Like Fire and Powder

Henry Fuseli

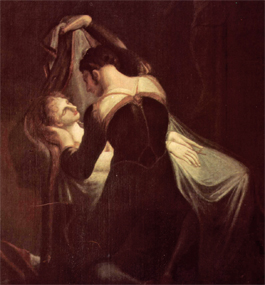

FAREWELL: Romeo discovers Juliet in her tomb.

by Laura Gardner, P'12

Long before the Elizabethan Age, Romeo and Giulietta were central characters in a popular Italian tale — doomed young lovers from feuding families in Verona, who end their lives in the consoling hope that their love will persist after death. At the story’s end, they lie together in a private tomb, an earthly symbol of the heavenly love they will forever share.

Enter William Shakespeare, who transformed this well-known narrative into one of the most powerful and persuasive declarations of love ever imagined, by putting more finality into the final act.

“Shakespeare rips apart the idea that Romeo and Juliet will have an erotic afterlife,” explains English professor Ramie Targoff. To emphasize this point, he deprives the young lovers of a private burial tomb. This departure from the story’s earlier versions signals a complete break with the poetic tradition of Dante and Petrarch, who imagined immortal love with their respective beloveds, Beatrice and Laura.

In “Romeo and Juliet,” Shakespeare “strips away any consolation from the end of the play,” Targoff says.

Even more profoundly, Shakespeare makes death “the full, explosive experience of love,” writes Targoff in her new book, “Posthumous Love: Eros and the Afterlife in Renaissance England” (University of Chicago Press, 2014). And in rejecting posthumous love, Shakespeare rendered earthly passion all the more potent and precious, by underscoring its transience.

A noted scholar of English Renaissance poetry, Targoff has long been fascinated by the relationship between religion and literature, particularly the Protestant Reformation’s fertilization of English literary and popular culture with new ideas, including the rejection of the concept of transcendent love. “Posthumous Love” looks at how notions of love became bound by mortality, and the effect that change in thinking has had on centuries of poetry.

The Protestant Reformation fundamentally altered the way people thought about the relationship between the living and the dead, Targoff says: “In the Protestant Church, widows and widowers were not encouraged to mourn excessively for their deceased spouse. They were prohibited from praying directly to the dead. And — if they were of child-bearing age — they were strongly encouraged to remarry.”

As a result, the idea of “till death do us part” came to dominate English culture — a practical philosophy, since a quarter of all marriages in England were remarriages. “The idea of maintaining erotic ties to a deceased spouse was not part of the culture’s ideology,” says Targoff.

Against this backdrop, she says, a new kind of lyric love poetry flourished in England from the 1530s to the 1660s, and Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet” was in the thick of it. If the play illustrates just how combustible love can be — as Friar Lawrence puts it, “like fire and powder” — it also depicts death as the final expression of love.

Richard Howard

Ramie Targoff

page 2 of 2

The ethos of carpe diem generated a body of creatively erotic verse that is still the ne plus ultra of love poetry, viewing death as “the looming threat against which to seize the day,” Targoff says.

“There is an incredible frankness about love in carpe diem poems like Marvell’s ‘To His Coy Mistress,’” she says. “The poetry is seductive and persuasive. It’s like hearing the voice of someone from 500 years ago making love to someone else, and the voice is raw, urgent. It’s so intimate — that’s what I love about it.”

Targoff calls the opening words of “To His Coy Mistress” — “Had we but world enough and time, / This coyness, lady, were no crime” — “one of the greatest lines of all times.” The poem’s speaker goes on to profess that, if he could, he would devote eons to studying his lady’s lovely face and figure: “An hundred years should go to praise / Thine eyes, and on thy forehead gaze; / Two hundred to adore each breast, / But thirty thousand to the rest.”

Yet life is short, the poem reminds us, so let the kissing commence. And who wouldn’t want to be seduced right now, given the inevitable end of love that Marvell envisions: “The grave’s a fine and private place, / But none, I think, do there embrace.”