A Political Brat Comes of Age

The scion of a progressive-politics family, Lily Adams ’09 has made her own way as a Democratic Party operative through smarts, moxie and, occasionally, sharp elbows.

Jörg Meyer

Lily Adams ’09

by Julia M. Klein

In 2016, Lily Adams ’09 was overseas on an exotic family vacation when she learned Kamala Harris, then a newly elected U.S. senator from California, wanted to interview her for the job of communications director.

“There’s not great cell reception in Zanzibar,” Adams recalls. “I had to find a place with Wi-Fi, and the only place was a really small bar. So I went there to do my interview.”

The improvisation worked, and Adams got the job. Her most persuasive calling card was her track record: She already had served as press secretary to two other Democratic freshman senators, Connecticut’s Richard Blumenthal and Virginia’s Tim Kaine.

“Starting a new office is challenging, obviously,” Adams says, especially when the senator comes in with a high profile, as Harris did. “But starting a new office during the middle of an unprecedented sort of new administration that was doing all sorts of outrageous things from day one is like building the plane as you fly it and getting shot at.”

The 34-year-old Adams — who in March left a senior communications post at the Democratic National Committee to join the U.S. Department of the Treasury as principal deputy secretary for public affairs — comes by her political acumen honestly. She is the granddaughter of former Texas Gov. Ann Richards, whose 1988 Democratic National Convention keynote address famously mocked George H.W. Bush as having been “born with a silver foot in his mouth.” Adams’ mother is Cecile Richards, former president of Planned Parenthood Federation of America and, more recently, co-founder of Supermajority, a women’s political-action group. Her father, Kirk Adams, is a longtime labor organizer who focuses on health care.

Harris was sufficiently impressed by Adams’ work with her in the Senate to ask her to oversee communications for her short-lived 2020 presidential bid. The campaign’s high-water mark may have been its seamless launch, for which Adams gives her then boss, now the U.S. vice president, “the lion’s share of the credit.”

“What was important to her in that launch,” Adams says, “was to try to touch as many communities, as many constituencies, as many platforms as we could. And she really did that flawlessly.”

Nevertheless, the press took notice of Adams. “[T]here’s always someone behind that kind of success, someone who helped plan and pull together the events, a strategist with a steely vision,” Texas Monthly declared in a profile of Adams.

Having worked with Adams on multiple campaigns, Mo Elleithee, founding executive director of Georgetown University’s Institute of Politics and Public Service, has become an admirer. “She knew how to have sharp elbows but not to go overboard,” he says. “A lot of communications professionals don’t seem to understand nuance. She got it.”

‘One nearly perfect granddaughter’

When her grandmother, then the Texas state treasurer, gave her celebrated DNC keynote in Atlanta, Adams had a featured role. Ann Richards praised the 1-year-old Lily, seated on her father’s lap in the convention hall, as her “one nearly perfect granddaughter” and pointed to her as a symbol of “the continuity of life that unites us, that binds generation to generation.”

Adams — named for actress Lily Tomlin after Cecile Richards saw Tomlin’s one-woman play “The Search for Signs of Intelligent Life in the Universe” — grew up immersed in electoral politics and labor organizing. As a baby, she accompanied her parents to picket lines, often in a backpack, as Richards recounts in her 2018 memoir, “Make Trouble.”

Courtesy Lily Adams

ACTIVIST DYNASTY: Cecile Richards, Ann Richards and baby Lily at the 1988 Democratic National Convention in Atlanta.

page 2 of 6

In the mid-1990s, the Adams home was the site of mass mailings and organizational meetings for the Texas Freedom Network, a progressive grassroots group started by Cecile Richards to combat the influence of the Christian Coalition. But Adams’ “most profound memories, and probably the most indelible,” she says, involve traveling with her grandmother during “the reelect,” Ann Richards’ losing 1994 gubernatorial bid. Along with a Cinco de Mayo celebration and homecoming parades, Adams recalls “being on countless stages at countless speeches.”

Off the campaign trail, Adams met Queen Elizabeth II twice, in Texas and at Buckingham Palace. “I had to take curtsy lessons to properly give her flowers,” she says. “There were just things that, looking back, were incredibly unusual.” In the moment, though, “it was just spending time with your grandparents.”

Both of Adams’ parents, who had roots in what she describes as “old-school labor organizing,” instilled a deep appreciation for working people in Lily and her younger siblings, twins Daniel and Hannah. Kirk Adams — the son of a milkman and a U.S. Postal Service employee — was the health-care chief at the Service Employees International Union, which represents people who work in health care, the public sector and property services. Cecile Richards organized for women’s rights and other progressive causes.

“I’ve witnessed two parents who got real self-worth and gratification from what they did for a living,” Adams says.

She attended public schools in Austin, Texas, and Washington, D.C. Her parents instilled in her a rigorous work ethic. “There was not a lot of appreciation for complaining in my household,” she says. “You weren’t allowed to feel self-pity, because there were a whole lot of people who had it a lot worse off than you.”

There was a family connection to Brandeis. During the 1997-98 academic year, Ann Richards served as the Fred and Rita Richman Distinguished Visiting Professor of Politics, and in 1998 she became a university trustee. Not surprisingly, she suggested her granddaughter check out the campus during her college hunt.

Adams’ visit to Waltham dovetailed with politics. In 2004, she attended the Democratic National Convention in Boston, at which John Kerry, U.S. senator from Massachusetts, was nominated for president and Barack Obama, an obscure Illinois state senator running for a U.S. Senate seat, delivered his famous keynote.

Brandeis alumni, she learned, included flamboyant anti-Vietnam War crusader and Chicago Seven defendant Abbie Hoffman ’59. Its faculty was home to Anita Hill, now a University Professor.

The university “felt like a place for people who wanted to pursue activism,” Adams says, “and so I thought, ‘This seems like the place for me.’ I applied early decision and got in. And that was that.”

‘She’s dyed-in-the-wool — this is her destiny’

At Brandeis, Adams majored in politics, rowed crew and spent the spring semester of her junior year in South Africa, “a totally exciting, life-changing experience,” she says, which immersed her in the country’s troubled racial history. She also worked part time for the SEIU, her father’s union, and volunteered on Deval Patrick’s 2006 Massachusetts gubernatorial campaign and then-Sen. Obama’s 2008 presidential run.

Adam Barish ’09, a filmmaker, photographer, writer and longtime friend, shares Adams’ passion for politics. But he says it never would have occurred to him to travel to New Hampshire to knock on doors for Obama. “It didn’t occur to her not to do it,” says Barish. The two of them headed north, slept at the home of another campaign volunteer and woke up at 4:30 a.m. to begin electioneering.

“She’s dyed-in-the-wool — this is her destiny,” Barish says. “There is not one part of me that is surprised by the world in which she finds herself or the level of success she has achieved. What made Lily special wasn’t that she had some kind of connection to anything. What made her special is that she was so focused and clear-eyed.”

Courtesy Lily Adams

CURTSY LESSONS: A beaming Gov. Ann Richards watches Adams present a bouquet to Queen Elizabeth II in Austin, Texas, in 1991.

page 3 of 6

Drew Elovitz ’09, global director of content strategy and senior managing editor at Clique Brands, roomed with Adams at Brandeis and bonded with her over a shared love of “Grey’s Anatomy,” “Sex and the City,” “Rent,” and the “Harry Potter” books and movies. Adams, a vegetarian, would cook rice and beans, and bake pies, “a big part of their family tradition,” Elovitz recalls.

Adams’ most powerful connection with a faculty member was with Eileen McNamara, a Pulitzer Prize-winning former Boston Globe reporter and columnist who is professor of the practice of journalism. At one point, news junkie Adams considered pursuing a career in journalism, completing a summer internship at ABC News’ “Nightline.” In McNamara’s classes, she says, she learned “to look at a set of facts, have a point of view and advocate for that point of view — which, frankly, is a lot of what I ended up doing.”

In a course on political packaging in America, coinciding with the 2008 presidential race, McNamara discussed Ann Richards’ memorable keynote. Adams waited until after class to alert her professor to the family tie.

McNamara had met Richards (who died of esophageal cancer in 2006) at a luncheon at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, on Boston’s Columbia Point. “She could have had a stand-up career as a comedian,” McNamara says. “No one ate because we were laughing too hard.”

By contrast, says McNamara, Adams is “more like her mother. She’s about the work and about the policies, the behind-the-scenes person getting it done. The student I saw in class is the political operative I see at work in the world. She’s not a showboater.”

“Lily is not gregarious the way that Ann Richards was,” Barish says. “Lily is a much more subtle presence. She’s still dynamite. I can’t tell you how much joy I’ve gotten over the years from just dry, dry banter with Lily Adams.”

Adrenaline rush

Over the December holidays, Adams discussed her career path during a video chat from the Long Island home of her future in-laws. She and Corey Ciorciari, a public policy consultant she met while working on Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign, live in Washington, D.C., and got engaged in mid-March. They have a wheaten terrier, Harper, named after novelist Harper Lee, author of “To Kill a Mockingbird.” (“It’s a boy,” Adams says, “but I figured no one cares.”)

Her graduation from Brandeis coincided with the last months of the Great Recession. “I didn’t start out with a five-year, 10-year, 20-year plan,” she says. “My only driving force at that time was to try to get a job, because the recession was so bad.”

Armed with a recommendation from McNamara, Adams secured an entry-level position as a press assistant on a Virginia gubernatorial race. The candidate was Creigh Deeds, then (and now) a Democratic state senator. “I was up at 4 o’clock in the morning, every morning, to compile all the news stories the rest of the staff needed to know about,” she says.

Adams met Elleithee, a political communications strategist she calls her mentor, on that campaign. “She was the kind of young go-getter who not only excelled at doing her daily task, but whom we realized we could assign more tasks to,” he says. “She was the person who a lot of times identified what I needed before I even knew I needed it.”

Elleithee says a month went by before he learned of her background, “which was funny because I knew her mom.” He and Cecile Richards had worked together in 2004 on America Votes, an umbrella organization for progressive causes.

Courtesy Lily Adams

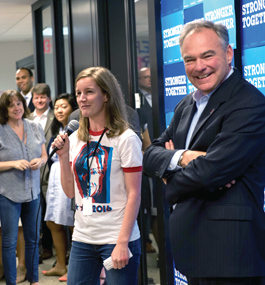

TOGETHER AGAIN: Adams introduces former boss Sen. Tim Kaine, who had just been announced as Hillary Clinton’s running mate, at the Clinton presidential campaign headquarters in Brooklyn in 2016.

page 4 of 6

Adams knew the Deeds race “was going to be a very uphill battle.” Republican Bob McDonnell ultimately crushed the Democrat by more than 17 percentage points. “I’m a competitive person, so I never enjoy losing,” Adams says.

Even so, she had found her calling. She says, “I felt at the end of that campaign that if I felt as fulfilled as I had and if I enjoyed it as much as I did — and we were losing by double digits — maybe this was something I wanted to keep doing. It was a job where if I worked harder, I did better.”

Knowing Adams was hooked on campaigns, Elleithee connected her to her next job, telling Ohio Gov. Ted Strickland’s communications director, “If you’re looking for help, this is somebody you can’t pass up.” Unlike her first race, this one was both close and high-profile. But 2010 was “a very, very challenging year for Democrats,” Adams says, and Strickland lost to former U.S. Rep. John Kasich by two points.

“Your career trajectory is at times held in the balance by millions of people whom you will never meet,” says Adams. “It’s a humbling line of work.”

Her next boss was Blumenthal, Connecticut’s newly elected senator. She worked as his traveling press aide, then his Washington-based press secretary, and gained another fan. Blumenthal calls her “a star,” citing her “tremendous intellect and insight, great judgment, and enormous maturity.”

But, for Adams, nothing could match the adrenaline rush of a hotly contested campaign. In 2012, Virginia Gov. Tim Kaine, whose civil rights record she admired, was running for the Senate against Republican George Allen, who had been both the state’s governor and a U.S. senator. Elleithee, a longtime friend and senior adviser to Kaine, brought Adams on as campaign press secretary. When the votes were tallied, Adams, for the first time in her professional career, found herself on the winning side. She followed Kaine to his Washington office.

“Lily is one of the most talented staffers I’ve ever worked with,” the senator says. “As good as she is in leading communications for others, I hope she’ll run for office in her own right someday soon.”

‘Is that Lily?’

Kaine is not alone in indulging in such speculation. Elleithee remembers an incident one day in 2014 at the Democratic National Committee, where he was communications director and Adams was his deputy. In the background, a television was tuned to MSNBC, which was airing a story about rising political stars in Texas. “Suddenly,” he says, “I hear someone yell out, ‘Wait a second. Is that Lily?’”

Sure enough, her face was on the screen, and a reporter was opining that, if she returned to her home state, she would make a strong candidate for governor. “She was teased mercilessly for this. And she was mortified by it,” Elleithee says. (“I was,” Adams confirms.)

“She’s not someone who seeks the spotlight,” Elleithee continues. “She just said, ‘All right, guys, can we just get back to work?’ There are a lot of people in this town who, if that had happened to them, they would have been sharing the clip far and wide.”

At the DNC, Elleithee says, Adams, already “a skilled spokesperson and a skilled communication strategist,” had “an opportunity to really grow her managerial skills.” So, when Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign came calling, she was ready. The campaign needed someone who could run communications in make-or-break Iowa, the site of the first caucus.

Elleithee didn’t have to recommend Adams. “She was already on their radar screen,” he says. “They wanted a real pro there.”

“It’s like the Super Bowl of politics,” Adams says of the Iowa caucus. “People descend from all over to try to cover it, to try to influence it, to volunteer. It was a great experience.”

Courtesy Lily Adams

MAKING HER CANDIDATE’S CASE: CNN’s Wolf Blitzer interviews Adams, then Kamala Harris’ communications director, before the Democratic presidential primary debate in Detroit in July 2019.

page 5 of 6

After Clinton edged out Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders in Iowa, Adams moved to the campaign’s Brooklyn headquarters, overseeing communications in the primary states. During the general election, her remit was communications in the battleground states, yet another high-profile post.

“It was always going to be a very close race,” she says about that campaign. “A million people have tons of opinions about what happened when and what went wrong.” But in late October, when then-FBI director Jim Comey reopened the investigation into Clinton’s handling of email as secretary of state, “that was when you could really feel the race tighten very significantly.”

On election night, Adams served as point person to argue close calls with television-network decision desks. She stayed at headquarters until after Clinton’s concession call to Donald Trump around 2:30 a.m. Cecile Richards’ memoir describes Adams returning to her parents’ Manhattan apartment to crawl into bed with her mother and weep.

“All of us were in shock at what this meant for the country,” Adams says. “It was a really scary moment.”

Making the most impact

The first few months of the Trump presidency were filled with new challenges. With Adams as her communications director, Kamala Harris garnered a reputation for effectiveness at Senate hearings, interrogating (among others) Attorney General Jeff Sessions; John Kelly, secretary of homeland security; Facebook co-founder Mark Zuckerberg; and, most famously, U.S. Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh.

“She really excelled at holding the Trump administration accountable,” Adams says. “She was committed to making sure that the way she asked the questions was understandable to people at home who did not live their lives speaking Capitol Hill jargon. When she asked Justice Kavanaugh, ‘Are there any laws that govern a man’s body?’ she’s not citing precedent. She’s just asking the plain question that is on everyone’s mind.”

Harris’ identity as a Black and South Asian woman guaranteed her heightened scrutiny as a freshman senator and, later, as a 2020 presidential candidate. For Adams, there was also an emotional tie. Harris’ warmth and adeptness at making personal connections reminded her of her grandmother, she says.

After Harris’ presidential campaign ended in December 2019, Elleithee again reached out to Adams. He recruited her as a fellow at the Georgetown Institute of Politics and Public Service, where, starting in February 2020, she ran a two-month student discussion group, “Tracking the Democratic Presidential Primary Race in Real Time.” Among the questions she covered: “What do you do when things don’t go according to plan or when a crisis hits your candidate?”

Following a short stint with a political action committee supporting Joe Biden’s candidacy, Adams returned to the DNC as senior spokesperson and adviser for the War Room, a rapid-response entity that countered Trump campaign messages. “There’s nobody on this earth, in this country, that Donald Trump won’t rip off,” she told MSNBC anchor Nicolle Wallace in September, displaying her sharp elbows.

Courtesy Lily Adams

CLEAR-EYED STRATEGIST: Consulting with Kamala Harris at the U.S. Senate in 2018.

page 6 of 6

In her new job at the Treasury Department, Adams will be helping to promote the Biden administration’s $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan and other efforts aimed at reducing income inequality in the U.S.

“It’s hard to remember a time when an incoming president faced so many challenges left for him by his predecessor on so many different fronts,” she says. “Trump has hobbled government at a point when government is needed more. It’s hard to turn that around on a dime.”

Asked where she sees herself in the future, she says, “The most honest answer is, I don’t know. If I’ve learned anything, it’s that life is long, and I’ll probably have many chapters to mine, I hope, God willing.”

The issues that particularly animate Adams include gender and racial equity, and access to health care. “I try to think through the lens of how issues impact working people, people like my dad’s parents,” she says.

Running for political office is “not something that I’m interested in right now,” Adams says, “but I also know that shutting the door on things arbitrarily is probably not a good idea either. My North Star will continue to be ‘Where can I make the most impact?’”

Elleithee, as ever, stands ready to help. If Adams runs for office, he says, “I have told her on more than one occasion I would be happy to serve as her press assistant.” Whatever she decides, he says, “she’ll be in the game. And she’ll be a real player.”

Julia M. Klein, a former political reporter for The Philadelphia Inquirer, has written for The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, Mother Jones and Slate. Follow her on Twitter (@JuliaMKlein).