Nerd Life

By founding the thriving MakerLab at Brandeis, Ian Roy ’05 hit the reboot button on himself.

Mike Lovett

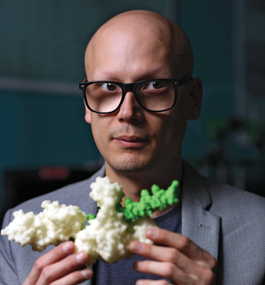

BRAINSTORM: Ian Roy ’05 (top), flanked by Hazal Uzunkaya ’14 and Tim Hebert, with several MakerLab denizens.

by Laura Gardner, P’12

The first thing you notice about Ian Roy ’05 is that he has no hair on his head. No eyelashes or eyebrows either.

He doesn’t mind if you ask why. Alopecia, an autoimmune disorder that attacks hair follicles, made his hair fall out in the space of a month when he was a senior at Brandeis. “It caused huge body-image issues,” he says in his trademark million-words-a-minute style. “I love it now, but at the time it was really hard.”

Difficult losses — and there have been significant ones, way beyond the loss of his hair — are actually a source of creative energy for this level-headed, self-possessed 34-year-old. They inspired him to “reboot his life,” he says, like he did when he created the MakerLab at Brandeis four years ago. One of the first makerspaces at a liberal-arts school, the MakerLab occupies a corner room in the Farber Library. It’s packed with 3-D printers, virtual reality (VR) gear, 3-D scanners, little robots, soldering tools and other kinds of instruments used in rapid prototyping and small-scale manufacturing.

The MakerLab’s ethos is explained on its website: “We are pragmatic dreamers; innovators with an outside-the-box question-everything mentality, with extreme respect for human rights and equal access, passionate about enabling all humans.”

“Anybody can make something — that’s our stance,” says Roy. “I can’t paint or sculpt by hand, but if you give me a machine, I can make anything.”

The MakerLab isn’t on the same physical scale as makerspaces at big engineering and research schools like MIT and Stanford. But you don’t have to be an engineer or even a techie to join the Brandeis maker community, and access isn’t limited by department or curriculum. The MakerLab makes emerging technology and an innovation mindset accessible to everyone on campus.

“We are democratizing technology,” Roy says.

Tech to the rescue

Roy estimates that the MakerLab — which he launched alongside Tim Hebert, now an embedded systems and robotics specialist in Library Services, and Hazal Uzunkaya ’14, a research technology specialist — interacts with one out of five students on campus.

When you visit the MakerLab, you see clusters of students immersed in personal or academic projects, even business startups. One train buff is designing and printing an electronic train set, complete with switchable tracks. Students in the 3-D Prosthetics Club have designed and printed two prosthetic hands for children born with incomplete limbs. Other students print 3-D molecules to visualize molecular structure and function.

Gabe Seltzer ’18, a computer science major and education minor, is a typical denizen of the MakerLab, which is open whenever the library is open. When Seltzer was a first-year, he thought the MakerLab was “a crazy sci-fi world,” he says. Before long, he was president of the 3-D Printing Club. Then, for two summers, he interned at E3D Online and Simplify3D, two of the biggest players in 3-D printing hardware and software innovation. Although he turned down an offer to work full time at E3D Online before graduating, he still freelances there.

“The MakerLab pretty much changed the trajectory of my life,” says Seltzer. “I never thought that would happen.”

Daniela Dimitrova ’16, an IBM software engineer, joined the MakerLab as an art history major. After learning how to create VR environments, Dimitrova spearheaded a VR exhibition for the Rose Art Museum that re-created its historic 1967 Louise Nevelson show. When that experience jump-started her interest in technology, she added a computer-science minor to her studies.

Mike Lovett

Ian Roy

page 2 of 3

Remade in the crucible

Few people understand the culture at Brandeis better than Roy. During his student years, he majored in economics and philosophy, minored in film studies, managed the library’s Help Desk and captained the ski team.

“It was a 100 percent commitment to those five things,” he says. “I did nothing else.”

Life changed after graduation. Roy moved to Los Angeles, struggled to become a film screenwriter and spiraled into mental illness. He saw a psychologist for the first time in 2005. At his lowest point, Roy says, he was taking more than a dozen prescription pills daily to help him manage anxiety disorders. His weight seesawed, from more than 225 pounds to less than 100.

Roy’s anxiety developed into panic attacks, including vomiting episodes that landed him in the hospital for weeks. In 2009 and 2010, he says, he spent nearly half of each month in ICUs or psych wards suffering from extreme suicidal ideation. Meanwhile, he “failed miserably” at writing screenplays, he says.

Yet Roy’s life in LA wasn’t entirely bleak. He worked at a high-end jewelry wholesaler from 2005-10, photographing jewelry and providing tech support. That’s where he encountered his first 3-D printer. He spent several years learning about the emerging field of 3-D printing fabrication, honing his photography and tech skills along the way.

In late 2010, Roy admitted defeat as a screenwriter and returned to his hometown, Acton, Massachusetts. He was home for less than two weeks when the unthinkable happened: His mother took her own life in the family home. “No one saw it coming at all,” he says. “It was completely out of the blue.”

That was when, Roy says, he “stared right into the abyss.” The tragedy was compounded by the fact that many in his family blamed him for her death and severed ties. “There were a couple of years where I would call every number in my phone, and no one would answer.”

But the worst year of his life sparked a turning point. “I had lost myself, and my mother’s death helped me find Ian again,” Roy says. “In retrospect, I am sure that after the years of trying to prevent me from taking my own life, this was the only way she could see to save me.”

Facing rock bottom, he contemplated the words of the ancient Jewish philosopher Hillel: “If I am not for myself, who is for me? If I am not for others, what am I for? If not now, when?”

For Roy, whose self-proclaimed brand is “nerd life,” working in tech was the obvious solution. “I knew how to think in that space,” he says. “And I wanted to contribute to something.”

Exciting — and practical

Rebuilding his life wasn’t easy. In 2012, Roy applied for four different positions in the Brandeis library over nine months before getting hired in the hardware repair shop. “I wanted the job so badly when I saw the shop. I said I would work for free,” he says.

Anne Livermore, then the library’s associate director for desktop computing, had known Roy casually when he was the undergraduate Help Desk manager. “When I interviewed him for the job in the repair shop, I was struck by how interested in the world he was,” she says. “And, as much as I suspected he would surprise me, I couldn’t have anticipated how much. I knew he was smart. I did not know he was brilliant.”

Mike Lovett

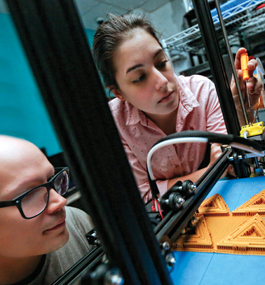

FABRICATING: Roy and Uzunkaya calibrate the extruder gear of a 3-D printer.

page 3 of 3

Roy fixed Apple and Dell computers in the repair shop. He tapered off his meds completely. He started doing instrument machine support in campus research labs, whose arcane hardware and software problems were beyond the Help Desk’s capacity to solve. With Hebert and Uzunkaya, he founded a research technology and innovation group to explore emerging technologies.

For two years, Roy says, he and his colleagues evangelized the concept of an open-access makerspace in the library. “Everybody wanted to do something with 3-D printing and VR,” he says. “I kept asking, ‘What is exciting, and what is practical?’ I wanted people to realize we could integrate these technologies across campus.”

In 2013, Roy went to a BITMAP (Brandeis Initiative for Tech, Machines, Apps and Programming) student club meeting to pitch his idea for a makerspace, and was urged to meet first-year Noah Fram-Schwartz, who had a 3-D printer in his dorm room and was interested in launching a 3-D Printing Club. He did, and Roy started advising it.

Before Fram-Schwartz went to work full time at Google at the end of the year, he had taught Roy the fine points of fused deposition modeling desktop 3-D printing, as well as how to negotiate with equipment vendors, and attract sponsorships and funding.

The MakerLab opened in 2014 with a dedicated space in the library. “Ian’s job was figuring out the conceptual direction,” says Livermore. “My job was to support him and get the hell out of his way.”

When the first batch of library-owned 3-D printers arrived, Roy, Uzunkaya and a student worker spent an entire Sunday setting up the hardware. After becoming familiar with the machines, they learned computer-aided design tools to draw in 3-D and scanning techniques to bring real-world objects into their designs.

From the beginning, the MakerLab has been heavily fabrication-based. VR, which came later, is being developed. And as the Brandeis maker community grows in multiple directions, it’s drawing more and more students and faculty into its orbit.

Last fall, Roy taught his first course, on digital fabrication with robotics, at Brandeis International Business School. Eight IBS students successfully built 3-D printers from scratch.

Along with Hebert and Uzunkaya, Roy consults with several schools, including Wellesley and Colgate, to help them build their own maker communities. Maker Faires, printathons and 24-hour hackathons are part of the mix, with student involvement at every level.

In yet another leading-edge pursuit, Roy has become a Federal Aviation Administration-certified drone pilot. He’s built more than 50 custom drones, and is teaching others how to become certified drone pilots for their own course work or research.

“Our work is all about expanding what is possible,” Roy says. “Tech is just a medium. This work is my dharma, and my goal is to expand the landscape of possibility for all humans.”