeis described the relationship between speech and democracy. It was the first time a Supreme Court justice had done so.

Brandeis’ argument remains so central to this country’s uniquely permissive speech jurisprudence that it is one of the most-cited opinions in American law. He wrote:

Those who won our independence … believed that freedom to think as you will and to speak as you think are means indispensable to the discovery and spread of political truth; that, without free speech and assembly, discussion would be futile; that, with them, discussion affords ordinarily adequate protection against the dissemination of noxious doctrine; that the greatest menace to freedom is an inert people; that public discussion is a political duty, and that this should be a fundamental principle of the American government. … [The Founding Fathers] knew … that the fitting remedy for evil counsels is good ones.

In other words, the freedom to speak is the freedom to hear. Without access to all ideas, good and bad, how can the citizens of a democracy decide which policies are best and which politicians to support? Speech can be dangerous, and Brandeis acknowledged that. He nonetheless believed in the ability of the citizenry to sort out bad ideas from good ones, even if that takes some time, and so he opposed restricting speech if there is time for the bad ideas to be countered by the good.

His opinion continues:

Those who won our independence by revolution were not cowards. … They did not exalt order at the cost of liberty. To courageous, self-reliant men, with confidence in the power of free and fearless reasoning applied through the processes of popular government, no danger flowing from speech can be deemed clear and present unless the incidence of the evil apprehended is so imminent that it may befall before there is opportunity for full discussion. If there be time to expose through discussion the falsehood and fallacies, to avert the evil by the processes of education, the remedy to be applied is more speech, not enforced silence.

If there is no immediate danger of lawlessness resulting from speech and there is time to counter “bad” speech with “good” speech, bad speech has to be allowed. In fact, bad speech has to be as protected as good speech, Brandeis believed, because the government cannot be trusted to define the “bad” and the “good.” The cure for bad speech is not government intervention but good speech, and lots of it.

What Brandeis could not anticipate, of course, was the invention of the Internet, with its wonderful ability to give everyone a forum for speech, along with its equally worrisome provision of a platform for cyberbullying, revenge porn, terrorist recruitment and other such phenomena. How do we apply the Brandeisian principles to these problems?

Peter Strain

page 3 of 3

Remember that Brandeis insisted that the Constitution is a living document and that problems brought to the court have to be examined in light of current circumstances. He enunciated principles, not panaceas for present or future societal problems.

One of these principles is that the right to speech is inextricably tied to the responsibility to participate in the democratic process. “Full and free exercise of this right [of speech] by the citizen is ordinarily also his duty, for its exercise is more important to the nation than it is to himself,” he wrote in a 1920 case. A convert to the cause of woman suffrage, he had declared before the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment that he was convinced “not only that women should have the ballot, but that society demands that they exercise the right.”

|

|

Sidebar Story |

|

Democratic citizenship implies duties as well as rights, said Brandeis. Uninvolved citizens — the ones who do not answer bad speech with good speech — are shirking their responsibility to learn about the issues of the day, to help think through answers, to engage other citizens in discussion and to make their views known to policymakers.

These two principles — that speech must be allowed unless there is immediate incitement to crime, and that all citizens have a responsibility to counter bad speech with good speech — still resonate today. It falls to us to work out how to apply them.

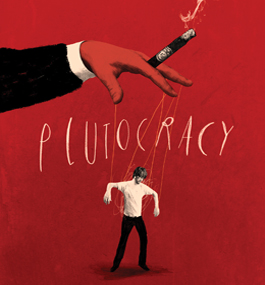

Too big to fail

Brandeis was particularly concerned about huge banks and other overly large corporations that used “other people’s money” — a phrase that served as a title for one of his collections of essays, speeches and judicial opinions — to amass enormous power that might be wielded in ways detrimental to society.

He believed a business became inefficient when it grew so large that the people at the top could not possibly know all the details of what the business was doing. Efficiency, to him, wasn’t just about making money; it also meant contributing to the general welfare — which every business ought to do.

“If the Lord had intended things to be big, he would have made man bigger — in brains and character,” Brandeis told a U.S. Senate committee in 1911.

In some instances, big trusts had amassed “such concentration of economic power that so-called private corporations are sometimes able to dominate the state,” Brandeis wrote in a 1933 opinion. The effects on “the lives of the workers, of the owners and of the general public” were so “fundamental and far-reaching” that the country was in danger of becoming subject “to the rule of a plutocracy.”

Workers’ lives were of great concern to Brandeis. He supported maximum-hours and minimum-wage laws for men as well as for women, and fulminated against irregularity of employment. Work situations that underpay employees and allow them too little time for leisure and for educating themselves about the pressing public issues of the day endanger both the decent lives to which all people are entitled and the democracy in which they live, he believed. Employment ought to be regular, and workers ought to be paid what today would be called a living wage.

Consider the economic crisis of 2008 or 21st-century income inequality. Brandeis’ thinking on the pitfalls of bigness and the need for a living wage could not be more pertinent.

‘The last word’

A great admirer of the ancient Greeks, Brandeis regarded the Periclean Age as a model democracy that held important lessons for Americans. A journalist who interviewed him in 1916 reported wryly, “Euripides, I now judge, after having interviewed Brandeis on many subjects, said the last word on most of them.”

When I mentioned this at the dinner table one evening in 1980, my 12-year-old daughter responded, “Well, Mom, to hear you, Brandeis had the answers to everything.”

Not quite. But his is a legacy of which Brandeisians can be proud, and one to keep in mind as we ponder the many challenges that face us today.

Philippa Strum, a senior scholar at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and professor of political science emerita at City University of New York, has published widely on the U.S. Supreme Court, the U.S. presidency, civil liberties, and women and politics. She is the author of “Louis D. Brandeis: Justice for the People” (1984), nominated for the Pulitzer Prize in biography, and “Brandeis: Beyond Progressivism” (1993).