A Tree of Life

Taxol pioneer is celebrated for a lifetime of fighting cancer.

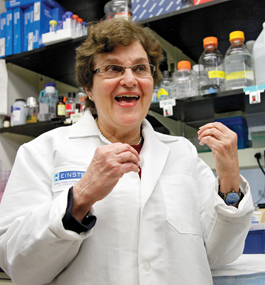

Mike Lovett

Susan Horwitz’s groundbreaking discoveries about Taxol helped make it a blockbuster drug.

by DAVID MCKAY WILSON

Susan Band Horwitz, Ph.D.’63, recalls being awestruck by the elegant architecture of Taxol, a small molecule isolated from the poisonous bark of the Pacific yew tree. Her landmark research would help turn the molecule into one of the world’s most effective anti-cancer drugs.

“I thought — that’s a very beautiful structure,” says Horwitz, the Rose C. Falkenstein Professor of Cancer Research at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, N.Y., “and I had an interest in looking further.” That was 1976, when she told the National Cancer Institute that she’d like 10 mg of Taxol to study in her lab.

More than a decade earlier, in 1962, a botanist gathering potential anti-cancer compounds had scraped the bark from an old-growth yew tree in Oregon, taking the first step in the long and complex discovery of what became one of medicine’s blockbuster anti-tumor drugs. By the time Taxol arrived in Horwitz’ lab, scientists knew that it held promise fighting tumors. But no one knew how it did this — and understanding its mechanism of action was key to harnessing its power as a chemotherapeutic agent.

As luck would have it — and Horwitz says luck plays a part in many scientific discoveries — she’d welcomed cell biology doctoral student Peter Schiff ’75 into her laboratory just after he’d received his undergraduate degree from Brandeis. During his first year there, Schiff had begun investigating the behavior of microtubules — proteins that are part of the cell’s skeleton and play a crucial role in cell division. Still looking for a topic for his doctoral thesis, Schiff became interested when Horwitz mentioned a possible study of Taxol.

“I told him he could work on the drug for one month and determine whether he could build it into a thesis project,” says Horwitz. Schiff soon found that the microtubules in a cell behaved quite differently in the molecule’s presence. Microtubules are dynamic structures necessary for normal cell replication. In the presence of Taxol, however, they became stabilized, halting cells from further growth. The study of Taxol became Schiff’s doctoral thesis. He was lead author and Horwitz was senior author of a groundbreaking 1979 paper for the journal Nature elucidating Taxol’s previously unknown mechanism of action involving microtubules.

It took 13 years after the Nature article appeared for Taxol to gain FDA approval for the treatment of ovarian cancer. Two years later, it was approved for breast cancer, and by 1999 lung-cancer patients were being treated with Taxol. Since 1992, more than 1 million cancer patients have been treated with the drug. “I’m still studying Taxol,” says Horwitz, who is also researching compounds from sponges found in ocean waters near the Bahamas and New Zealand, which she hopes may one day develop into new anti-tumor drugs.

Her research achievements have brought a flood of accolades, including the American Cancer Society’s Medal of Honor and induction into the National Academy of Sciences. This year, she received the American Association for Cancer Research Award for Lifetime Achievement in Cancer Research.

Horwitz acknowledges that the cure for all cancers won’t be found anytime soon. But she sees a day when many forms of cancer will be treated as chronic diseases, with new treatments keeping the cancers at bay. “We want to make cancer into a disease that you can live with and still have a good quality of life,” she says.

There were few women in science research when Horwitz, a biology major from Bryn Mawr College, looked to study biochemistry on the graduate level in the late 1950s. Horwitz was attracted to Brandeis, which had two married women on its science faculty and a new biochemistry department opening that fall.

“Brandeis was a terrific fit,” says Horwitz, who lives in Larchmont, N.Y. “There was superb science and yet a relaxed atmosphere. And after five years, I was not only a different person scientifically; I was a very different person because I was married after my third year and by graduation had a set of 1-month-old twin boys.”

She’d met her husband, Marshall Horwitz, in the Brandeis biochemistry lab while he was doing research one summer. He was destined for a career as a physician/scientist. She wanted to become a scientist and at Brandeis focused on the study of chemical reactions catalyzed by enzymes. But she also wanted time to raise her boys, and she couldn’t find a lab studying enzyme kinetics that would let her work part time. She turned to her thesis adviser, Professor Nathan O. Kaplan, who connected her with the pharmacology department at Tufts University School of Medicine, which let her work three days a week exploring the behavior of small molecules used in the treatment of cancer.

“I hadn’t heard of pharmacology and wasn’t that interested in it,” she says. “But then I started to learn about anti-tumor drugs. And it turned out to be one of the best things I did in my life.”

By the time her boys entered first grade in 1970, she was ready for fulltime cancer research at Einstein. “She was a great mentor,” says Schiff, now vice chairman of NYU School of Medicine’s Department of Radiation Oncology. “Working in her lab was kind of like working for your mother. She’d hover when she thought she needed to hover, and when she felt confident, she’d let you be, to work independently.”

The drug’s success reaffirms what Horwitz discovered long ago when she first tackled the challenges of molecular pharmacology in her first postgraduate laboratory. “I loved the idea that small molecules could do great things,” she says.