‘Their Great Soul-Hungering Desire Was Freedom’

African Americans living in Civil War refugee camps imagined a new future for themselves from the ashes of slavery.

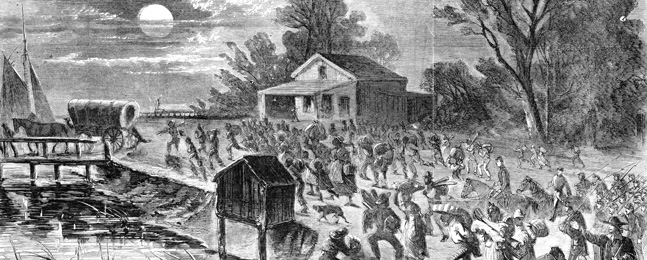

Courtesy Library of Congress

FLIGHT OUT OF BONDAGE: An 1861 illustration shows African American families, carrying their possessions, racing toward a bridge that leads to Fort Monroe, a Union redoubt in Virginia.

by Lawrence Goodman

Mary Armstrong was born into slavery on a farm near St. Louis, Missouri. At the end of her life, she told an interviewer that her owners were “the meanest two white folks who ever lived.”

The master, William Cleveland, Armstrong remembered, used to “chain slaves up to whip ’em, and rub salt and pepper on him, like he said, ‘to season him up.’” When he sold a slave, “he’d grease their mouth all up to make it look like they’d been fed good, and was strong and healthy.” (Interview transcribers attempted to capture Armstrong’s words as spoken.)

Cleveland traded Armstrong’s mother to another owner in Texas when Armstrong was young. Cleveland’s wife, Polly, whipped Armstrong’s 9-month-old sister to death. She tried to do the same to Armstrong, but Armstrong threw a rock at her eye and sent her off, howling in pain.

When she was about 17, Armstrong was set free by her new owners, Polly Cleveland’s daughter and son-in-law. It was 1863, two years into the Civil War.

Armstrong made an almost unimaginable decision — she headed south into the heart of battle, where, as far as the Confederacy was concerned, slavery remained legal. She carried only a basket of food and a basket of clothing when she set out by steamboat to New Orleans. From there, she went to Texas, first by boat to Galveston and Houston, then by stagecoach to Austin. “My back busted sure enough. It was such rough ridin’,” she recalled.

Soon after disembarking in Austin, Armstrong was captured and put up for auction. About to be handed over to her new owner, she pulled out the papers showing she’d been freed. A state official, apparently still respectful of the law, inspected the documents. “This gal is free and has papers,” he said, according to Armstrong, and set her loose.

After roughly two more years of working and saving money, Armstrong ended up some 150 miles south of Austin, in Wharton, where hundreds of African Americans gathered in a refugee camp to wait out the war. Here, Armstrong found what she’d been looking for all along — her long-lost mother.

Armstrong later trained to be a nurse, saving numerous lives in the Houston area during a yellow-fever outbreak in the 1870s. When she was interviewed, she was 91. “My mind, jes’ like my legs, jes’ kinda hobble ’round a bit,” she said. But she hadn’t forgotten that joyous moment of reunion at the refugee camp. “Lawd me, talk ’bout cryin’ and singin’ and cryin’ some more,” she said. “We sure done it.”

Abigail Cooper, assistant professor of history, discovered Armstrong’s story a decade ago while writing her dissertation. Her adviser, historian Stephanie McCurry, had suggested she research the Civil War-era refugee camps set up by the North to house Blacks fleeing enslavement or the Confederate Army.

In the past, historians examined the camps from the top down, focusing on how the Union government administered and managed the Blacks liberated when the Union Army took over Southern territory. Cooper chose to research the camps from the perspective of the inhabitants themselves. What did they experience? How did they pray together? What did they learn in school? Most important, how did they imagine their future as free men and women?

“I wanted to look at how marginalized communities worked together to create something new, how they made a way for themselves outside a white master’s grasp,” says Cooper, now at work on a book about the refugee camps.

Mary Armstrong’s description of the camps was collected in the 1930s by the New Deal’s Federal Writers’ Project as part of an effort to record former enslaved peoples’ experiences. Cooper found other camp accounts in memoirs by Black writers and missionary accounts.

Taken together, these narratives show how vital and vibrant camp life could be. During a period of incredible uncertainty yet great ferment, the formerly enslaved redefined who they were as a people, and reinvigorated Black culture and religion. They began building a new future for themselves out of the ashes of slavery.

“By looking at this in-between moment, when slavery’s end was possible but not assured, we can see how African Americans made and lived out freedom on their own terms,” says Cooper. “African Americans gathered to forge a monumental psychological transformation, from knowing America as their enslaver to envisioning America as their home.”

From slavery to Slabtown

Cooper has documented more than 250 camps, through which roughly 800,000 African Americans passed during the war or shortly thereafter. The first camp was erected in Virginia in 1861. Camps quickly spread up and down the Eastern Seaboard, along the Mississippi River, and as far west as Kansas and Texas. Washington, D.C., which officially abolished slavery in 1862, three years before the war ended, had 22 camps within or just outside its boundaries.

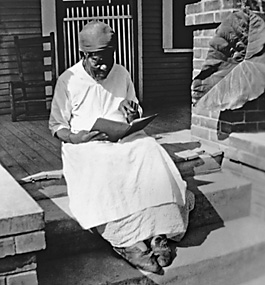

Courtesy Library of Congress

SHARING HER STORY: Former slave Mary Armstrong, in a portrait taken in Houston by a Works Progress Administration photographer in 1937.

page 2 of 4

Some Blacks went to the camps to find relatives; most came because they were a safe haven. Because Black men joined or were conscripted into the Union Army, camp residents were mostly women and children. Part of Cooper’s purpose in telling the camps’ story is to emphasize the central role Black women played in charting African Americans’ path forward.

The camps were squalid, ridden with famine and diseases like measles, typhus, smallpox and cholera. Overcrowded barracks or military-issued fabric tents housed people by the hundreds, sometimes thousands. The former enslaved people lived in constant fear of raids by Southerners who would kidnap them and sell them back into slavery.

Some white war refugees also lived in the camps. They were treated differently. A rations list Cooper discovered for a New Bern, North Carolina, camp shows that 1,800 whites received 76.5 barrels of flour over the course of three months in 1862-63. During the same period, the 7,500 blacks there received 19 barrels.

Despite these circumstances, African Americans achieved something extraordinary. Cooper’s research documents how they strengthened familial ties, acquired literacy and revitalized their religion. They became farmers, fishermen or merchants selling food to the Union Army — for many, this was the first time they’d ever been their own bosses.

In May 1861, just over a month into the war, three enslaved people in southeastern Virginia — Frank Baker, Shepard Mallory and James Townsend — learned their owner was moving them south, away from their families, to labor for the Confederate Army. Rather than obey, they sought refuge at nearby Fort Monroe, a Union redoubt in Confederate Virginia.

Perhaps out of sympathy, or maybe just to deny Southerners their enslaved people, the fort’s commander, Benjamin Butler, decided to take them in. His legal justification — which would have revolutionary consequences — was that if enslaved people were property, they could be legally confiscated by the North. Henceforth, African Americans who found shelter with the Northern Army were called “contraband,” and refugee camps would become known as “contraband camps.”

Within a few weeks, there were more than 900 enslaved people living at Fort Monroe. A few months later, Confederate soldiers rampaged through Hampton, just across the Chesapeake Bay from the fort. Though they set the city ablaze, they failed to hold it. Whites fled. Blacks remained. More Black refugees flooded in from elsewhere. They found doors, bricks and wood amid the ashes to build a settlement they nicknamed Slabtown, for the rough pieces of lumber they used for the makeshift huts and houses.

Lewis Lockwood, a missionary from New York, noted how the freedpeople converted a courthouse with only its walls left standing into a church and a school. “It seems that this place, where injustice had been sanctioned by law, should be converted into a sanctuary of justice, righteousness and free education,” he wrote in his memoir.

Union officials hired Slabtown’s residents to build defenses, cook meals for the troops and work in the hospitals, and paid them wages (though the money was less than what whites were earning). Blacks fished, gathered oysters from the bay and farmed the land their former enslavers had abandoned. Mary Peake, a freedwoman from Norfolk, taught reading, writing and arithmetic, and organized a Christmas celebration at which congregants sang religious songs and “My Country, ’Tis of Thee.”

By the end of the war, there were more than 10,000 Blacks living in or around Slabtown. According to Cooper, its success and the success of other refugee camps laid the foundation for future Black communities. Slabtown is now the site of Hampton University, one of the nation’s premier historically Black educational institutions. (Brandeis is currently collaborating with Hampton on scientific research, as well as an effort to bring more underrepresented students into STEM fields.)

“More than anything,” Cooper writes in her dissertation, “we should make careful study of the remarkable amount of resourcefulness it took for refugee slaves to gather their families into Union lines, to build information networks, to pray, eat, hoe, sing, give birth, share living space, take care of each other’s children, to imagine home while in a place outside a ‘household.’”

‘Sacred spaces of radical possibility’

After college, Cooper worked for Mississippi Cultural Crossroads, a nonprofit arts agency in Port Gibson, a low-income and majority-Black town in the southwest of Mississippi. In the after-school program she taught, she encouraged students to improvise scenes from their everyday lives as a way of creating theater. In these scenes, a rich religious world came into view. Students interspersed references to Jesus and the Bible with rap lyrics and talk about local personalities. In the students’ narration, civil rights advances would have been impossible without God’s will, without their churches.

Courtesy Library of Congress

RISING FROM RUBBLE: An 1864 photograph of Slabtown, a refugee settlement in Hampton, Virginia.

page 3 of 4

It took a while for Cooper, recently graduated from New York’s Barnard College, to understand fully the form and function of the religious worlds she witnessed in these students’ self-made theater. In this deeply spiritual Black community, religion was intertwined with culture, the arts and politics. More often, religion was culture, the arts and politics. Although history scholars tended to see religion as peripheral to the action of freedom, Cooper realized she needed to keep in mind the voices that many had discarded because they were religious.

Likewise, when Cooper began reading accounts of life in the refugee camps, she was struck by the extensive descriptions of religious activities. Prayer took place at all hours, especially in the middle of the night. The former enslaved people continually rejoiced over their new freedom and, as disease and starvation spread, lamented for the dead. Cooper realized that religion served a similar function in the camps as it did in Port Gibson. It was a way for the former enslaved people to discuss politics and society. It provided the language they used to define what it meant to be free men and women in America.

“Most slaves would have described many of their struggles for power as religious, not political,” Cooper writes in her dissertation. Through religion, the camps became “incubators of revolutionary revival” and “sacred spaces of radical possibility.”

Toward this end, Bible groups sprang up in the camps. Blacks went to them to learn to read and interpret Scripture. The Exodus story became a parable for their own plight: Egypt was the slave-owning South; the camps, the desert and Jericho were the America where they would be free. Drawing on the idea of the day of jubilee in the Book of Leviticus, when the Hebrew slaves would supposedly be freed, African Americans celebrated the Emancipation Jubilee, which commemorated Jan. 1, 1863, the date the Emancipation Proclamation officially took effect.

African Americans in the camps also developed new rituals for funerals and other religious practices. In what were called “watch meetings” (also known as “watch-night meetings” or “setting up”), Blacks danced, clapped, prayed and experienced ecstatic visions for hours on end to honor the dead. For the most part, these were joyous, liberating experiences; dying in freedom was preferable to dying in slavery.

Such prayer sessions, Cooper says, were actually an “effort to bring about emancipation.” She quotes an interview conducted by the Federal Writers’ Project with the formerly enslaved Mary Gladdy: “The slaves would sing, pray and relate experiences all night long. Their great soul-hungering desire was freedom.”

In her dissertation, Cooper cites an instance where a mourning mother expressed some relief after three of her children died in a camp. At least she knew where they were buried and could mourn them. If the family had been enslaved, the children might have been sold to another owner, and she would have never seen them again.

Archaeological digs at former refugee camps have turned up another aspect of the refugees’ religious practices — links to Africa. Researchers have found crosses, furniture and coins inscribed with geometric cosmograms unique to the Kongo people, a Bantu ethnic group of Central Africa. And they’ve discovered buttons originally thought to have been used for clothing, but, since other sewing materials have not been found, it’s more likely the buttons were charms, used to continue African traditions.

Similar artifacts have been found at sites on America’s Atlantic coast, and as far inland as Kentucky and Texas. It’s clear African Americans carried African religious practices with them throughout the U.S., as they redefined Christianity for themselves by incorporating parts of their own history and heritage.

“This is not the same Christianity that the master had,” says Cooper. “This is something where the former slaves are saying, ‘This is ours. This is different.’”

‘Silver linings were more vivid’

Cooper’s research includes stories about another family’s transformation, in a village known as Dink-town, in central Arkansas.

When she was a month old, Emma Ray and her mother, Jennie Boyd, were sold on the auction block in Springfield, Missouri. In her 1926 autobiography, Ray says her mother held her in her arms while the bidding took place. Two and a half years later, with the Civil War raging, Jennie Boyd’s owners, the Boyd brothers, fled south to Arkansas, fearful the encroaching Union soldiers would confiscate their enslaved people. Boyd, who was pregnant again, was already in labor when the brothers left with most of their enslaved people in tow.

For 80 miles, Boyd endured contractions until finally giving birth in a wilderness campground in Bethphage, Arkansas. Her own last name had been forced upon her by the Boyd brothers, but she made another choice for her new daughter, naming her Priscilla Bethpage, after her birthplace. Though Priscilla came into the world “sick and delicate,” Ray writes in her memoir, she lived.

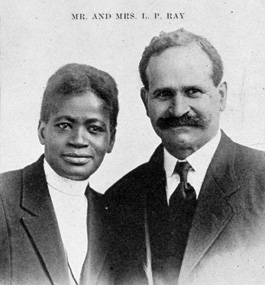

Courtesy Library of Congress

LOOKING BACK: Emma Ray and her husband, Lloyd, in a photo from “Twice Sold, Twice Ransomed,” her 1926 autobiography.

page 4 of 4

The traveling party pressed on, joined by a group of Confederate soldiers. They made Ray sing “Dixie” around the campfire at night. Several months after the group arrived in Arkansas, the Union Army swept in. Under their protection, Ray and Boyd returned to Springfield. They found shelter in a Northern sympathizer’s log cabin, staying there until the war ended in 1865. “When the glad tidings came that we were freed and the war was over, such rejoicing and weeping and shouting among the slaves was never heard before,” Ray recalled.

At this point, the family made a fateful decision. They went to live among other freedpeople who had left their owners en masse. They’d “dug holes in the ground,” Ray writes, “made dug-outs, brush houses, with a piece of board here and there, whenever they could find one.” In their first weeks of freedom, they had created Dink-town.

Ray’s father, John Smith, who had joined his family, leased an acre of land and built a small shanty for them. Smith had been a servant but never a household enslaved person, and had learned to read and write by stealthily observing the lessons given to his white employer’s children. The formerly enslaved people at the camp importuned him to write letters helping them find lost relatives. It was an almost impossible task, since they didn’t know the last names their family members were given after they were sold. “Mothers were hunting children, and husbands hunting wives,” Ray writes. “They kept my father very busy.”

Although donations kept them afloat, hardship prevailed. Sometimes Ray ate only a piece of cornbread until dinner. She walked through snow in shoes with soles attached by a loose string. One Christmas, the family didn’t have enough money to buy presents, so they wrapped wooden chips in paper and put them under a tree. This way, the children could be called up to retrieve a gift, even if they knew there was no point in opening it.

In 1868, Jennie Boyd died. She’d given birth to nine children, all of whom were now living in the family’s two-room dwelling. “Mother wanted to live to raise her children, as she had prayed so long for freedom, now it had come and she had to leave them,” Ray writes.

John Smith kept farming. The children grew older and found jobs. In fourth grade, Ray quit school to work as a servant and nursemaid. “The dark clouds of poverty were beginning to break a little,” she writes, “and silver linings were more vivid, and our intellectual skies began to shine more clear.”

Ray met her husband, Lloyd Ray, in 1881, moving with him to Kansas and then Seattle. She became a leader in the women’s Christian temperance movement, working with the destitute in jails, hospitals and local neighborhoods. Sometimes, she let recently released prisoners stay at her house for several weeks so they could find work and build up savings.

In May 1900, she left on a trip back to the community that had once been known as “Dink-town.” She was happy to report a remarkable change. “Instead of some of the old log cabins, there were cottages and beautiful yards,” she writes in her autobiography, “and I could see a wonderful improvement intellectually and financially, for which I was very thankful.”