The Souls of Rich Black Folk

Pulitzer Prize winner Margo Jefferson ’68 looks back at growing up in an affluent black enclave in Chicago in a powerful new memoir, “Negroland.”

by Lawrence Goodman

As a child, Margo Jefferson ’68 wore her hair straight. It was naturally curly, but Jefferson is black, and whites set the standard of beauty back then. Everyone wanted to look like Brigitte Bardot or Elizabeth Taylor. Jefferson, like many black girls at the time, used a hot comb and a curling iron to undo her frizz. Every night, her mother slicked her head with oil to keep her hair in place.

Jefferson grew up in an affluent black enclave on the South Side of Chicago. It was part of the area known in the 1950s and ’60s as the Black Belt, but Jefferson prefers to call it Negroland, a word she also used as the title of her acclaimed 2015 memoir, published by Pantheon Books.

Negroland existed apart from both white and mainstream black society, a hermetic world with black-owned department stores, theaters and nightclubs. There were riding stables and tennis clubs. Society clubs with names like the Links, the Moles and the Royal Coterie of Snakes threw formal dinner parties and cotillions. “We thought of ourselves as the Third Race,” Jefferson writes in “Negroland,” “poised between the masses of Negroes and all classes of Caucasians.”

Jefferson took ballet as a child. She studied classical piano. In high school, she acted in “Pygmalion” and “The Taming of the Shrew.” The future Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and New York Times cultural critic wore a short skirt and a preppy white sweater, and shook pompoms as the captain of the cheerleading squad. At her senior prom, she was selected to play Debussy’s “La Cathédrale Engloutie” for her classmates.

But for all its luxury and affluence, Negroland wasn’t an easy place to grow up. In fact, as Jefferson writes in her memoir, it “made and maimed” her.

In “Negroland,” Jefferson can come across as intense, aloof, cold and unhappy in her career as a writer. “Her life has gone wrong,” she writes about herself. She’s “ashamed of what she is.” “She knows she should love what she does [writing], but she doesn’t.” “About love and sex, she should have been adventurous, not wary.” And that’s just the first chapter.

But conversing in a small, trendy restaurant in Manhattan’s West Village, around the corner from the apartment where she’s lived since the 1970s, Jefferson is charming. She smiles, laughs, makes jokes. Full of energy, she gesticulates as she talks, stabbing at the table to emphasize her points.

Today, she sports curly blond hair. She freely admits she started dyeing it in the early 2000s to hide the spreading gray. You might be tempted to see her choice of color as a serious statement about race — a black woman with blond hair — or a rebellion against the enforced straight hair of her childhood. She portrays it as the result of an inner playfulness. “Is it kind of fun to be the brown-skinned person with blond hair? To do the unexpected?” she says. “Sure is.”

|

|

Sidebar Story |

|

She takes a similar approach to fashion. At the restaurant, she’s wearing a hooded vest with patches of tweed, slim black pants and a black sweater. She shops at vintage and boutique clothing stores. She’ll go “odd and eccentric one day, a little more preppy the next day, then a little faux ethnic or a little faux proper,” she says. She likes to mix it up.

Her journey from her cloistered upbringing with its suffocating mores and code of behavior to full self-awareness and autonomy required enormous inner strength. The freedom to tinker with her identity as she pleases was hard won.

Jefferson is a professor of nonfiction writing at Columbia University. Scrounge around Facebook and you will find postings from former and current students heaping praise on her. She spent 11 years at the Times, which she joined as a book reviewer in 1993 after stints as an editor and writer at Newsweek and Vogue, and professorships at Columbia University and later NYU. In 1995, the same year she won the Pulitzer for her criticism at the Times, she switched to reviewing theater.

Michael Lionstar

Margo Jefferson '68

page 2 of 4

Her writing showed a deep breadth of knowledge and reflected her commitment to tying the arts to political and social issues. But she could be unsparing in her criticism, like when she described acclaimed theater director Daniel Sullivan’s staging techniques as “efficient, never organic … props are always used predictably.”

She says she wanted to turn her critic’s eye on herself in “Negroland.” Perhaps she is too harsh on herself. At the very least, she doesn’t give herself enough credit for her achievements or strength in overcoming personal and professional obstacles. Writers spend a lot of time inside their heads. They can focus too much on their faults, forgetting they’re no worse than anyone else’s.

The idea for a memoir first struck Jefferson in the late ’90s, when her classmate Susan Dickler ’68 visited Chicago. Jefferson invited her to a tea hosted by her mother. Afterward, Dickler told Jefferson, “You have to write about this world.”

First, though, she had to write another book, “On Michael Jackson,” which explored America’s fascination with the King of Pop. In 2004, Jefferson left the Times so she could devote herself to finishing it. When it appeared two years later, Publishers Weekly wrote, “[Jefferson’s] slim, smart volume of cultural analysis may remind readers of Susan Sontag’s early, brilliant essays on pop culture.”

She committed herself fully to a memoir in 2010 when her only sibling, Denise, died of ovarian cancer at age 65. An accomplished dance educator, Denise was the director of the Ailey School at the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. Margo, who has never been married and doesn’t have children, says she suddenly felt an urgency to make a record of her life, that she had a “sense that time was fleeting.”

Jefferson’s ancestors were slaves, white slave owners, and free men and women. They quickly moved up the social ladder. They worked as farmers, musicians, lawyers, businesswomen and doctors. Jefferson’s father was a pediatrician. Her mother was a social worker who left the workforce to take care of her kids. She also became one of Negroland’s leading socialites.

In 1903, W.E.B. Du Bois wrote about the “Talented Tenth,” the select 10 percent of any racial or ethnic group qualified to lead the rest of its members forward. South Side African-Americans thought of themselves this way and then some. “We weren’t raised to be average women,” Jefferson writes in “Negroland.” “We were raised to be better than most women of either race.”

The pressure to succeed was enormous. It also bred elitism. Negroland denizens looked down their noses at poorer blacks. They blamed them for giving African-Americans a bad name and feeding white prejudice.

But the snobbery also masked insecurity. No matter what they did, whites would still never accept them. They lived with a constant and real fear that their hard-earned privileges would be taken away from them. “Most white people want to see us as just more Negroes,” Jefferson’s mother told her.

IMPECCABLE: Margo (foreground) and her older sister, Denise, during a visit to Canada, around 1956.

page 3 of 4

Jefferson’s family lived with an unrelenting fear that whites would decide to take away what African-Americans had worked so hard to achieve. “Nothing highlighted our privilege more than the menace to it,” she writes. “We had the moral advantage; they had the assault weapons of ‘great civilization’ and ‘triumphant history.’”

At the time, the proper response wasn’t thought to be resistance. Instead, your behavior as a female in Negroland had to be impeccable. You never wanted to do something whites could use to fuel their racism or aggression. Jefferson grew up feeling a crippling self-awareness about her behavior. She could never misbehave.

In her book, she recalls being 5 years old at a dinner party thrown by her parents and blurting out, “Sometimes I forget to wipe myself.” There was laughter but also an underlying anxiety. The unspoken message was clear, Jefferson writes: “Your mistakes — bad manners, poor taste, an excess of high spirits — could put you, your parents and your people at risk.”

Negroland’s residents stood apart from everyone else, black and white. They felt at home only with one another. By the time Jefferson arrived at Brandeis, she was, on the outside, the model black woman her mother demanded she become.

Inside, she was full of self-doubt and insecurity.

Jefferson wound up at Brandeis almost by chance. She was touring small liberal-arts colleges in the Northeast — Wheaton, Wellesley and Pembroke (the women’s college at Brown University). Brandeis wasn’t on the list. Then one day her train got stuck in a rainstorm, and a young Brandeis professor happened to be sitting nearby. They struck up a conversation. “Think about Brandeis,” he said. “It’s an interesting place.” She followed his advice.

She liked the school’s progressive culture and that it was co-ed, still something of a rarity in the late ’60s. There were few African-American students. But her high school, the progressive University of Chicago Laboratory School, had also been mostly white. She was used to it.

“It was a very good time to be at Brandeis,” Jefferson says. She became part of the Black Power movement. She took classes with Herbert Marcuse, the German social critic and prominent New Left theorist, and poet Allen Grossman. Students protested Vietnam, debated the place of black literature in the canon, and discussed Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael.

“If you were really thinking about all these things, you had to challenge not only your assumptions but your behaviors,” Jefferson says. “I rethought my snobbery.”

Her parents didn’t quite know what to make of what was happening. Although, of their two daughters, Denise was more aggressive in confronting them, Margo also had her quarrels. She remembers arguing with her father about Thurgood Marshall, the lawyer and Supreme Court justice who furthered the cause of civil rights but also supported the Vietnam War. Jefferson’s father thought Marshall could be forgiven. His daughter thought the famed jurist was beyond redemption.

Courtesy Brandeis University Archives and Special Collections

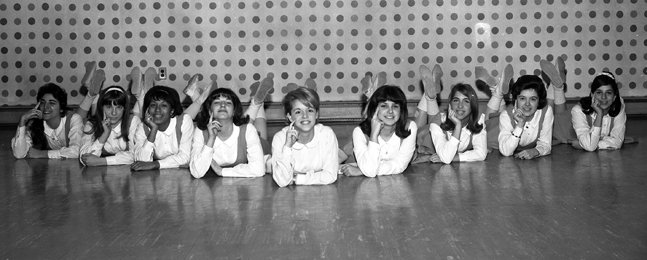

SCHOOL SPIRIT: Jefferson (third from left) joined the Brandeis cheerleading squad as a first-year student.

page 4 of 4

By the end of her four years, the political climate had shifted. Other blacks now looked down on privileged African-Americans like her. “We were a corruption of The Race, a wrongful deviation. We’d let ourselves become tools of oppression in the black community,” she writes in “Negroland.” “We’d settled for a desiccated white facsimile and abandoned a vital black culture.”

Around this time, a sadness set in that Jefferson recognized as depression. She was furious at herself for not achieving the success her parents expected of her. And she hated herself for still being so much like them. She couldn’t make it as either a political radical or a dilettante. The depression, she says, was her anger and self-disgust turned inward. “It was a secret revenge,” she says. “‘You think you’re little Miss Perfect? Oh, please.’”

A few years after graduating, the depression grew worse. She strongly considered suicide, she writes in her memoir. The pressure to succeed and perform felt overwhelming. “Every move I made had to be scrutinized in advance for its possible negative effects, its consequences, its effects on others,” she says.

Even in contemplating how to kill herself, she felt a burden to live up to standards. “You must set an example for other Negroland girls who suffer the same way,” she told herself. She practiced sticking her head in an oven but never worked up the courage to turn it on.

Jefferson plans to write another book. She doesn’t have a subject pinned down. She’s waiting for it to come to her. She says she’s in a new place as a writer. “I’m continuing to explore, to try to do things that not only interest and excite me, but also scare me,” she says. “Negroland” “was a turning point for me in that way. It’s huge.”

She recently came across a photo of herself on the cover of a journal called Feminism and Socialism, taken soon after college. She stands between two white friends. It’s an image of solidarity, people power and racial harmony.

Looking at the photograph, you can see the distance Jefferson had traveled from her Negroland childhood. She sports an impressive Afro. She wears hoop earrings and an African print dress. But her transformation wasn’t quite as radical as it seems. She bought the dress at Saks Fifth Avenue.

“We live on many different levels,” Jefferson says. “The contradictions and symmetries — it’s all good.”