Please Don’t Rock the Boat

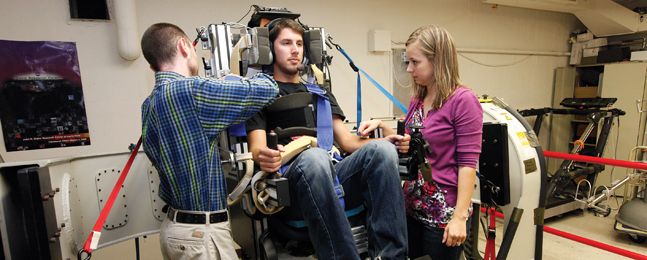

Photo by Mike Lovett

If you’ve ever pulled an all-nighter to finish a paper or endured a sleepless night with a colicky baby, you know how deeply lack of sleep can affect your ability to think and respond, physically and mentally. Add a constant state of motion to sleep deprivation and you stir in a whole new dizzying dimension to the experience.

The Ashton Graybiel Spatial Orientation Laboratory at Brandeis is one of only two labs in the country capable of investigating sensory motor adaptation, motion sickness and the effects of varying force environments on the body, with a focus on the weightless environment of space.

But in summer 2009, the U.S. Navy asked the lab to conduct a three-year study to support an entirely earthly application: crew performance on small combat ships. The study’s goal was to determine how exposure to motion, when combined with different levels of sleep deprivation and fatigue, would affect performance in cognitive, sensory and motor areas.

Testing the ability to stay alert while sleep deprived in a stationary laboratory is nothing new, says Paul DiZio, associate professor of psychology, associate director of the Graybiel Lab and chair of the psychology department. But current fatigue models for predicting performance on small ships have not been tested at sea or under conditions of repetitive whole-body motion.

The lab recruited 60 student subjects, who were paid either to limit their sleep to four hours per night or lavish in slumber for eight. During the day, they performed tasks either while stationary or while in motion. One experiment involved sitting in a horizontal linear oscillating swing suspended from a high ceiling on four steel posts. The swing moved from left to right at a fixed frequency, instead of fore and aft.

Self-described “scientific masochist” Simon Zahn ’12 was one study subject who was not about to let any queasiness interfere with the generation of new knowledge. During the study, the physics and math major received two full nights of sleep and underwent daytime tests that involved sitting in the motion swing four times a day, for 80 minutes each time.

“I was fortunate to vomit only once,” says Zahn. “A few people vomited multiple times.” “Ship motion is a complex motion, with left, right, up, down, rocking and pitching back and forth,” says DiZio. “The left-right motion in previous studies has been shown to be a large component in motion sickness, so it was reasonable to start with this, as the motion environment had to be something that we could quantify in a laboratory yet must also be relevant to ship motion.”

One part of the study investigated the interaction of sleep and motion; the other part, using computer-generated images and procedures, assessed a range of functions, including attention, perception, motor control and perceptual learning.

The researchers determined that sleep deprivation increases both measured sleepiness and motion sickness. Similarly, swing motion increases both sleepiness (similar to the way rocking increases sleepiness in babies) and motion sickness. Furthermore, the effects of sleep deprivation and motion do not interact but add together.

“As we looked at all the performance test results together, a consistent pattern seemed to emerge,” says DiZio. “The more cognitive effort the task requires, the more likely and the more extensively performance on that task will be degraded by sleep deprivation and motion.” A limitation of the study, DiZio says, is that the researchers stopped swinging subjects when their motion-sickness rating reached midway between feeling good and feeling very motion sick, to prevent them from feeling too ill. “More than half of the swinging subjects would not have been able to do any of the tasks in the latter portions of most sessions if we did not pause the test. This means performance decrements were underestimated,” he explains.

For his part, Zahn believes getting a bit green about the gills in the name of scientific understanding was well worth it. “To be able to contribute to research, to see what it’s like to be a scientist, is a fantastic opportunity and offers priceless knowledge for students who are considering going into this field,” he says.

— Susan Chaityn Lebovits