Turning Points

Both Sides of the Truth

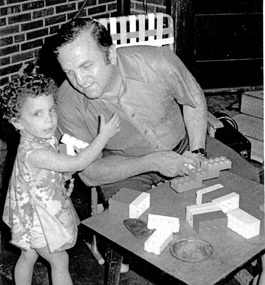

Courtesy Deborah Cohan

Deborah Cohan, around age 3, with her father

by Deborah J. Cohan, MA’02, PhD’05

For the past seven years, ever since my dad died, I mostly avert my glance as I walk past store displays of Father’s Day cards and gifts. But on occasion, I have been known to open one of the cards, testing myself. Would I send this to my father if he were still alive?

Sometimes I close the card and return it to its rack quickly, chastising myself for perusing something that no longer has a place in my life. It’s as though I have been caught shoplifting — my heart races, I’m scared and uneasy.

Other times, I caress the card; call up a memory of my dead dad; smile; and actually consider buying the card, writing a note inside, and sending it somewhere, anywhere, even to myself, so I can read it at a later time.

The truth is, my relationship with my father was not easy, perfect or pure, not by any means. He was adoring and affectionate. He was also abusive and difficult.

The same man who hid candy in his coat pockets for me to find when I was little; who rode amusement-park dodgem cars with me over and over again, despite an aching back that would leave him debilitated for days; who took me to practice skating so I could attend my best friend’s birthday party at a roller rink without feeling stupid and embarrassed; who left work to take me out for lunch when I was home from college; and who flew to Boston to find me an apartment while I finished up my master’s in Austin, Texas, before transferring to Brandeis to pursue my doctorate is also the same man who called my mother a “f-cking c-nt” at her 60th birthday party, who waved a knife at my face when I was 9 and who told me his life would be easier if I committed suicide.

The same man.

The girl who for decades wrote “For the best dad in the whole wide world” in cards, and who crawled onto her father’s lap to hug him and tell him she loved him became a woman who spent more than 10 years counseling abusive men in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to try to understand why people do awful things to people they love; who did a dissertation on the sociology of rage and how that emotion can be wielded destructively or rechanneled productively; who flew from Boston to Cleveland to surprise her dad for his 70th birthday; who helped him get settled in a new apartment after her mother asked for a divorce when he was 72; who baked him his favorite lemon cake for his 81st birthday, when he had dementia and was living in a nursing home; who kept all his medical information stored in her wallet, and drove around with his will and other files in the car, so she would never be caught off guard if something happened to him; and who fell sobbing to the floor at the Savannah, Georgia, airport when she got the news her dad had died, because she missed getting to Cleveland by six hours to see him one last time.

The same girl-woman.

And that man was once a boy who watched his father slug his mother and give her two black eyes, and sided with his mother and was angry at his father for hurting her, and still grew up to become that man.

This June marks my eighth Father’s Day without my dad. The Father’s Day cards will stare back at me. They’ll assault me. They’ll tempt me. They’ll yank me back to the times my dad and I had something to celebrate together.

Yet, the truth is, we still do. I have this life. The life he would have very much wanted for me. In South Carolina, a place he longed to move to and never did. Where the weather, for the better part of the year, is like spring and summer, his two favorite seasons. Where fuchsia- and violet-colored azalea bushes dot the stretch of highway between my house and where my partner, Mike, lives, two hours away. Where I found a way to interrupt and rewrite an intergenerational story of abuse.

Where I have come to see that the idea of “the best dad in the world” is both truth and fiction. And that the narrative of our lives is always blended.

Deborah J. Cohan, associate professor of sociology at the University of South Carolina Beaufort, is the author of “Welcome to Wherever We Are: A Memoir of Family, Caregiving and Redemption” (Rutgers University Press, 2020).