A Magical Vanishing Act

Whether she’s playing a drunken gun-toting frontierswoman or an intelligent, intuitive therapist, actor Robin Weigert ’91 finds her characters by losing herself in them.

Jörg Meyer

Robin Weigert

by Lawrence Goodman

In 2001, Robin Weigert ’91 performed with Meryl Streep in a Mike Nichols production of the Anton Chekhov play “The Seagull” in Central Park. Weigert played Masha, the depressive farmer’s daughter, whose love goes unrequited and who resigns herself to a meaningless existence.

After Weigert appeared in her first performance, Streep slipped her a postcard thanking her for her “love and support that has sustained me through [rehearsals].” It also included a prediction: “Wonderful things are in store for you. Mama knows.” (Streep’s character, Arkadina, was the matriarch of the play. The actor may also have been making playful reference to her status as American theater and film’s reigning matriarch.)

For Weigert, still at the beginning of her career, Streep’s note was “a beautiful gift. I felt seen in the potential that I hoped with all my heart to realize.” She framed the postcard and hung it on her apartment wall.

Streep was the very reason Weigert became an actor. At 12, she was mesmerized by Streep’s performance in “Sophie’s Choice,” she says, because Streep “vanished so utterly into her character. It was so complete.” Like Streep, Weigert is a character actor, finding her characters’ unique idiosyncrasies without sacrificing their humanity, uncovering the full sweep of their emotional complexity and inner contradictions.

In 2004, Weigert received an Emmy nomination for her depiction of the dirt-smeared, growling frontierswoman Calamity Jane, whose belligerent temper never completely masks her tenderness, in the HBO series “Deadwood.”

She went on to play the lead in the 2013 indie movie “Concussion,” locating in her character’s suburban-wife restlessness the makings of a high-class call girl, earning raves and proving she could hold her own as a feature film star. A critic called her “one of America’s most overlooked actresses.” By all accounts, Streep’s prediction was coming true.

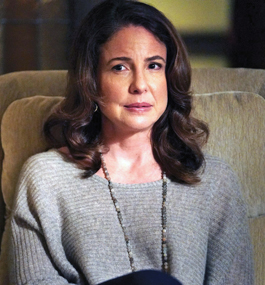

By 2017, she had landed the role of Dr. Amanda Reisman, the therapist on the HBO series “Big Little Lies,” which became a huge hit for the network.

Weigert loses herself in her roles. Playing a motorcycle gang’s savvy lawyer in FX’s “Sons of Anarchy”; a jilted wife who turns murderous in “Marvel’s Jessica Jones”; or a neurotic, panophobic roommate in the film “Pushing Dead,” she burrows to the point of self-erasure.

“That kind of vanishing, letting a character take you over, join you and work inside you — it’s almost a mystical experience,” she says.

Setting the stage

In July, Weigert came to northern Massachusetts to film an episode of “Castle Rock,” Hulu’s Stephen King-inspired psychological horror series. When she steps out of an elevator at a Tewksbury hotel, wearing bell-bottom jeans and a light summer blouse, she exudes a casual elegance, possessing what a critic has described as an “intriguing, indistinct beauty.”

She looks — and sounds — nothing like Calamity Jane. During the “Deadwood” years, she says, the gym was where she was most frequently recognized, when she was at her sweatiest.

Weigert, who splits her time between West Hollywood and New York, picks at a salad and sips kombucha at Life Alive, a Lowell, Massachusetts, vegetarian restaurant (“It has a very LA vibe,” she observes). When she talks, she looks into the distance, deep in thought. Her sentences emerge elegant and perfectly formed, flowing seamlessly one after the other, giving rise to complete ideas and insights.

Her grandmother Edith Weigert was a pioneering psychoanalyst in Germany during the 1920s and ’30s, one of the few women in the profession. Edith and her Jewish husband, Oscar, who worked in unemployment law, were forced to leave the country when Adolf Hitler took power. They moved to Ankara, Turkey, where Oscar worked with Kemal Atatürk, the Republic of Turkey’s founder and first president, to modernize the country’s labor laws.

Courtesy HBO

CRAZY HEART: As Calamity Jane in “Deadwood,” Weigert is a coarse, grubby soul of compassion.

page 2 of 4

Unable to establish a practice in Ankara, where Freudianism was not widely embraced, Edith moved to the U.S. in 1938, where she was joined by Oscar and their 6-year-old son, Wolfgang, Robin’s future father.

Wolfgang became “Walter” in America; married Dionne Laufman, a prize-winning concert pianist; and settled in Washington, D.C., where he practiced psychiatry in the same city where his mother was chair of the Washington-Baltimore Psychoanalytic Institute and a faculty member at the Washington School of Psychiatry.

Weigert and her older brother, David, attended the prestigious Sidwell Friends School, where she first started acting. She played the forlorn, not-too-bright Miss Adelaide in a production of “Guys and Dolls.” With a “New York accent that could cut rocks, and a wildly expressive face, she dominated several scenes and stole the show,” the student newspaper reported.

Though Weigert occasionally thought about going into her father and grandmother’s profession, high-school theater thrilled her, and she officially caught the acting bug.

She was an A student at Brandeis. In a class taught by poet Allen Grossman, PhD’60, she fell in love with Rilke, Freud and Yeats. “Theater is the enemy of the mind,” Grossman told her. She wasn’t sure whether this was a warning or a challenge — it was Grossman’s rhetorical style to pose unanswerable questions like “Do the words make the worlds, or do the worlds make the words?” — but she admired him, and his pronouncement made her wonder whether she should take acting seriously.

Weigert performed in Brandeis productions of “Fiddler on the Roof” and “Yentl,” and worked with directors Danny Gidron ’66, MFA’68, and Ted Kazanoff (who also taught Tony Goldwyn ’82 and Debra Messing ’90). Both men told her she had immense talent. In her senior year, Weigert decided she would apply to three top acting schools. If she was rejected by all of them, it would be a sign she should choose another career.

She was accepted at NYU. The only real challenge after that was taking her acting calling seriously.

Channeling her inner child

In 1953, Doris Day starred as Calamity Jane in an eponymous Warner Brothers musical comedy. In the film, Jane is a rough-and-tumble shotgun messenger when she comes to Deadwood, Dakota Territory. Handy with a pistol and always up for a musical number, she proves her mettle in a man’s world mainly by killing Native Americans. This Jane is a feminist in the classic 1950s Hollywood mold: tough and rebellious at the start, doe-eyed and weak-kneed as soon as her love interest arrives.

The real Calamity Jane was a quintessentially American character: a huckster who spun tall tales about her heroic deeds; a down-and-out alcoholic; a protofeminist who wore men’s clothes and carried a rifle; a compassionate soul who, in the midst of Deadwood’s smallpox epidemic, cared for the sick and dying.

In her 2002 audition for the “Deadwood” role, Weigert played Jane with a deep voice and a tough-guy persona. She had so little television experience, just a single episode of “Law & Order,” that she didn’t expect to be called back. A few months later, she got that call. This time, she dressed up in a cowboy costume, complete with chaps, a fringed vest and a hat. “I wanted to show them I could play a badass,” she says.

When Weigert was ultimately cast, the show’s producers told her it was because they liked how vulnerable she made Jane — the exact opposite of what she had intended. That underlying softness she inadvertently found would make her performance remarkable. Though her Jane is every bit as depraved, coarse and bellicose as the men in Deadwood, deep down she craves human connection.

A tomboy and a loner growing up (“It’s fair to say I was troubled but sweet,” Weigert says), she channeled her inner child into Jane. “I tapped into a part of myself that I’ve essentially outgrown,” she says. “There’s no other way as an adult I can manifest the side of myself that’s manifest in her. I miss her the most of any character I’ve played.”

Courtesy HBO

COUCH WORK: Weigert’s Dr. Amanda Reisman functions as the calm, present center of “Big Little Lies.”

page 3 of 4

Over the course of the show, Weigert learned to spin a gun and crack a bullwhip. She also developed a unique bond with David Milch, the show’s creator. Milch’s “Deadwood” dialogue is famously gnarly. Full of baroque sentences, laden with curses and shocking sexual imagery yet somehow lyrical, it’s David Mamet meets Shakespeare.

From time to time, Milch invented lines for Weigert on set, with the script supervisor jotting them down as he spoke them. Weigert absorbed Milch’s speech patterns and movements when he embodied Jane, and integrated them into her performance.

In a Season 1 episode, in a typical drunken stupor, Jane falls off her horse, landing on the ground on her back with her foot caught in a stirrup. She plays it off as a temporary setback, announcing, “This happens to be a rig and contraption of my own devising against repeated accidental falls that has temporarily malfunctioned.” Weigert’s slurred delivery renders Jane pathetic and comic, yet evokes our deep sympathy for her.

After three seasons, “Deadwood” was canceled in 2006. HBO and co-producer Paramount couldn’t agree on terms for additional episodes. Milch called Weigert, who had just bought an apartment in New York and was taking a walk in Central Park, to tell her the news. “It was the first time in my life I had a little stability,” she says. “Then, suddenly, everything felt wide open and unsupported.”

In 2019, HBO premiered “Deadwood: The Movie,” which wrapped up the plotlines left unresolved when the series abruptly ended. Ten years have passed. South Dakota is becoming a state, and Calamity Jane is pursuing a romantic interest Doris Day could never have imagined — another woman. By the movie’s end, Jane has become an unlikely hero, the rebel and outcast who, despite herself, helps the town preserve law and order.

The most important thing that had changed since the series went off the air was Milch’s health: He’d been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. Making the movie was both wrenching and special for the cast and crew. “The wish to honor David was so deep, the wish to honor what he had created,” Weigert says. “It was really a beautiful experience.”

‘I told you, I told you, I told you’

Playing therapist Amanda Reisman in “Big Little Lies” came a lot easier than playing Jane.

Weigert says the scenes set in Dr. Reisman’s office are meant to capture the rhythms of a real therapy session. In fact, a 2017 story in New York magazine quoted real-life therapists cheering that — at last — Hollywood had portrayed therapy accurately.

Reisman’s scenes with Celeste, a domestic violence victim played by Nicole Kidman, “are spellbinding, easily the most compelling part of the show,” the magazine said. Pauses, silences, going over the same material again and again — Weigert and Kidman turn the awkwardness of analysis into dramatic devices that heighten the tension and subtext.

And, in much the same way analyst and analysand adapt to and even transform the other, Weigert and Kidman play off each other, keenly attentive to the other’s dialogue and body language. “Acting is all about listening, similar to being a therapist,” Weigert says. “You’re listening the other character into existence. They are listening you into existence. It’s a compact where you’re both brought into existence by the other.”

Reisman’s goal is to get Celeste “to wake up, not sleepwalk into disaster,” Weigert says. The therapist needs to lead the troubled woman to the self-awareness that she’s in a toxic relationship, finding a balance between outright telling Celeste to leave her abusive husband and letting her figure out why she continues to stay.

While filming Season 2 of “Big Little Lies,” which aired in 2019, Weigert reconnected with Streep for the first time since 2002, when both actors were at a table read for the Mike Nichols-directed HBO production of “Angels in America.” Called to the set for a hair consultation just as Kidman and Streep were finishing up a scene, Weigert waved shyly at Streep when their eyes met, hoping for a moment of recognition but in no way prepared for what was to follow. Streep came over to Weigert and embraced her, reminding her of the “wonderful things” prediction, now come true. “I told you, I told you, I told you,” Streep said.

Joan Marcus

WINGED DESCENT: Weigert played the angel in the 2010 off-Broadway production of “Angels in America.”

page 4 of 4

Last summer, Weigert put the finishing touches on a short film, “The Truth About Animals,” which marks her debut as a director. She prepared for directing by watching classic films like “Casablanca” with the sound off to develop a better understanding of visual storytelling. In the best old films, she says, you don’t even need to hear the dialogue. “Films were directed in an almost pageant-like way,” she says. “You can see exactly what is happening.” Throughout the shooting and editing process, she also sought advice from various director friends of hers, including Jay Roach, whom Weigert met while playing the role of civil rights attorney Nancy Erika Smith in the movie “Bombshell,” about the sexual harassment scandal at Fox News.

Written by playwright Nastaran Ahmadi, “The Truth About Animals” is loosely based on a dinner-table conversation Weigert overheard as a kid. Her mother, who was preparing to perform a composition written by an 8-year-old musical prodigy, invited the boy and his parents over for dinner. The boy’s mother declared she thought her son was the reincarnation of a Holocaust survivor. She said he’d suddenly started talking in German and recounting a past life while she was giving him a bath, well before he’d learned many words in English.

Weigert says this “tremendously creepy but fascinating” conversation stayed with her. She talked about it with Ahmadi, who felt it could be the foundation for a good short film.

“We set out to tell a story about a family who cannot agree on what’s real,” says Weigert. “Both parents love their child but vehemently disagree about the source of his ‘condition.’ Since a fundamental disagreement about the nature of reality is the basis of our current national crisis, it seemed like a good moment to tell a story about how challenging it is to love when we cannot agree on the truth.”

Weigert doesn’t know yet whether “Big Little Lies” will be renewed for another season. She hopes it is. “We could do a whole season based on where we left off,” she says. “It would be quite interesting.”

Since the series first aired, her life has changed significantly. She’s recognized in public. She has a small but devoted following online. “I would marry Weigert in an instant,” a fan wrote on YouTube. “I’m in awe of her genius.”

The attention makes Weigert nervous — she didn’t become an actor to find fame. “People want to see actors play versions of themselves,” she says. “That’s not interesting to me. I love transforming. Something takes you over when you play a role you were meant to play.

“It doesn’t always happen. But when it does, it’s magic.”