Every Head He’s Had the Pleasure to Know

Henry Grossman ’58 has enjoyed a long career of photographing icons, including four who became his friends: John, Paul, George and Ringo.

by Susan Piland

Brian Epstein wasn’t happy.

In early 1965, as Beatlemania raged on, the Beatles manager learned that Life magazine had photos showing John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr at home with their wives and girlfriends. Worse yet, Life planned to syndicate the photos to publications around the world.

Epstein didn’t want the shots widely released. The maestro behind the Beatles’ public image, he preferred that young fans didn’t know the group had significant others of any kind, married or unmarried.

He phoned Henry Grossman, the American photographer who had taken the shots for Life, to complain. “We have never even let a British photographer into their homes,” Epstein said.

The next day, he cabled Grossman: “Have just seen the photographs. Disregard phone call. Can I have a set?” The calm intimacy captured by the photos had disarmed even the micromanaging manager.

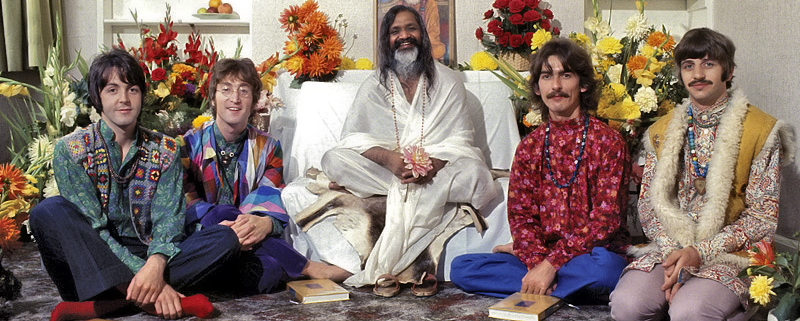

Nearly five decades later, photographs taken by Grossman ’58 are still captivating Beatles fans. In fact, the sheer scale of what Grossman recently made public has pitched many into a latter-day frenzy. Late last year, a small publishing company called Curvebender released a collection titled “Places I Remember” — a handsome 528-page, 13-pound coffee-table book containing more than 1,000 of Grossman’s Beatles photos, most of them never before published.

And it’s a mere fraction of what has been lying undisturbed in the photographer’s archives. Between 1964-68, Grossman shot more than 6,000 Beatles images. Some were taken when he was shooting on assignment for major publications like Life, Time and the London Daily Mirror. Others were taken behind the scenes, when he was hanging out with the Beatles as their friend.

McCartney, who wrote the introduction to “Places I Remember,” puts it this way: “Even though the Beatles had lots of photographs taken of them, occasionally one of the photographers would be out of the ordinary; Henry Grossman was one such photographer. We allowed him access to our public and private lives. His photographs are an important record of a very special period.

“Plus, he’s a good guy.”

page 2 of 6

|

|

(Photo by Henry Grossman) |

The artist’s eye

An acclaimed photographer, Grossman, 76, isn’t only a photographer. He attended Brandeis on a theater arts scholarship. He studied acting under Lee Strasberg at the Actors Studio. For years, he dedicated himself to opera singing, making it to the Metropolitan Opera stage as a principal tenor from 1991-92 — he had small roles in “Der Meistersinger” and “Ariadne auf Naxos” — and to Broadway as an actor, with a two-and-a-half-year run in “Grand Hotel.”

All this training as a performer informs his shooting, Grossman says: “As an actor, first of all, I love people. Second of all, as an actor, I study people. Somebody once said an artist sees not only what a situation is becoming but where it’s going.”

A quick glance at Grossman’s website, www.henrygrossman.com, reveals the wide-ranging photo assignments to which his love of people has led: Nelson Mandela, Isamu Noguchi, Meryl Streep, Muhammad Ali, Martha Graham, Jimmy Carter, Leontyne Price.

In 1964, Grossman was sent to photograph the Rolling Stones’ first New York City press conference. “I didn’t like them, and I never went back,” he says.

The Beatles were different. When Time asked him to shoot the group’s first “Ed Sullivan Show” performance that same year, it was the beginning of a genuine friendship.

“I liked them,” says Grossman. “They were bright, intelligent, funny. And they had a great sense of joy.”

The classical-music maven didn’t understand the Beatles’ music and never listened to it, which paradoxically may have eased the way to becoming friends with them. “If I had known more about them or known more about how big they were going to become, maybe I would have been more avid in certain ways,” Grossman says. “There would have been more at stake.”

Instead, he simply saw the Beatles as interesting people. They, in turn, could relax around him.

He became part of the extended family whenever he shot them for a magazine or a newspaper — when they were filming “Help” in the Bahamas and Austria, for instance. Or if he was near London for some other assignment — like getting stills of Richard Burton on a Dublin movie set — he’d stop by for a visit with one or more of the band.

Grossman always brought his Nikon along, sometimes two (one fitted with a wide-angle lens, the other with a telephoto). He took pictures of the Beatles working in the Abbey Road studio, talking with the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, playing with their kids.

Asked to describe what the foursome was like as subjects, Grossman says, “Real. There’s one picture of me on the beach with John. I’m posing, standing there with a real grin on my face. John’s just looking.

“I don’t think I’ve found a picture where any of them are muscularly posing for the camera,” he continues. “One of my favorite quotes is by Emerson. He says, ‘Stop talking. Who you are speaks so loudly I can hardly hear what you’re saying.’ The pictures of the Beatles, almost all of them — they are real. That was marvelous.”

One morning during the “Help” shoot in Nassau, as he ate breakfast with Harrison, Grossman reached for his camera to grab a particular shot.

“George looks as I would expect Hamlet to look,” he says. “Early morning, totally open, something going on in the mind, not trying to put anything on. It’s one of my best portraits.”

page 3 of 6

|

|

(Photo by Henry Grossman) |

Innocence and experience

Grossman was about five years older than the Beatles, a college graduate, well-traveled. Early on, they treated him like a big brother. He’d explain things they didn’t know. He told Harrison what a thesaurus is, then bought him one.

Another time, Grossman was at Harrison’s house, and saw what he assumed was a wall decoration.

“I said, ‘What’s that?’” Grossman remembers. “He reached up, took it down and said, ‘That’s a sitar, but I can’t find anybody to teach me how to play it.’ So I looked at him, and I said, ‘George, you make a lot of money.’ He smiled. I said, ‘You could find the best sitar player in India and bring him here for the summer to teach you.’”

The next time Grossman went to see Harrison, the guitarist answered the door in bare feet, and urged his visitor to take his shoes off, too. Harrison had been to India to study sitar with Ravi Shankar, and was settling into a more Eastern sensibility.

Despite their youth, the Beatles had depths that impressed Grossman. “I have a 25-minute audiotape of George and me talking about philosophy,” he says. “He was so far ahead of what I knew then and know even now, my God. This was an old soul. Someone who knew and had thought about everything.”

In 1967, Grossman shot the group for a Life cover. The Beatles were in their Swinging London finery. Grossman had never owned a pair of jeans. “I always wore chinos,” he says, “because I didn’t know whether I was going to photograph a bank president or a hobo, and I needed to be presentable.”

During the shoot, Grossman admired the double-wide psychedelic tie Ringo had on: “I said, ‘Ringo, I wish I had the guts to wear a tie like that.’ He came over and fingered my paisley tie, looked me in the eye and said, ‘Well, Henry, if you did, you would still be Henry, but with a bright tie!’”

It was, Grossman says, “one of the deep lessons I got from them.”

In his work, Grossman instinctively looks past the external for an internal truth. He got this from his father, etcher Elias Grossman, who created portraits of such figures as Einstein, Gandhi and Tagore from life.

Henry mastered the technical aspects of photography as a student at New York’s Metropolitan Vocational High School. At Brandeis, he developed and printed photos for Ralph Norman, the university photographer, to make money to send home to his mother (Elias had died when Henry was 11).

When dignitaries came to campus, Grossman photographed them in tandem with Norman or on his own. “Brandeis was a major, formative part of my life,” Grossman says. “What it allowed me to do was incredible.”

By the time he left the university — he spent a year pursuing a master’s in anthropology after getting his bachelor’s in theater arts — he had a single-spaced, three-column, three-page list of the famous names he’d shot, including Eleanor Roosevelt, Marc Chagall, David Ben-Gurion, Adlai Stevenson and Henry Kissinger.

page 4 of 6

|

|

(Photo by Henry Grossman) |

Documenting history

One week that Ben-Gurion was in New York for a talk, Grossman brought the portrait he’d taken of him to Time and Newsweek. Both magazines ran it in their next issue.

“Since Time was in the same building as Life, I went to show Life my pictures, too,” Grossman says. “The woman I talked to said, ‘Henry, if you want to work for Life magazine, you have to learn to take five less-good but more-storytelling pictures.’ That was the beginning of my working for Life.”

Meeting John Kennedy was another big break. Grossman first photographed Kennedy in 1960 on the day he announced his run for the U.S. presidency. Hours after making his announcement in Washington, Kennedy flew up to Boston to appear on Eleanor Roosevelt’s WGBH-TV show, “Prospects of Mankind,” which was taped on the Brandeis campus. In Grossman’s portrait, the young candidate looks downcast, almost haunted. Kennedy staffers called it the “eyes” portrait.

Whenever Kennedy came to Boston or New York, Grossman, who was still a student, would take more photos, which he’d give to the campaign. “I got to know Kennedy and his people,” he says. “They used one of my pictures of Jack and Jackie in a car during a ticker-tape parade in the New York campaign headquarters. After he was elected, it was hung in the press office, about six feet long.”

Working as a freelancer after Brandeis, Grossman photographed the president and the first lady a number of times on assignment. In a sad, strange twist, the morning after Kennedy was assassinated, Grossman was at the White House. “I saw everyone reading The New York Times,” he says, “and the pictures on the front page looked familiar. They were both mine, one of Lyndon Johnson and one of Kennedy.”

Five years later, Grossman was hired by the Robert Kennedy campaign to shoot pictures for a poster for the senator’s White House run. “I was sitting on a plane with Robert Kennedy, thinking, This is the next president of the United States,” Grossman says.

During the middle of one long day of speeches in the Midwest, the candidate caught a nap in the front seat of a car while an aide drove. Grossman’s photo of Kennedy’s fatigued, vulnerable posture, taken from the car’s back seat, seems to foreshadow his assassination, just a month away.

“It’s an eerie picture,” Grossman says.

page 5 of 6

|

|

(Photo by Henry Grossman) |

Tomorrow never knows

The wealth of previously unseen Beatles photos collected in “Places I Remember” provokes a simple question: Why didn’t Grossman ever try to market them?

“I recently looked at my files to see what I was doing at the time I was photographing the Beatles,” says Grossman. “And, my God, I had Broadway shows to photograph. I was going to the White House. I mean, all these things within a week or two around each of my Beatles shoots. So I’d get the negatives back, I’d put them in the file, and I was off doing something else.

“And I had no idea — they had no idea — how long their fame was going to last,” he says.

But as the years passed and the Beatles went from pop stars to cultural touchstones, why not sell the photos then? “Well, I was becoming an opera singer,” Grossman says. “I had to study music. I had to go to coaching. I was a busy photographer. I traveled a lot. I mean, busy! And it never occurred to me that someone would want to do a whole book of the pictures.”

Brian Kehew and Kevin Ryan, the partners behind Curvebender, discovered Grossman’s Beatles treasury completely by accident. After licensing a couple of his photos for “Recording the Beatles,” a book Curvebender published in 2006, they naively asked what other Beatles shots he had. They were gobsmacked by how many there were. And that practically no one had ever seen them.

In 2008, Curvebender published “Kaleidoscope Eyes,” a showcase of more than 220 images Grossman took during a single night at Abbey Road as the Beatles recorded “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds.”

Though “Places I Remember” is currently being offered as an expensive limited edition (prices start at $495), plans are in the works for a more affordable version that could be purchased on Amazon and at Barnes & Noble.

Beatles scholars and fans are poring over the book’s photos, hunting for fresh insights or incontrovertible confirmation. For instance, says Grossman, “I have a picture of John sitting in his living room with a guitar, watching television. Kevin went mad when he saw it. He said, ‘In interviews, John would say that he’d sit on the couch, turn the TV on with the sound off, and write songs. Yours is the only picture I’ve ever seen of that.’”

Many of the photos, Grossman says, show “the surround. You get to see who was there, what was going on.” Storytelling pictures, in other words.

page 6 of 6

|

|

(Photo by Henry Grossman) |

Grossman, who lives on Manhattan’s Upper West Side near the Museum of Natural History, is still a busy photographer. He shoots dress rehearsals at the Metropolitan Opera, and does portraits of opera stars. Music runs in Grossman’s family. His son is an associate principal bassist with the New York Philharmonic. His daughter is principal violist with the Kansas City Symphony.

After 1968, Grossman saw and talked with the Beatles only sporadically. When Apple Corps was putting together a book about the group, Grossman was asked for some images. The fee offered was well below market rates, so he declined. He says, “I got a cable from George saying, ‘Henry, whatever happened to “Oh, what a beautiful morning?’” — a reference to the times Grossman would run on the beach in the Bahamas, belting out the opening song from “Oklahoma” — “‘Why can’t we use these pictures?’”

In 1974, Grossman says, he and Harrison reunited “like brothers” at a photo shoot, and he signed on to work as an official photographer for Harrison’s solo tour that year.

Since George’s death, Olivia Harrison has come by to have coffee with Grossman and look at photos of her late husband. “We’re in touch,” he says. “I speak with her every once in a while.”

Grossman bumped into Lennon and Yoko Ono once on a New York sidewalk, and they chatted for a few minutes. Even though Lennon lived near him, “I never wanted to call him up and ask for photographs, because I knew how much the Beatles had been besieged and how often,” Grossman says. “So I deliberately didn’t call him. Of course, now I’m sorry I didn’t.”

The months spent assembling and promoting “Places I Remember” have been an emotional journey for Grossman, a long and winding road back to a thrilling, simpler time. “Looking back on all the Beatles shots has given me great pleasure, like visiting old friends,” he says. “The Beatles were wonderfully bright and unique individually, and obviously even more so as a group. I admired them greatly. It was exciting and fun being with them. And I was trusted. They accepted me as a friend.

“As someone once said, ‘I am so grateful for all the gifts of this incarnation.’”