A True Believer’s Long Fight

by Laura Gardner, P’12

Over the past three decades, Anita Hill has become arguably the most recognized — and influential — voice in the movement for better protections against gender-based violence. By nature private and scholarly, she was thrust into the spotlight at the U.S. Senate confirmation hearing for Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas in 1991. Her testimony that Thomas had sexually harassed her when she worked for him at the Department of Education and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission forever changed her life and career. Condemned by some, celebrated by many, she found herself at the center of a national conversation about sexual harassment.

In 1997, Hill left a tenured position as a law professor at the University of Oklahoma. Two years later, she found her intellectual and professional home at Brandeis, where today she is the University Professor of Social Policy; Law; and Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies, teaching at the Heller School for Social Policy and Management, and in the legal studies and African and African American studies departments.

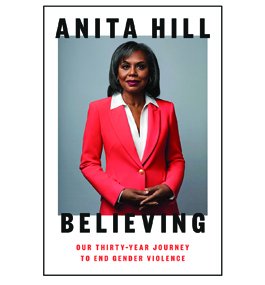

Last year, on the 30th anniversary of the Thomas hearings, Hill’s latest book, “Believing: Our 30-Year Journey to End Gender Violence” (Viking), was published. In it, she describes the breadth and depth of gender-based violence in schools and on college campuses; in the workplace; in the home; and at the highest levels of political, corporate and social institutions, and cites progress in recognizing and addressing the problem.

In January, she talked about the book — and the work still to be done.

How did you come to title the book “Believing”?

The title speaks to believing women and others who have been victims who come forward to tell their stories, and believing in their right to be heard. On a personal level, it’s about my 30-year journey and my believing that this work is my responsibility and opportunity to do, even in the face of setbacks and disappointments. I have never stopped believing in it.

When did you realize that fighting gender-based violence would become your life’s work?

There was no one moment. Initially, I thought I would study sexual harassment through case law, and that would shape my work. Then, in the later ’90s, I realized that looking at case law alone wasn’t enough, that there were social and political issues that had to be examined and understood. For instance, what was preventing victims from stepping forward with claims? That was one part of the evolution. The other part was how my role evolved. To be effective, if I were going to propose solutions other than litigation and discrimination complaints, I needed a broader understanding of the problem of gender-based violence.

The more I learned, the more I understood how much social and political factors shape everyone’s response to gender-based violence. I realized I was in a unique position, having experienced the problem, having been trained as a lawyer and a law professor. And now I benefit from learning and working with people who understand the issue through the lens of their disciplines.

Have we actually moved the needle on holding perpetrators to account, individually or institutionally?

People lack confidence in the system and trust in leadership. It is a really profound problem. It keeps people from coming forward. There is still a tendency not to hold powerful people accountable for bad behavior, and that’s a cultural issue, not just an organizational one.

There is a belief, one that is part of our culture, that people of high status in organizations are more likely to be truthful. And in many institutions, the failure to hold people of higher status accountable just comes down to finance. Those people are the most valued in the organizational structure; they are the ones making the most money, and the corporate investment in them is bigger. So status protects them from having to take responsibility for bad behavior.

We have made progress in identifying bad behavior and really understanding its harm. The terms “victim shaming” and “rape culture” are an indication that we understand the cultural and social pressure we put on victims to remain silent about the problems they face.

What about change in the legal system?

In cases of rape, at each step the number of victims participating in the criminal process shrinks. Even those who report to police and follow up by going to a hospital for a rape-kit examination are highly unlikely to see their alleged rapist tried. The end result is that seven in every 1,000 alleged rapes result in a felony conviction, according to U.S. Justice Department reports.

In civil proceedings, judges have held that repulsive behavior, such as groping and gender slurs in the workplace, are not violations of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. People have to put up with this kind of behavior despite laws against sexual harassment.

And we haven’t even begun to address bullying and hostile microaggressions in the workplace. Companies typically don’t define them as violations in their policies, even though the behaviors can and do contribute to toxic cultures in many workplaces.

There is much more to be done with the systems we have in place. There are plenty of places without real training programs or claims investigators, for example. And the training that does exist is largely compliance training — “check the box” — not aimed at eliminating the problems so much as protecting employers from lawsuits.

What’s the most important cultural change we can make now?

If we start addressing the problem in elementary school, we will be able to start to prevent it in high school, college, the workplace and at home. We need to start with young children.

In response to bad behavior, we need to stop sending cultural messages that it’s OK for “boys to be boys” and that girls must accept it. We need to stop telling girls that when a boy engages in disrespectful, sexualized behavior it’s a sign that the boy likes them.

The thing about progress is that it’s not linear. There can be sharp increases in protection. In the next 10 years, I believe we will see a good deal of progress.