The Dark Side of Justice

Sixteen years after a teenager was sentenced to life in prison, public-relations executive Scott Farmelant ’86 undertook an epic campaign to set him free.

Mike Lovett

Scott Farmelant '86

by Michael Blanding

It was a small moment of humanity in the midst of a rotten time.

Elmer and Inghild Raustein’s son Yngve, a 21-year-old aeronautics student at MIT, was killed — stabbed to death — by three teenagers in September 1992. Now, a year later, his parents had come from Norway for the trial of one of the teens, numbly sitting in a windowless courtroom in Cambridge, Mass., listening repeatedly to details of their son’s tragic last moments.

At one point during a break in the trial, as they walked through the courthouse, they ran into the parents of the defendant, Joe Donovan. He wasn’t the one who held the knife and stabbed their boy — that was a 15-year-old named Shon McHugh. But Donovan, who had just turned 17, started the fatal cascade of events by punching Raustein in the face. If not for that punch, the Rausteins’ boy might still be alive.

In the courthouse hallway, the Donovans, Mary and Joe Sr., stepped forward to tell the Rausteins they were sorry for their loss, sorry for their family. The Rausteins offered the Donovans a dignified thank-you and continued on their way.

The fleeting connection might have gone unnoticed had Scott Farmelant ’86, then a reporter for the Cambridge Chronicle, not been standing there. But Farmelant never forgot what he saw. “There was a decency there,” he says today. “These were decent people stuck in a horrible situation.”

Life in prison without parole. That’s the verdict that came down for Joe Donovan at the trial’s end. Given the circumstances of the crime, and the fact that Donovan wasn’t the actual killer, the harshness of the sentence surprised Farmelant.

He wrote a story about the sentencing. The years went by. His memories of the case faded. Then, in 2009, Farmelant received a package from Donovan’s family that convinced him he had to find a way to get Donovan out of jail.

The fight would be a lot harder than he knew.

The basic facts of Yngve Raustein’s murder were clear: On the night of Sept. 18, 1992, Donovan, McHugh and 18-year-old Alfredo Velez passed Raustein and fellow MIT student Arne Fredheim on Memorial Drive near the MIT campus. The two students were talking in Norwegian, and Donovan — thinking they were making fun of him — asked what they were saying. After a short argument, Donovan punched Raustein in the face. While Raustein was on the ground, McHugh pulled out a knife and stabbed him. One of the boys grabbed Raustein’s wallet as he lay dying, and all three fled.

News reports played up the town-gown angle of the murder — a promising MIT student viciously set upon by a gang of East Cambridge toughs. Bordering the MIT campus, the East Cambridge neighborhood was then a poor, working-class community of second- and third-generation immigrants of Irish, Italian and Portuguese descent. Loyalties ran fierce, and neighborhood teens learned not to step down from a fight.

Weeks before Donovan’s trial began in 1993, McHugh was convicted of first-degree murder. Tried as a juvenile, he received only 20 years in prison, with eligibility for parole after serving half his sentence. “Everyone knew it would be 15 years at the most, and the scuttle was 10,” says Farmelant. (McHugh eventually served 11 years.)

Velez and Donovan were not responsible for the killing, but they were charged with participating in a “joint venture” to commit armed robbery, a felony. The DA then exercised a seldom-used provision in the law that allows accomplices in a felony to be charged with “felony murder” for a killing that occurs in the commission of the crime, even if they did not participate in the murder itself.

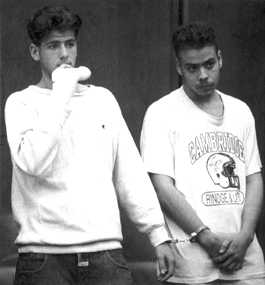

AP Photos

THE GUY WHO THREW THE PUNCH: Donovan (left) and Alfredo Velez at their arraignment, on Sept. 21, 1992.

page 2 of 5

In 1994, Velez would plead guilty to manslaughter in exchange for testifying against the other two boys, and receive 12 to 20 years in prison (he was out in eight). But Donovan refused to plead to second-degree murder, and the district attorney tried him as an adult. Velez testified Donovan had taken Raustein’s wallet. Donovan denied the accusation, saying his hand was so injured from the punch that he was doubled over in pain at the time. The first time he ever saw the knife, he said, was after the attack, as McHugh wiped off the blood.

Farmelant was filing a story at the Chronicle office on the Friday the jury convicted Donovan of armed robbery. What the jury didn’t know, however, was that, according to the felony-murder provision, the conviction also meant a guilty verdict for first-degree murder, carrying a mandatory sentence of life in prison without parole.

Smelling a story, Farmelant began calling jurors on Monday. He spoke to two women on condition of anonymity, both of whom began crying on the phone.

“They were heartbroken,” he says. “They were devastated about sending Joey Donovan away for life. The quote that stood out was ‘It was either find him guilty of armed robbery or send him home for milk and cookies.’”

He wrote a wrap-up story, decrying the discrepancy between the sentences of McHugh and Donovan. “The kid who did the killing was going to walk free, and the guy who threw the punch would never get out,” he says.

The case stayed with Farmelant even as he moved on to write for other publications — Philadelphia City Paper, The Improper Bostonian, Boston magazine, the Boston Herald. He got married; left journalism to take a job at a large Boston public-relations firm, where he specialized in crisis communications; and eventually started his own PR shop, Mills Public Relations. Over time, the Donovan story receded into the background.

Carol Hallisey calls herself Donovan’s “aunt,” even though her connection with the family comes through her long relationship with a cousin of his father. When she first visited Donovan at maximum-security MCI-Cedar Junction in 2008, she was so moved by the experience that she wrote him a note saying, “I will stand by you and do whatever I can, forever.”

Together with her partner, Al; Joe Sr.; and Donovan’s great-uncle Jack, Hallisey began pulling together news articles, and writing pages and pages of thoughts about the unfairness of the trial and its outcome. They mailed bundles of this material to everyone they could think of — lawyers, politicians and journalists. “We sent out hundreds of them,” Hallisey says. “We got very few responses.”

Farmelant received one of those packages. Sitting at an outside table at a bar in Boston’s Back Bay last summer, sipping on a Glenlivet with a beer back and carping about his constantly vibrating phone (“Man, would you stop sending me emails? This real-estate broker just sent me nine emails about his marketing brochure. You gotta love clients who are still banging out emails at 4:52 on a Friday”), Farmelant shakes his head as he remembers the package’s tone — too angry, too accusatory.

“It was how they felt, but it was never going to work,” he says. “The word they used was ‘railroaded.’ And, in my opinion, Joe wasn’t railroaded — that would mean the charges were trumped up. He just happened to be in a Kafkaesque situation no one could have ever imagined.”

Farmelant knew his crisis-PR training made him uniquely qualified to help this family. And he still remembered that moment all those years ago in the courthouse hall. “These were decent people, these Donovans,” he says. “And, boy, doesn’t that suck even worse.” When he picked up the phone at 10:30 one night to call Hallisey, he was committing to spending hours of his free time, which he didn’t have a lot of, on the Donovan case.

Hallisey was so excited to get Farmelant’s call she woke up Al. At a meeting with the family a few days later, however, Farmelant was blunt. “No one will care if you keep using this message,” he told Hallisey. “There is no recognition of who the real victim is here.”

He would help them, he said, but on one condition — he had to call the shots. “You’ve got to find something that works,” he said. “Public opinion is everything.”

The family agreed. On his way out the door, Farmelant tossed their package into the trash.

page 3 of 5

Shortly after that meeting, Farmelant went to Cedar Junction and spoke to Donovan through the thick glass. Donovan had been involved in several violent incidents after entering prison, and in 2000 was put in solitary confinement for four years for attacking a guard (he was later cleared in court, which found he acted in self-defense). In solitary, he began getting his head together, reading everything from Plato to Einstein. He hadn’t had another violent incident since being released from solitary in 2004.

When Farmelant met him, Donovan was hardly the image of a hardened criminal — soft-spoken and smart, he looked his visitor straight in the eye. He’d made a huge mistake, and he was sorry, he said. He told the story of the punch, the stabbing and the robbery exactly as he had at trial. It was a stupid thing to start the fight, he said, but he never imagined McHugh had a knife, or that the punch he threw would lead to Raustein’s death.

Donovan “was open and laid it all out,” says Farmelant. “He said he wouldn’t believe it if it hadn’t happened to him.”

Farmelant was impressed. “I walked out the door, and I was in,” he says. “Here’s a guy who has gone from being a dumb teenage kid to an adult among the worst of the worst. You name a bad murder case in Massachusetts — that’s somebody he’s eaten dinner with. And yet he had a decent, positive attitude, and his intelligence was evident.”

To Farmelant, this wasn’t a question of injustice, necessarily. Donovan was guilty of starting the fight that led to Raustein’s death, and he deserved to pay for his crime. But the punishment he’d been given was so far beyond what he deserved that some kind of corrective action was necessary.

As Donovan himself said in 2009, “McHugh murdered a kid, and they think he can be rehabilitated; and I am a year or two older and I didn’t kill anyone, but I can’t be? That makes no sense.”

Resigned to his sentence, Donovan held out little hope Farmelant would be able to help him, regardless of his intentions. “I personally thought it was BS,” Donovan said recently by email, “and he would lose interest once he realized how hard it was going to be. Boy, was I wrong!”

In fact, Donovan’s case became a passion for Farmelant. “It was the right thing to do,” Farmelant says. “No one else was going to step up for that kid if I didn’t. Somebody needed to get this sentence right, it was so wrong. I had the connections to put the family in touch with people who could help.”

He also had the PR insights. “If life is like a chess game, then sometimes I can see a couple of moves ahead,” Farmelant says. “I could see the moves the Donovans were going to make would lead to checkmate for them. I could also see that, if they made some different moves, they might turn this thing around.”

As a Brandeis undergrad, Farmelant had taken a class on the sociology of mental illness with Morrie Schwartz (later made famous by Mitch Albom’s book “Tuesdays with Morrie”) and a humanities class about religion and social justice taught by Reuven Kimelman. Both classes inspired his thinking on questions of justice and motivated him to become a journalist. As a reporter, he’d envied other reporters who spent years advocating for important issues. Now that he’d given up journalism, ironically, he had his chance.

He started by spending hours researching the law for grounds on which to challenge Donovan’s sentence. According to Massachusetts Criminal Procedure Rule 30, inmates could appeal a sentence if the law had changed or new facts emerged in their case. But that wouldn’t help Donovan. The facts hadn’t changed. They just didn’t fit the sentence, in Farmelant’s opinion.

The only course he saw was to get the governor to issue a commutation — an action similar to a pardon, only instead of forgiving the underlying offense, it merely reduces the length of punishment. Through a parent at his child’s day care, Farmelant recruited criminal-defense lawyer Ingrid Martin, who agreed to craft the petition.

There was just one problem. A Massachusetts governor had not approved a commutation in years.

I first heard about Joe Donovan in summer 2009 the way many people did — through a phone call from Farmelant. As a freelance writer who frequently covers criminal justice stories, I was immediately intrigued by the story. Meeting Donovan in prison, I was also impressed with his intelligence and poise. “I don’t even know what the hell I was thinking,” he told me, speaking so softly I could barely hear him. “I was just a dumb kid.”

As sympathetic as I found Donovan, however, the real story, Farmelant told me, was commutation itself. Although other states approved dozens of commutations a year, Massachusetts hadn’t approved one in more than a decade.

page 4 of 5

The reason was simple: Willie Horton. A murderer released on furlough in 1987, Horton had brutally raped a woman and tortured her husband. During the 1988 presidential election, Republican candidate George H.W. Bush used the crime to paint his Democratic rival, Massachusetts governor Michael Dukakis, as soft on crime.

In Massachusetts, the Horton case chilled the use of parole, pardons and commutations. It was simple, a number of political analysts and politicians — including Dukakis himself — told me: A governor had little to gain from letting an individual inmate out of prison, and everything to lose if that criminal went on to commit more crime.

Despite the Horton legacy, Farmelant and Martin saw an opening with new governor Deval Patrick, who had updated the guidelines for releasing prisoners, including in cases in which there was a “gross unfairness” in the “severity of the sentence” compared to “similarly situated defendants.” Donovan’s case seemed to fit perfectly. But the legal argument was only half the battle — if Donovan supporters were going to get Patrick to issue a commutation, they had to make it safe for him to do so, by winning the battle in the court of public opinion.

When my article “The Long Shadow of Willie Horton” appeared as a cover story in the Boston Globe Magazine, I never told my editor that Farmelant had come up with the title. The article was just one of many Farmelant pitched to journalists that year — using his PR skills to individually package each one. Other stories ran in the weekly alternative newspaper The Boston Phoenix, and on CBS News and New England Cable News. They all pushed the same message: Give Joe a second chance at a hearing.

In other words, Farmelant says, it was time to give second chances a second chance in Massachusetts.

During 2009 and 2010, Farmelant estimates he spent an average of four hours a week on the case, all pro bono, as he juggled an array of paying clients. He regularly consulted with Donovan family members, including Joe’s parents (who are divorced); several uncles and aunts; and Hallisey, who often served as the family’s go-between. Despite pressure from some family members who were understandably anxious for results, Farmelant urged patience as he followed a slow and steady strategy of building support.

An online petition calling for a review of Donovan’s case gathered several hundred signatures. At the same time, Farmelant solicited support from heavy hitters. His wife, Alison Mills, press secretary for U.S. Congressman Mike Capuano, helped put the story before her boss, who wrote a letter of support. Farmelant enlisted other politicians and lawyers, including Harvard law professors Charles Ogletree and Alan Dershowitz. He even got a letter of support from the judge in Donovan’s case, Robert Barton, who said he believed Donovan had served his time.

But none of those supporters was as important as the ones Farmelant was determined to get. “From the beginning, I said this goes nowhere without the Rausteins,” he says. He found Yngve’s brother Dan-Jarle, a heavy-metal musician and arm-wrestling champion, online and arranged a conversation with the Raustein parents. “They made it very clear that Joe Donovan had caused them irreparable damage, for which he would never be forgiven,” says Farmelant. “But this wasn’t an issue of forgiveness; it was an issue of justice. And they found the punishment way too harsh.”

With letters of support from the Rausteins and others, the Donovan team was ready to go with the commutation petition in early 2010, an election year. They decided to submit it to the parole board in June, hoping to get a hearing in September, and a favorable recommendation to the governor by November. At that point, Farmelant reasoned, the governor would either be re-elected with political capital to burn, or on his way out the door with nothing to lose.

“We felt it was a slam-dunk to get a hearing,” he says. Unfortunately, the parole board felt differently, denying a hearing and giving the petition an “unfavorable” recommendation that August. The governor could still overrule the board, but now the timing was terrible — right in the middle of the election. “We messed up,” says Farmelant. “We were too soon.” Still, he held his breath, hoping that a re-elected Patrick might approve a commutation soon after Jan. 1.

Two days after Christmas, Farmelant opened the newspaper to find a front-page story about a paroled criminal who had robbed a sporting goods store, then shot and killed a police officer. Farmelant’s heart sank. He knew exactly what this meant for Donovan. The official denial by the governor was just a formality.

After pinning their hopes on commutation and seeing it fail, the Donovan family was dispirited. “Every time we would become hopeful and get rejected was terribly upsetting,” says Hallisey.

Farmelant was depressed, too, but didn’t allow himself to wallow for long. “It was a bummer, man,” he says, “but we wake up the next morning and away we go.”

That’s typical for him, says his wife, Alison: “Scott is very tenacious. He is also a very positive person. He never loses sight of the outcome he wants to achieve.”

Even as the commutation petition was being considered, several cases that had the power to change everything for Donovan were wending their way to the U.S. Supreme Court. In May 2010, the court ruled in Graham v. Florida that, due to the latest science showing that teenagers’ brains aren’t fully developed, juveniles could not be sentenced to life without parole for nonmurder crimes.

AP Photos

BEFORE THE BOARD: Donovan listens as Carol Hallisey speaks at his May 2014 parole hearing.

page 5 of 5

Another case on the court’s docket, Miller v. Alabama, had the potential to do the same for cases involving murder. Farmelant and the team spent a hard year waiting for the court’s ruling. “We couldn’t do media because we didn’t have a story to tell,” he says. Still, he made regular check-in calls to politicians and journalists, constantly trying to keep the Donovan case in the forefront of their minds. Finally, in June 2012, the Supreme Court ruled that while courts could impose life without parole in juvenile murder cases, they couldn’t do it automatically — paving the way for Donovan to at least get his long-awaited hearing.

In January 2014, Massachusetts decided the parole board would hold sentencing hearings for 65 inmates who had been sentenced as juveniles — with Donovan as the first case.

All of Farmelant’s groundwork paid off when, on the eve of Donovan’s sentencing hearing, The Boston Globe published an editorial suggesting he go free.

On May 29, 2014, Donovan, now 38 years old, stood before the parole board in a black button-down shirt and apologized again for his part in Raustein’s murder. “I was such a stupid kid,” he told the six assembled board members, who asked him pointed questions about the violent incidents during his first seven years in prison.

He took responsibility for his behavior, assuring them that the time spent in solitary reading science and philosophy books had changed him. After one board member, seeing Einstein’s book on the theory of relativity on his reading list, quipped, “Haven’t you been punished enough?” Donovan perked up. “I’m a big Einstein fan — the guy’s a genius!” he said.

Hallisey felt a sense of unreality watching Donovan stand before the parole board after all the years of trying to get someone — anyone — to pay attention. Even so, the impassive faces of the parole board members left her with a sinking feeling. “I didn’t feel any hope at all when I left there that day,” she says.

Farmelant felt differently. Before the hearing, he told Donovan, “You have one mission — to make them believe that if they let you out they aren’t going to see you again.” Everything he saw in the room made him feel Donovan had succeeded. He was contrite, nondefensive, even funny at times.

“I kept coming back to one point — they had no reason to say no,” Farmelant says. But even he began to lose resolve as a month, then two, went by without word, while other inmates were freed.

Finally, on Aug. 7, he was in a parking garage elevator when a reporter phoned him with the news. Farmelant hugged the colleague he was with, shouting, “Joe Donovan just got paroled!” He immediately placed a call to Hallisey, who started sobbing. The parole board, he told her, had voted 6-0 to free Donovan.

The board required that Donovan spend six months in a medium-security rehabilitation program and a year in minimum security before his release. If all goes well, he will be out of prison in early 2016.

Hallisey gives Farmelant credit for Donovan’s release. “Scott was an angel sent from heaven,” she says. “He broke open the doors to a broken legal system.”

Farmelant brushes away the compliment, but is clearly pleased with the part he played. “There was never any doubt in my mind that Joe was going to be freed someday,” he says. “Now there is no doubt in my mind that the criminal justice system is never going to see him again.”

In the end, Donovan believes, the public attention tipped the parole board in his favor. “If Scott didn’t help to put them in a tough position, it would have been unlikely they would have granted me a favorable decision,” he writes in an email. “He will forever have my gratitude, admiration and friendship.”

Twenty-two years after losing his freedom, Donovan has gotten his second chance. The rest is up to him.

Michael Blanding is an award-winning magazine writer and a senior fellow at Brandeis’ Schuster Institute for Investigative Journalism.