Arrested Development

Daniel Zalkus

by THERESA PEASE

Anyone who’s heard the theme song to “All in the Family” suspects there was a long-ago time when “girls were girls and men were men.” But, observers point out, things have changed on both ends of that equation: In post-baby boomer society, you might say that girls are women — and men? Well, they’re stuck in a seemingly endless childhood.

One of those observers is Kay Hymowitz ’71, whose “Manning Up” (Basic Books, 2011) hits the point hard with cover art showing a toddler togged out in a business shirt and tie, staring down at oversize dress shoes.

Despite the book’s provocative subtitle (“How the Rise of Women Has Turned Men Into Boys”), Hymowitz insists she is neither blaming women nor damning men for this massive shift in gender roles, but rather describing seismic changes in our culture that reflect economic and social evolution.

Some of it you’ve heard before. A generation or two ago, males grew up knowing what would happen after they finished their education: marriage, fatherhood and a lifelong career path that might start out in a factory or on a farm. Toiling 40 hours a week for 40 years, they would climb the ladder of success and support their dependent families as their fathers did before them.

“Men knew that something was expected of them, and they felt needed,” Hymowitz comments.

Recently, though, the demise of widespread industrial work in the United States has led to what economists term the “knowledge economy.” In other words, even as jobs requiring manly brawn (not to mention a higher tolerance for grime and repetition) began to vanish, new career paths proliferated in areas like communications, the arts, education, medicine, law, publishing and other humanistic pursuits that appeal to women and play to their talents.

Against this backdrop, women are “outperforming men,” says the author, who has delivered her message on the “Today” show, done national PBS interviews and dozens of other media appearances, and seen the book excerpted in a Wall Street Journal article headlined “Where Have All the Good Men Gone?”

Photo by Mike Lovett

page 2 of 2

“We know that 57 percent of our college graduates are women. Most of our master’s and doctoral degrees are going to females. Women in their 20s and 30s are more likely to own a co-op or a condominium than men are. And single, childless women are now outearning men of the same age,” claims Hymowitz, a former journalist who does sociological research and analysis for the Manhattan Institute, a free-market think tank.

In the face of fierce competition from these new alpha females — and without the looming social imperative to marry and take care of someone — some guys are simply opting to float indefinitely in a sort of suspended adolescence, Hymowitz says. Their determination not to wed or to pass any of the time-honored thresholds into adulthood puts one in mind of the musical version of “Peter Pan,” where the title character stubbornly sings, “Never gonna be a man. I won’t! Like to see somebody try and make me.”

In “Manning Up” she has identified a new archetypal character on the social scene and a whole new stage of life. She calls the former the “child-man” and terms the latter “preadulthood.”

To understand both, you need look no further than popular culture images.

Take Adam Sandler. Well, that is, if you can take Adam Sandler. The poster boy for childmanhood, who has publicly described himself as “not particularly talented” and “not particularly good-looking,” has become a Hollywood megastar, appearing in arrested development flicks that have grossed some $2.5 billion worldwide.

Citing an example, Hymowitz synopsizes Sandler’s “Big Daddy” thus: “A law school-grad slacker living off insurance from a car accident hangs out with an orphaned boy to impress his girlfriend, and they do little boy things together. Jokes about pee, vomit, spit, feces, farting, Hooters, breasts and sex, and people falling out of windows and being eaten by crocodiles are what passes for plot.”

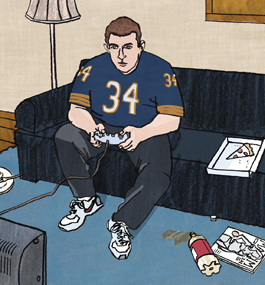

Unhappily, such characters do not exist only in fiction. And when they’re not farting or boasting about farting, these modern heroes are playing video games (on average, two hours a day) or reading “lad magazines” such as Maxim, which offers features like “The Five Unsexiest Women Alive,” “Confessions of a Strip Club Bouncer” and “Sixteen People Who Look Like They Reek.”

Hymowitz sets aside a popular contemporary male complaint that today’s high-achieving women only want guys who are unusually handsome or rich. But she admits that, while some girls raised on these new stereotypes are attracted to crude jerks, others are holding out — often unsuccessfully — for partners who are educated and civilized adults. One result is that marriage is being delayed or sidestepped by members of both genders — in women’s case, until the alarm on their biological clock is buzzing loudly. Another is the burgeoning popularity of sperm banks and single motherhood.

“Research shows that most ‘choice mothers,’ as they call themselves, would much prefer to have a child with a father, but say it has been impossible to find a husband they consider suitable,” Hymowitz notes, predicting that this trend will continue and even expand.

This is not to say marriage is dead. Indeed, the majority of college-educated men and women still wed and have children, the author says — but that majority has declined from 90 percent a few years ago to 80 percent today.

While it’s impossible to predict the future, Hymowitz says in her final paragraph that one thing is clear. “The profound demographic shift toward preadulthood is not going to go away; the economic and cultural changes are too embedded, and for women, especially, too beneficial to reverse,” she writes. “Both sexes say they want to have satisfying family lives. If that’s going to happen, young women will have to get a better understanding of the limitations imposed by their bodies. And young men? They’ll need to man up.”

Kay Hymowitz holds an M.A. from Tufts and an M.Phil. from Columbia in English literature. She is a contributing editor of the Manhattan Institute’s City Journal.