Perspective

What’s Religion Got To Do With It?

A growing number of atheist and humanist chaplains are ministering to nonreligious young people on college campuses. But many Americans still question a nonbeliever’s moral compass.

Christina Reichl Photography / Getty Images

by Wendy Cadge and Penny Edgell

Several years ago, Chris Stedman, author of “Faitheist: How an Atheist Found Common Ground With the Religious,” visited Brandeis to speak to undergraduates who were taking a course on the sociology of religion. Stedman talked about being a born-again Christian, then coming out as queer, then becoming an atheist. He discussed how people of all religious and spiritual backgrounds — including those without a religious or spiritual affiliation — could work together to make the world a better place. Students, hungry to hear more, lined up after class to talk with him.

When he visited Brandeis, Stedman was one of a growing number of atheist and agnostic university chaplains. This number has continued to rise, largely because more and more young people describe themselves as unaffiliated with any religion. Nonreligious Americans have grown from 7% of the population in 1970 to more than 25% today. Fully 35% of millennials say they are not affiliated with any particular religion.

As sociologists of religion at Brandeis University and the University of Minnesota, we thought about Stedman’s message and its impact on students as we tried to make sense of the hoopla swirling around Greg Epstein, Harvard University’s atheist chaplain.

Last August, the more than 40 chaplains who work at Harvard unanimously elected Epstein — a humanist and atheist, the author of the bestseller “Good Without God: What a Billion Nonreligious People Do Believe” and a chaplain at Harvard since 2005 — as their community’s president. In this role, Epstein helps coordinate the activities of the chaplains, who represent a broad range of religious backgrounds.

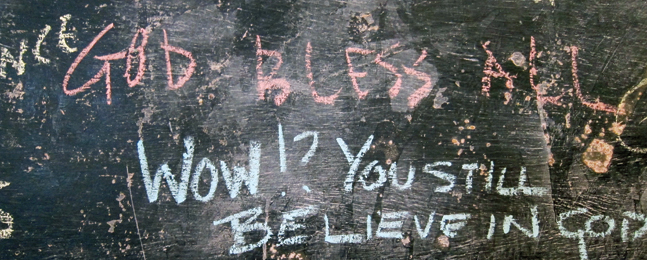

The election captured major media attention, with some outlets portraying the idea of an atheist chaplain as one more battle in the culture wars. It’s clear that even as Americans become more comfortable with alternative forms of spirituality, they retain a lingering moral unease about atheism. Epstein’s election and the controversy around it shows both sides of this tension.

From his position at the center of a larger cultural debate, Epstein talks often about his commitment to social justice and humanism, a philosophy that both rejects supernatural beliefs and seeks to promote the greater good. In doing so, he is becoming a spokesman for something new in America: an atheism that explicitly emphasizes its morality.

Although atheism has generated contention in the United States since Colonial times, the first widespread public expressions of skepticism toward religion date back to the late 19th century’s Golden Age of Free Thought, when lawyer and orator Robert Ingersoll lectured on agnosticism in sold-out halls across the country, drawing religious leaders’ ire.

In the 1920s, the so-called Scopes Monkey Trial put a spotlight on the teaching of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution in public schools, and underscored how struggles over religious authority affect American laws and institutions.

Ideas expressed by Black skeptics of religion, though often overlooked by scholars, influenced writer Zora Neale Hurston and, later, James Baldwin. In the 1960s, Madalyn Murray O’Hair successfully challenged mandated Christian prayer and Bible reading in the U.S. public schools, and founded the organization that became American Atheists.

More recently, a growing number of atheist and humanist organizations have promoted the separation of church and state, fought discrimination, supported pro-science policies and encouraged public figures to “come out” as atheist. Black atheists, not always feeling welcome in white-led organizations, have formed their own organizations, often centered on social justice.

Despite atheism’s increasing visibility, a large percentage of Americans do not trust atheists to be good neighbors and citizens. In a 2014 national survey, 42% of Americans said atheists did not share their “vision of American society,” and 44% did not want their child to marry an atheist. These percentages remained virtually unchanged in a 2019 follow-up.

At Harvard, in his role as chaplain, Epstein provides spiritual guidance and moral counsel to students, with a special focus on those who do not identify with a religious tradition. The 2019 survey reveals the challenges this population is facing: A third of atheists under 25 reported experiencing discrimination at school, and more than 40% said they sometimes hid their nonreligious identity for fear of stigma.

Humanism is increasingly accepted in the U.S. as a positive — and moral — belief system. A handful of America’s college campuses, including Yale, Columbia, Stanford and NYU, now have humanist chaplains. But atheism, perceived as a rejection of religion, remains more controversial in the United States, making an atheist chaplain a harder sell. Efforts to include atheist chaplains in the military, for example, have not succeeded.

Epstein openly challenges Americans’ persistent moral concerns about atheism, arguing that atheism is a morally anchoring identity for people around the world. He believes humanism can motivate concern for racial justice. And he has called for political leaders on the left to embrace nonreligious Americans as an important, values-motivated constituency.

His efforts mark a different approach from more militant high-profile atheists, particularly those in the Brights movement (who argue public policy should be based in science) and so-called New Atheist intellectuals such as Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens. Epstein does not position himself “against” religion; he seeks to cooperate with religious leaders on matters of common moral concern.

It’s too soon to say whether Epstein’s strategy of linking atheism to humanism, justice and morality will be successful in changing Americans’ attitudes toward atheists. It is, however, likely to keep him in the public eye as a symbol of the nation’s conflicting views on organized religion.

Wendy Cadge is a Barbara Mandel Professor of the Humanistic Social Sciences and the dean of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at Brandeis. Penny Edgell is a professor of sociology at the University of Minnesota. This essay is adapted from one first published on The Conversation website.