Jousting With the Alt-Right

In a battle for diversity, open inquiry and historical truth, Dorothy Kim has thrown down the gauntlet to reimagine medieval studies for our time.

Anthony Crider / Wikimedia Commons

CHAOS AND HATE: Alt-right protesters carrying Nazi, Confederate and medieval symbols at the 2017 Charlottesville, Virginia, rally.

by Lawrence Goodman

In August 2017, Dorothy Kim, an assistant professor of English, watched in horror as news outlets covered the neo-Nazi and white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. Rally participants chanted “Jews will not replace us” and shouted the Nazi mantra “Blood and soil.” Violence injured 30 the first day of the rally. On the second day, a white supremacist drove a car into a crowd of counterprotesters, killing 32-year-old Heather Heyer and injuring 19 others.

Amid all the chaos, Kim noticed the medieval imagery. Shields were decorated with black eagles and sonnenrads, wheels with zigzagging spokes, a symbol from medieval Scandinavian culture. When demonstrators yelled “Deus vult,” which means “God wills it,” they were appropriating a Latin slogan used during the Crusades.

A few days after the rally, Kim, a scholar of medieval literature, wrote a blog post addressed to her fellow academics titled “Teaching Medieval Studies in a Time of White Supremacy.” She exhorted them to warn their students about the perversion of the history and iconography of the Middle Ages for political ends. Classroom lessons on the Hundred Years’ War, the rise of feudalism and Catholic theology needed to include discussions about the growing power of the global far-right movement, she said.

Within days, Reddit forums and Breitbart News were calling Kim a “notorious nut job,” a “committed communist” and someone who “hates the truth, which is that Europeans created the greatest culture.” These were some of the nicer things said.

More than two years later, Kim still keeps her email address private. But the online threats she received have not deterred her from leading an unlikely movement to bring medieval studies into the 21st century.

It’s a two-pronged effort, she says. She wants to inform the public about the alt-right’s “weaponization” of the Middle Ages. And she hopes to open up the historically insular field of medieval studies to new ways of thinking about race, inclusivity and equity.

Dark-skinned Orcs and Dothraki

Scholars say the Middle Ages, which spanned the fifth century to the 15th century, is fodder for the far right, which has hijacked its symbols and mythologized its narratives to promote hate and white nationalism.

The myth of chivalry inspires fanatical adherents to imagine themselves as heroes embarking on heroic quests. Vikings conjure up images of an idealized masculinity. The alt-right falsely believes the prohibitions and societal norms that govern us today didn’t yet exist in the Middle Ages. They see the medieval era as a time when out-of-bounds opinions and violence were permissible.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Ku Klux Klan insisted its members were knights battling the twin demons of Reconstruction and racial equality. Its leader was called the Imperial Wizard; his deputies were Grand Dragons.

The Nazis used medieval runes as symbols of their might and noble lineage. The SS officers who ran death camps used Nordic mythology for their initiation rites.

Today, the far-right British National Party runs a summer camp called Camp Excalibur, a reference to King Arthur’s legendary magical sword. Right-wing reactionaries in Brazil use “Deus vult” as their slogan. The editor of the U.S.-based neo-Nazi website and message board The Daily Stormer has said women should “remain in the exact same role they were in during the medieval period.”

In a Time essay published last April, Kim mentions the Viking references that appear in a manifesto written by the white supremacist gunman who killed 51 people in two mosques in New Zealand in March 2019. The guns the killer used were decorated with multiple references to medieval battles and the Crusades. “But far-right Viking medievalism is not about historical accuracy,” Kim writes. “Rather, it’s used to create narratives […] that activate violent hate.”

Kim, who immigrated with her parents to the U.S. from South Korea as a young child, says reactionaries share a view of medieval Europe as a stronghold of white people battling hordes of dark-skinned invaders. This view, she says, is at least partly fueled by popular culture.

WHITE MIGHT: In the “Game of Thrones” TV series, the swarthy Dothraki are led by the very pale-skinned actor Emilia Clarke.

page 2 of 4

In the “Lord of the Rings” series, members of the Uruk-Hai, a breed of Orcs, are described as dark-skinned, as are other followers of the evil Sauron. In the HBO series “Game of Thrones,” the dark-skinned Dothraki are barbarians led by a white woman, the very pale-skinned actor Emilia Clarke, whose hair is bleached platinum blonde for extra measure.

The belief in a white medieval Europe is so hard to shake that when the BBC cast a dark-skinned actor in the role of Guinevere for its show “Merlin,” fans — who didn’t blink an eye at the sorcery or the dragons — protested the choice as historically inaccurate.

In fact, medieval Europe was no bastion of whiteness. The Iberian Peninsula was inhabited by Arabs. Sub-Saharan Africans regularly came to Europe to trade, explore or wage war. Excavations in London recently uncovered a Black Death cemetery in which at least 20% of the bodies were either Muslim and/or African, suggesting that people of color, either as slaves or traders, were far more present in England than previously imagined.

In her blog post about Charlottesville, Kim urged her fellow medievalists not to retreat into the ivory tower but to dispel white supremacists’ myths and lies about the Middle Ages. “Choose a side,” she wrote. “Doing nothing is choosing a side. Denial is choosing a side. […] Neutrality is not optional.”

Though many medievalists already believe they have a responsibility to engage with a broader audience, Kim went further: She accused her field of propagating the myth of a white medieval Europe, writing, “Let us be crystal clear here — medieval studies is intimately entwined with white supremacy and has been so for a long time.”

Like putting a wanted poster on the internet

Almost as soon as the Middle Ages ended, scholars and thinkers began co-opting the era for their own political ends.

Universities first arose during the medieval period. Law, the arts and even the sciences advanced considerably. International trade brought cultural exchange, and the spread of wealth and knowledge. Yet the 14th-century Italian poet Petrarch called the Middle Ages a lapse into darkness after the “light” of classical antiquity’s great learning and wisdom. Petrarch took potshots at the Catholic Church to champion the Early Renaissance — his era — above all others. Four hundred years later, Enlightenment philosophers did the same, coining the term “the Dark Ages” to make the put-down official.

Nineteenth-century historians embraced the Middle Ages to promote nationalism. They identified racial, cultural and intellectual traits in medieval people that supposedly gave rise to the unique characteristics of the European states. They said the Crusades civilized and enlightened the Middle East, justifying further European expansion and imperialism. By the 1920s, German academics were pointing to the eastern expansion of the medieval Reich to legitimize Adolf Hitler’s pursuit of Lebensraum.

Kim believes her field has still not confronted its past. As a result, a legacy of bias and prejudice persists in subtle and overt ways. Like other medievalists of her generation, she wants her colleagues to examine how their research continues to privilege white men and white narratives about the world to the exclusion of all others. Kim says medieval studies has no choice — it has to change.

Medieval studies has long been an insular field. In the 1990s, many humanities disciplines went through a period of intense introspection. Academics developed new research approaches that considered race, gender, sexuality and class. Efforts were made to increase diversity among scholars and subjects. But medieval studies “just ignored what was going on in society and what was happening in other disciplines,” Kim says.

Kim’s father is a retired car mechanic, and her mother is a housewife; the family has been Catholic since the 18th century. Kim was the first in her family to go to college. As an undergrad at the University of California, Berkeley, and a doctoral student at UCLA, she often felt like an outsider. Being Asian American in a field where less than 1% of scholars are people of color heightened her sense of alienation.

A few weeks after Kim wrote about Charlottesville, Rachel Fulton Brown, an associate professor of history at the University of Chicago, offered a response. Fulton Brown studies religious practices and prayer during the Middle Ages, with a special emphasis on the role of the Virgin Mary. She’s written three books, the first of which won several prestigious awards, and she received a 2008 Guggenheim fellowship. A self-described conservative, she battles what she sees as the forces of political correctness.

Kim “wants you to be afraid,” Fulton Brown wrote in a blog post of her own. She called Kim’s charges against medieval studies indiscriminate and said they were meant to pressure scholars to “cleanse ourselves and our academic subject of this stain [...] or else!”

Fulton Brown also said people during the Middle Ages cared more about Christianity than they did race. She cited examples where the Virgin Mary was described or depicted as dark-skinned.

It didn’t end there. Fulton Brown shared her post on Facebook with her friend Milo Yiannopoulos. Yiannopoulos, an alt-right provocateur, has been widely condemned as a misogynist, white nationalist and antisemite. His “Dangerous Faggot Tour” of college campuses set off protests, including one at Berkeley that turned violent.

Yiannopoulos responded with his own post, titled “Lady With a Sword Beats Down Fake Scholar With Facts and Fury,” the lady being Fulton Brown and the fake scholar Kim. Though he’s since been banned from Facebook, Yiannopoulos then had nearly 2 million followers, eager and primed to take up his anti-Kim crusade.

Mike Lovett

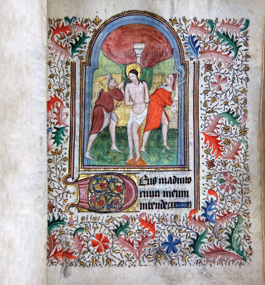

CREATING THE “OTHER”: An illustration of Jews assailing Jesus, from a 15th-century French prayer book in the Goldfarb Library archives.

page 3 of 4

It was as though someone had put up a wanted poster of her on the internet, asserts Kim, who was teaching at Vassar at the time. The alt-right specializes in using online discussion groups, news sites’ comments sections and social media to rile its followers into harassing and intimidating others. The targets of their ire have seen pictures of their families and their home addresses posted online. But “they don’t actually need to do this to you,” Kim says. “Knowing they are capable of it is enough to instill fear.”

Kim’s fellow scholars rallied around her. Some 1,300 academics signed an open letter to the University of Chicago’s history department, saying Fulton Brown’s writings and online activity had “expose[d] Professor Kim to one of the most racially violent contingents currently operating.”

The University of Chicago issued a statement defending Fulton Brown’s right to free speech and the expression of her opinions. Fulton Brown declined to comment for this article but, in an email, wrote that her position is laid out on her blog and in Yiannopoulos’ 2019 book, “Middle Rages: Why the Battle for Medieval Studies Matters to America.”

In his book, Yiannopoulos praises Fulton Brown and attacks Kim. “Leftist critiques of the field [of medieval studies] seem to have less to do with rebalancing a Euro-centric understanding of the past than they do with giving white Christian Europe — and, by implication, modern Christian America — a bad name,” he writes.

A modern clash over race

On a late-fall day, Kim stands in the Goldfarb Library archives examining an illustration of two Jews with big noses in a 15th-century French prayer book. It’s part of a flagellation of Christ scene, in which Jesus is tied up and whipped by his tormentors.

In this version, Christ is against a white pillar and has a golden halo. The setting is European pastoral, not the Holy Land. The Jews don’t flog Jesus so much as they point toward him and give him nasty looks. “Whoa, that’s a lot of leg,” Kim says, pointing to the exposed thighs and knees of the Jewish men, who are drawn with their tunics hitched up. Naked lower limbs were a symbol of male oversexualization, she says.

Prayer books — or books of hours, as they were known — were expensive to produce and were largely custom-made for upper-class women, who often carried them everywhere. This book is in such excellent shape that Kim suspects it remained at home. Its pages are vellum, likely made from calves’ skin. The ink for the filigree that surrounds the drawing came from exotic locales — blue from lapis lazuli in Afghanistan, vermillion from Africa.

Scholars consider exaggerated depictions of Jews, like the one in this book of hours, antisemitic. Kim and her generation of medievalists argue they also mark the beginning of European racism. Jews weren’t just singled out for their religious beliefs but also for physical characteristics imagined to be rooted in their biology. Until the 13th century, Jews weren’t depicted in Western art with distinguishing, racialized features. Then they began to be portrayed with horns and tails, and exaggerated and misshapen noses and beards. Jewish men were believed to menstruate. Both sexes supposedly enjoyed drinking gentile blood. All these myths were meant to stoke hatred.

Countries organized bureaucracies to regulate and control Jewish people. In England, the monarchy created the Exchequer of the Jews, a department that required Jews to register so the state could monitor their movements. Across Europe, laws governed how Jews ate (never with Christians) and what they wore (special hats and clothing of a particular color). The Catholic Church required Jews to wear badges so they could be differentiated from Christians at a glance. English Jews wore on their breast a piece of yellow felt in the form of the Ten Commandments tablets.

Kim says these practices were a harbinger of the racial policies adopted by Nazi Germany in the 1930s and ’40s. It was about marking the bodies of Jews as “other” — something grotesque, dangerous and diseased. According to Kim, European racism against blacks, equally rooted in false beliefs about human biology, also originated during the same period.

When Kim and researchers like Geraldine Heng, a professor and scholar at the University of Texas at Austin, started discussing race, more-senior medievalists balked. They argued that racial categories originated later, during the Renaissance, that the term “race” didn’t even exist in the Middle Ages.

Kim believes the opposition to considering race is part of medieval studies’ “whiteness” problem. White professors, she asserts, have difficulty recognizing racism because they don’t understand what it’s like to experience it.

Academics are still debating how people thought about race during the Middle Ages and how ethnicity or religion was viewed. The distinctions between racial and ethnic categories can be blurry. But the medieval studies field is gradually shifting, and scholars are beginning to discuss what racial categories existed in medieval times.

The acknowledgment has led to a wider evaluation of the Middle Ages that’s made the era much harder to idealize, helping to debunk white supremacist theories and turning our understanding of the period on its head. “A lot of the terrible, horrific things that have happened in the last several centuries — and that we’re still dealing with — were worked out and refined during the Middle Ages,” Kim says.

Mike Lovett

Dorothy Kim

page 4 of 4

As a result, the field of medieval studies is in tumult. At the 2019 meeting of the International Society of Anglo-Saxonists, a huge controversy erupted over whether to strike “Anglo-Saxon” from the organization’s name. White supremacists have long used the term to describe what they view as a superior race and culture. By continuing to use it, would the group of scholars be perpetuating a racist phrase?

“Why would you want to carry around a bag with ‘Anglo-Saxonist’ written on it?” Kim says, referring to the swag given away at the meeting. “It’s embarrassing.”

The group eventually voted to change its name to the International Society for the Study of Early Medieval England, but not before one of its leaders resigned in disgust over many issues, including the hesitancy of many members to acknowledge the racism she believes is inherent in “Anglo-Saxon.”

Kim’s first book, “Jewish/Christian Entanglements: Ancrene Wisse and Its Material Worlds,” will soon be published by the University of Toronto Press. Ancrene Wisse, written in the early 13th century and popular in England, was a kind of how-to manual for a group of mostly female religious ascetics known as anchorites. After passing through a ritual that rendered her officially dead, an anchorite would live in a 12-square-foot chamber that was completely sealed except for a small window through which she could receive food and dispense of waste.

Despite their apparent seclusion, the anchorites actually interacted extensively with the surrounding community, including its Jews, Kim argues. She sees in Ancrene Wisse examples of Talmudic reasoning, which the anchorites used to develop their religious belief system. For all their antisemitism, it seems the anchorites used Jews and Jewish religious material to bolster anchoritic authority.

Meanwhile, the group Medievalists of Color, of which Kim is a steering-committee member, has been pushing for more study of ideas about race during the Middle Ages and racism within the profession itself. Kim helped coordinate and lead Whiteness in Medieval Studies workshops at the 2017 and 2018 meetings of the International Congress on Medieval Studies. She recently wrote a paper with M.W. Bychowski, a trans woman who is a medievalist at Case Western Reserve University, on making medieval studies more open to trans, nonbinary and intersex scholars. Kim and Brandeis classical studies chair Joel Christensen ’01, MA’01, are organizing a September conference, “Race Before Race: Politics,” co-sponsored by Brandeis and the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, bringing together antiquity, medieval and early-modern scholars for an examination of race in their disciplines.

And so Kim continues her fight against the alt-right and those in medieval studies who resist change. “A lot of people have said, ‘You’re so brave,’” she says. “But it’s not about bravery. It’s about survival. If we don’t deal with this, as far as medieval studies goes it will be a whiteout forever.”