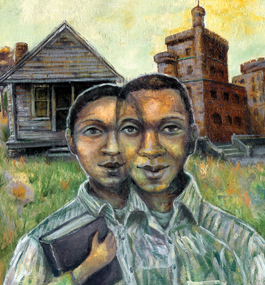

Turning Points

Freedom Lessons

Tonya Engel

by Roy DeBerry '70, MA'78, PhD'79

In 1956, when I was 9, my family moved from rural Marshall County to Holly Springs, Miss., so I could attend the Rosenwald School, a larger “consolidated” institution.

Unlike my old school, my new school had running water, electricity and more than one teacher.

Like my old school, it was segregated.

The consolidated school had come to Holly Springs after the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision. The local school district managed to avoid integration by building a brand-new school for the “colored” children, albeit one outfitted with secondhand books, and inferior lab space and equipment.

At 9, I knew a lot about the complexities of race relations. My parents and grandparents had taught me to practice the golden rule in my dealings with others, to be tolerant and accepting of everyone, even in a rigidly segregated and racist society.

Despite their patient instruction, I failed an early test at age 6 when I answered a knock at my grandmother’s front door. A middle-aged white man dressed in ragged clothes stood on the doorstep. I walked back to my grandmother. “Who was there?” she asked.

“An old white cracker,” I said.

My grandmother went to the door, invited the man into her kitchen, gave him some food and water, and allowed him to be on his way. “Don’t you ever call a human being a ‘white cracker’ again,” she told me, the disappointment audible in her voice. “That man was hungry and needed some food.”

The year before my family moved to Holly Springs, Emmett Till, a 14-year-old black boy from Chicago, was killed in a small Mississippi Delta town. He was murdered because of some alleged social interaction with a white woman in a grocery store — it’s possible that he whistled at her. A few nights after the encounter, the woman’s husband and an accomplice abducted Till, beat him brutally and shot him in the head. The boy’s remains were found three days later in a river, weighted down by a

cotton-gin fan tied to his neck with barbed wire. With Till’s mother’s permission, Jet magazine printed a photograph of his mutilated body lying in a coffin.

Fear and dread descended on my friends and me. Our parents and other black adults had taught us the code of survival — what to say and what not to say to whites. Still, when I heard what happened to Emmett Till, I knew that could easily happen to me, too.

In 1964, while I was still a student at Rosenwald, a Freedom School came to Holly Springs. An offshoot of the Freedom Summer — the campaign that brought activists to the South to register voters and work for social justice — Freedom Schools offered instruction in topics the segregated schools wouldn’t touch: political activism; constitutional rights; the work of Booker T. Washington and Langston Hughes. The classes met in public spaces — or even under a tree — staffed by volunteer teachers, community organizers or faith-based folks, people who were black and white, young and old.

Hungry for excitement, I drifted down to our Freedom School, and was elated to find myself in the midst of a dynamic, relevant movement. I met Bob Moses and Stokely Carmichael, and so many other young SNCC, CORE, NAACP and SCLC freedom fighters who became household names.

As part of my Freedom School responsibilities, I stood on doorsteps, trying to persuade black voters to go to the polls in spite of their fears of economic reprisal, intimidation or physical violence. I also served as a guide for the Freedom School teachers and volunteers who came to Holly Springs. I taught them vital local information, including where the back roads were. Back roads helped me evade the Ku Klux Klan, and probable torture and death, more than once.

Ever since Emmett Till’s murder, I’d known that segregation was wrong and had to be abolished. Now I knew that this was the time. I was an active participant in my own liberation and the liberation of others.

Soon, everything I was doing, everyone I was meeting would catapult me 1,300 miles to the northeast. In 1966, a decade after moving to Holly Springs, I enrolled at Brandeis.

I had learned so much. I was ready to learn much more.

Roy DeBerry is co-founder and executive director of the Hill Country Project, an oral-history effort that collects stories from Mississippi residents who lived through the civil rights struggle. He is a former vice president at Jackson State University.