Revolution on the Nile

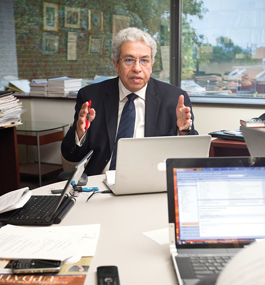

Photo by Tom Kates

Abdel Monem Said Aly is a senior research fellow at the Crown Center for Middle East Studies and president of Al-Ahram Center for Political and Strategic Studies in Cairo.

The Egyptian uprising belongs to a third generation of revolutions. This time, the collective demand for change is not for nationhood or citizenship, as it was in the American and French revolutions, the first wave of modern uprisings. Nor is the revolt in Egypt an expression of a radical social movement, as was the second generation of revolutions that swept Eastern and Central Europe in the latter half of the 20th century.

The Egyptian revolution was not fueled by violence or hierarchical political parties vying for power. This revolution is about peacefully sharing power and wealth among the masses and ending state despotism and corruption. It’s about ending the maltreatment of citizens in police stations; it’s about Egypt taking its rightful place in the world.

The galvanizing slogans of the American and French revolutions — life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness; liberty, equality, fraternity — of course informed the Egyptian uprising, but do not wholly define it. Egypt has added dignity to the revolutionary lexicon first inked centuries ago.

Instead of rejecting or destroying entrenched institutions in order to bring about real change, Egypt is harnessing them. Under the watchful eyes of the masses, three Egyptian state institutions — the national army (represented by the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces), the judiciary and the state bureaucracy — have been empowered to change the course of the nation in a direction that guarantees liberty, justice and dignity.