The Media Story of the Century

How the kidnapping and murder of the Lindbergh baby changed the rules of journalism.

PRYING EYES: Charles Lindbergh Jr., then 14 months old, in August 1931, with the family’s Scottish terrier and nursemaid Betty Gow.

by Jarret Bencks

In 1932, after the toddler son of pioneering aviator Charles Lindbergh was snatched from his crib at his parents’ Hopewell, New Jersey, home, the media coverage of the crime quickly became nothing less than a feeding frenzy.

This, says American studies professor Tom Doherty, is why the kidnapping and murder of the Lindbergh baby deserves yet more examination, nine decades later.

Doherty is a cultural historian with a special interest in Hollywood cinema and a keen sense of narrative. His latest book, “Little Lindy Is Kidnapped: How the Media Covered the Crime of the Century” (Columbia University Press, 2020), dissects the kidnapping through a unique lens: the media attention it garnered and the new era in news journalism it ushered in. As a writer for the Los Angeles Review of Books noted, “With scrupulous research and thrilling insight, [Doherty] reveals that the news coverage surrounding the kidnapping of Little Lindy is just as historically significant as the crime itself.”

“I’m a media person, and, like most of America in the age of Netflix, I have an obsession with true crime,” Doherty says. “The Lindbergh kidnapping case is right at that intersection — it’s a crime story and a media story.”

Five years before the kidnapping, Charles Lindbergh flew into the headlines as the first solo pilot to cross the Atlantic nonstop, a feat of bravura that won him public adoration and bottomless media attention. Two years later, he married Anne Morrow, daughter of the U.S. ambassador to Mexico. Their first child, Charles Jr. — dubbed “Little Lindy” by the press — was born in 1930, further fueling the media’s love affair with the Lindberghs.

What fascinates Doherty is how the three pillars of modern media — print journalism, radio and the newsreels (the early incarnation of what would become television and digital media) — coalesced as a result of the tragedy.

“Radio [had reached] a level of penetration where most Americans have one in their home,” says Doherty, “and that means they have access to real-time news broadcasting. That’s what they have ever after. Whether it’s broadcasting or digital, it is instantaneous information coming into your home.”

Newspapers were also thriving. New York alone had 12 daily newspapers in 1932; each sent out squadrons of reporters to cover the Lindbergh baby’s disappearance.

And, though they were still not subject to First Amendment protection, film newsreels were emerging as a medium to be reckoned with. Newsreel companies even persuaded the media-averse Lindbergh to share home-movie footage of the child, which was screened in New York theaters within 24 hours of the kidnapping as an all-points bulletin for moviegoers, the first time home movies had ever been incorporated into a newsreel.

The public’s emotional engagement with Charles Lindbergh meant the Lindbergh story was different from other notorious cases, like the O.J. Simpson murder trial or the Manson murders. “Our relationship to someone like O.J. is almost totally vicarious,” Doherty says, “He’s a celebrity whom we kind of know, but we’re not emotionally engaged with him.”

By contrast, all Americans knew who Charles Lindbergh was — and they loved him. His trans-Atlantic flight from New York to Paris was an extraordinary feat of personal courage during the depths of the Depression. “He had earned his fame, and he had not yet ruined his reputation with his antisemitism and isolationism that became apparent in the 1940s,” says Doherty. “People knew his wife, they knew the baby, and there was a deeper emotional connection to him on the part of virtually every American.”

This made the kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby “the kind of sensational story that outrages all of America,” Doherty says. “It really is the crime of the century.”

Adding to the suspense, the details of the story unfolded slowly, dramatically. Little Lindy was kidnapped in March 1932. A ransom payment was made in April. The baby’s body was found in May. The chief suspect, Bruno Richard Hauptmann, wasn’t arrested until September 1934.

Hauptmann’s murder trial began in January 1935 and ran for more than a month. “Every journalist, every novelist, anybody with any sort of journalistic ambition or back story is in Flemington, New Jersey, to cover this case,” says Doherty. “So you’ve got the best journalistic talent ever assembled covering it. The crime of the century gives way to the trial of the century.”

For the first time, forensic evidence played a major role during a trial. In the absence of fingerprints, a gun, a shootout, a dramatic confrontation or even the ability to place Hauptmann at the crime scene, forensics took center stage.

“And what you have is this relentless accumulation of forensic detail, which together leads unmistakably to Bruno Richard Hauptmann,” Doherty says. “Things like ransom money, bank records, handwriting analysis, analysis of the wood grain of a ladder. People are obsessed with these details. They are reading 3,000 words a day in The New York Times on the case.”

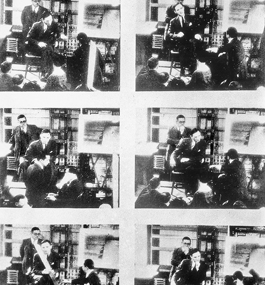

HAUPTMANN TESTIFIES: Frames from secretly recorded newsreel footage of the accused kidnapper’s cross-examination. He was convicted, and executed in 1936.

page 2 of 2

In an unexpected move, the trial’s presiding judge allowed the newsreels to record inside the courtroom during proceedings, though not when he was officiating from the bench or when witnesses were testifying on the stand. Yet when Hauptmann took the stand for his dramatic cross-examination by district attorney David T. Wilentz, news outlets surreptitiously recorded the confrontation. When the footage was released in newsreels, audiences were mesmerized.

A furious Wilentz demanded the newsreel companies withdraw the footage. Three of the companies complied, but two — Universal Newsreel and RKO-Pathé — defied the edict and suffered no consequences. As a result, motion-picture journalism gained some of the prerogatives of the First Amendment.

At the same time, the newsreel coverage of the case was seen as so sensational the American Bar Association in its code of ethics took the position that cameras should not be allowed in the courtroom. Decades later, state courts began to allow cameras back into the courtroom, though they are still banned in federal court.

The Lindbergh kidnapping left three significant legacies, Doherty notes. The first was a rich cultural and literary trove of material for writers and other artists to mine. Doherty points to two books as examples. One is Philip Roth’s novel “The Plot Against America,” in which Charles Lindbergh figures prominently. The other, surprisingly, is Maurice Sendak’s classic children’s book “Where the Wild Things Are.” “The little boy in the white suit, that’s the Lindbergh baby,” says Doherty. “As a young boy growing up, Sendak was terrified that something could happen to him, because if Charles Lindbergh’s son can be kidnapped, even a little boy in Brooklyn like him could be kidnapped.”

Second, the FBI’s reputation grew. Led by a young J. Edgar Hoover, the bureau provided forensic expertise in the Lindbergh case after the New Jersey State Police bungled evidence and showed general incompetence. The FBI investigated the case with far greater skill — and made sure its expertise was highlighted in the press. “It’s the beginning of a new standard,” says Doherty.

Third, Congress passed the 1932 Lindbergh Act, which made kidnapping a federal crime and, later, a capital offense.

The media’s coverage of the Lindbergh kidnapping and the public’s reaction to it was certainly fanned by “tawdry voyeurism” and reporters’ “competitive exhilaration,” Doherty writes in the preface to “Little Lindy Is Kidnapped.” But there was something finer at play, too: “It would be too cynical not to appreciate the sympathetic bond the story engendered on all sides — in investigators, journalists and ordinary Americans who grabbed a newspaper extra, reached for the dial or watched the newsreels in pity and horror. The news was taken to heart; it concerned the loss of a baby everyone knew by his nickname.”