Perspective

Getting the Get

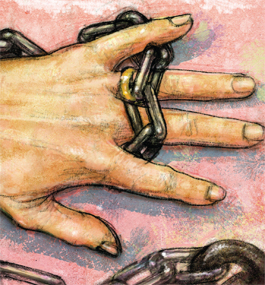

Lingering inequities in Jewish divorce law trigger a heightened interest in helping women break free from unhappy marriages.

Janet Hamlin

by Lisa Fishbayn Joffe

Last October, an FBI sting rounded up 10 people, including several Orthodox rabbis and scribes living in Brooklyn. They were members, authorities charged, of a “kidnap team,” hired to abduct a man and use not-so-gentle forms of persuasion, including cattle prods, to get him to agree to something.

That something was a Jewish divorce, known as a “get.” According to the FBI, the team had accepted tens of thousands of dollars from an agent posing as an Orthodox woman who desperately wanted a divorce. In situations like these, the unhappy wife is called an “agunah” (an anchored woman), chained to a dead marriage, perhaps to an abusive or absent husband, unable to go on with her life.

If this sounds like a plot twist from “The Sopranos,” it pretty much is. A similar scenario took place in episode three of the TV series. In that instance, however, Tony managed to prevail, and the fictional wife received her get.

The FBI arrests sparked widespread curiosity about the circumstances that could lead married women and apparently respectable rabbis to turn to crime to get a divorce. Most unhappily married Orthodox women don’t resort to gangster intervention. Nevertheless, they often pay dearly for their freedom. They may trade away their rights to family assets. Their parents may bribe the prospective ex-spouse with a “gift” of tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of dollars. Wives may even trade away the best interests of their children, agreeing to change custody arrangements made by a civil court.

When observant Jews in America marry, they do so under two legal regimes — the civil laws of the state and Jewish law. When they divorce in a state court, only the civil marriage is terminated. If they wish to be free to remarry under Jewish law, they must go to a Jewish court to dissolve the Jewish marriage. In America, the state never gets involved in enforcing Jewish law.

In Israel, there is no civil marriage, only religious law. All Jewish couples have to divorce in a Jewish court.

Today, the collision of archaic patriarchal laws with modern expectations for gender equality is roiling the divorce landscape in Jewish communities in America and around the world. Current research being conducted through the Project on Gender, Culture, Religion and the Law at the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute is exploring ways in which civil law might be able to bring egalitarian change to Jewish family law.

Over recent decades, American family law has become a system in which men and women have an equal right to ask for a divorce, share in assets accumulated over the course of a marriage and receive custody of children according to a civil court’s determination of the best interests of the child.

Jewish law has not experienced a similar transformation. Because husbands must agree to a divorce, they may use this power to coerce their wives into paying bribes or forgoing property or custody rights granted under civil law. Such unfair negotiations can leave women — and their children — impoverished after a divorce.

Just to be clear, contemporary interpretations of Jewish law do not condone the use of physical force to persuade a husband to release his wife. Even in Israel, the most coercive measure the state uses to enforce a rabbinical court order granting a divorce is to take away the husband’s passport or driver’s license. (In extreme cases, a husband can be imprisoned, though this power is rarely used.)

My research assesses the innovative — and violence-free — approaches that states, Jewish feminists and forward-thinking rabbinical authorities are promoting to address the agunah problem. Some attempts to define get refusal as a uniquely Jewish form of domestic violence are bearing fruit. Legislators in New York state, Canada, the United Kingdom and France have passed bills that allow civil courts to remedy get refusal by declining to grant the civil divorce unless a Jewish divorce has been delivered, or by threatening to give the wife a greater share of family assets to penalize a husband’s misconduct. The civil courts can also award women damages for intentional infliction of emotional harm or for breach of contract. In Canada, courts can go even further, by declining to hear from a spouse who refuses to remove the barriers to his wife’s remarriage.

Rabbis and rabbinical court judges — partly out of growing sympathy for women’s plight and partly to earn back credibility in the wake of their public failures to intervene effectively — have promoted prenuptial contracts to prevent get refusal. In response to a notorious case of get refusal in November 2013, the Rabbinical Council of America said it “strongly condemn[ed] the refusal of spouses to participate in the delivery and receipt of a get … when the marriage is functionally over and the relationship between the husband and wife has irreversibly ended.” The statement continued, “We deem the withholding of a get under such circumstances to be an exploitation of the halachic process and a manifestation of domestic abuse.”

Here at Brandeis, the Project on Gender, Culture, Religion and the Law has founded the Agunah Taskforce, which will provide information and advice to victims of divorce extortion, offer legal education to family lawyers in Massachusetts, and engage in research that pursues a comprehensive picture of the problem in the United States and seeks effective solutions.

No one likes the idea of gangster rabbis. They are clearly an anathema to Jewish law. Yet their existence highlights the pain and desperation of women trapped at the intersection of civil and religious law, and the importance of finding lawful solutions that can set them free.

Lisa Fishbayn Joffe, director of the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute Project on Gender, Culture, Religion and the Law, is an expert on clashes between civil and religious law.