Mississippi Smoldering

When a handful of undergraduates dig into one state’s segregated past, they question themselves as much as the harsh truths they unearth.

by DAVID CUNNINGHAM

Even within the Jim Crow South, Mississippi was known for its ruthlessness in enforcing segregationist practices that ensured African-Americans attended substandard schools, lived in shoddy housing, received the poorest health care and were denied the most desirable jobs. Even as the civil rights movement of the 1960s brought momentous change to the state, the Ku Klux Klan flourished and the police more often harassed than protected blacks, who were prevented from gathering in the same public places as whites.

In the long shadow of this history, 11 Brandeis students of mine last summer became amateur gumshoes, unearthing dog-eared community directories and moldering arrest logs, court dockets and school board minute books. Their efforts contributed to a research project aimed at more fully uncovering the legacy of racial segregation and the state’s civil rights struggles.

Throughout June and July, Brandeis students worked with their peers from Jackson State University to locate and reproduce more than 17,000 pages of documents from state and local government offices and conduct nearly three dozen interviews with local officials and residents. Along with teaching assistants Ashley Rondini, Ph.D.’10, and Elena Wilson, M.A.’11, and me, and guided by the knowledge and experience of our many local partners, these students gathered in classrooms, attended community events, and met with civil rights leaders and influential officials. We spent hours in vans traversing highways and back roads in sweltering Mississippi heat. We ate, laughed and cried together.

The Meredith Mississippi March was named for James Meredith, who in 1962 became the first black student to attend the University of Mississippi. In 1966, Meredith, then a law student, led the march from Memphis, Tenn., to Jackson, Miss., to encourage African-Americans to register to vote.

page 2 of 5

The students’ original research was the core of “Civil Rights and Racial Justice in Mississippi,” a new offering of the Justice Brandeis Semester program. (Watch a related video at www.brandeis.edu/magazine.) The JBS provides students the opportunity to work with a small group in an immersive academic experience that integrates classroom work with community involvement.

But the work was far more than an academic exercise. In partnership with the Margaret Walker Center at Jackson State and the University of Mississippi’s William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation, the program’s research supported the Mississippi Truth Project, a grass-roots social-justice initiative that seeks to integrate oral history and documentary evidence to connect past discrimination and present-day racial inequity.

|

|

Sidebar Video |

|

Following in the footsteps of truth commissions in South Africa and more than two dozen other nations around the globe, the Truth Project aims to, in the words of its organizers, “allow the state to constructively engage the confusion, division and bitter feelings” that remain from the state’s segregated past to “shape an inclusive and equitable future.”

Our group set up camp in Mississippi’s capital, Jackson, and three other communities around the state: Natchez, a bastion of antebellum culture perched high on the bluffs of the Mississippi River in the state’s southwestern corner; McComb, a gritty railroad city midway between Jackson and New Orleans; and Philadelphia, the small town infamous for its officials’ collusion with the KKK in the 1964 killing of civil rights workers Andrew Goodman, James Earl Chaney and Michael Schwerner.

The student dispatches that follow offer a glimpse into a singular Mississippi summer.

page 3 of 5

|

|

Jake Weiner ’13 |

FORGIVE AND UNDERSTAND?

By Jake Weiner ’13

To me, guilt is one of those funny emotions that can strike the hearts of wrongdoers at seemingly right or random times, but forgiveness is much harder to muster. Families who forgive and understand the criminals who have wronged them are justly considered strong. Yet in the instances of civil rights era cases, I would personally be less willing to accept the grievous shortcomings of those who have done wrong, less willing to forgive them their crimes.

Call it my bias, but I believe that crimes of prejudice and hatred are on a different level from petty crimes, or even murder committed in a moment of passion. At my Quaker high school, we were taught that everyone was equal and had “that of God,” so all criminals and their families should be held alongside victims “in the light,” or in a special place within our prayers. I’m pretty sure I learned similar sentiments at Hebrew school: Understanding evil is a way of humanizing the people who perform it.

At the same time, it’s a good thing Jews do not explicitly believe in hell and Quakers do not talk about it, because if I had the opportunity to sit down with a Nazi who was personally responsible for perpetrating crimes of hate against my family, I might dispense with forgiveness and understanding, hoping instead that there was a special place for him after death — preferably somewhere warm and fiery. Look at Klansman Edgar Ray Killen. Even though he was convicted on three counts of manslaughter, he remains an unrepentant racist. Regardless of whether he asks for it, should he be forgiven? Should any effort be made to understand him?

|

|

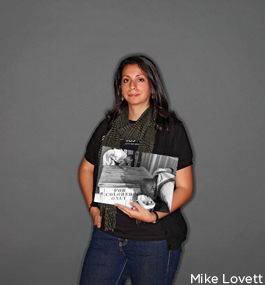

Gabi Sanchez-Stern ’12 |

IT’S NOT BLACK AND WHITE

By Gabi Sanchez-Stern ’12

During this first week I’ve been struggling to understand my impressions of race relations in Mississippi today. I tried to come here with an open mind but have quickly discovered I had preconceived notions about what I would see and what it would be like. Most of the time it’s been fun to be surprised by the unexpected. For example, I never thought I would see hippies in Mississippi, but on our first night out in Jackson we stopped at a café full of young people with tattoos and dreadlocks! I had to remind myself that I was in Jackson, Miss. It made me think, “Oh, things are actually more like home than I thought. This place isn’t so different from any urban center in the North.”

Other times, however, I feel like things might not have changed much over the decades and the same racial tension of half a century ago still exists buried below the surface. The first time I felt this way was when we went to a minor league baseball game in Jackson. For the first time in my life I was aware of the race of the people around me, and I noticed it was a mostly white crowd, in stark contrast to the 99 percent black campus of Jackson State, where we are staying. Is this a sign that, 50 years after the height of the civil rights movement, race relations in Jackson remain almost the same? Or am I reading too much into this situation? I wonder if the de facto segregation I am seeing in Mississippi is somehow different from the segregation that exists in other parts of the country because of the state’s unusually violent history. Am I more sensitive to what’s around me because of what we are studying? This is something I’m going to keep thinking about.

page 4 of 5

|

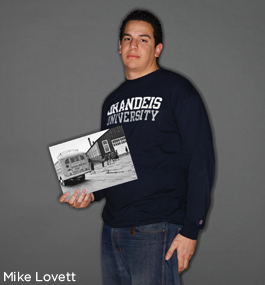

| Jesse Begelfer '11 |

CRIME AND PUNISHMENT

by Jesse Begelfer '11

I was struck this week by French sociologist Émile Durkheim’s idea that the way crime is treated demonstrates to outsiders the boundaries of any society. Who is charged? Who is acquitted? What cases are brought before the court in the first place? In the case of pre-civil rights Mississippi, the police and the court system made it known there would be little punishment of crimes against blacks and their sympathizers. It was “open season” on blacks.

What can we learn about today’s society by examining how the crimes of 50 years ago are prosecuted now? In class we examined the case of Edgar Ray Killen, a Klan member who was convicted in 2005 of manslaughter in the 1964 deaths of three civil rights activists. Though the evidence against him was overwhelming, the jury made it clear that if murder had been the only available charge, Killen would have been acquitted.

I think the charge of manslaughter understates Killen’s crimes. I am not saying the community still condones the crimes committed by Killen all those years ago, but the reduced charge, combined with the fact that some testimony in Killen’s case was available only anonymously even in the early 21st century, persuades me that fear is alive and well in Neshoba County. Although there is a general desire to move forward, there is also a resistance to examining the past.

|

| Edwin Gonzalez '13 |

SEPARATE AND UNEQUAL

by Edwin Gonzalez '13

Today marked our second week of researching in our local field sites. I spent most of my time in the Mississippi Department of Archives and History researching Jackson’s municipal records. Very quickly I came across an interesting holding. Before the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, the Mississippi State Department of Education wrote a report on the condition of schools in the state’s counties. This report was an incredible find.

It included valuations for each of the schools, except for the Negro schools in Neshoba County, which leads me to believe formal valuations were never done for these schools. But in a general effort to circumvent the looming Brown decision by creating “equal facilities” for Negro students, officials proposed to close 18 of the county’s 22 existing Negro schools. To bring the four remaining schools up to the required standards, the county would need to provide, for the first time, basic facilities that white students had long enjoyed, including on-site cafeterias, “satisfactory” classrooms and bus transportation. The fact that these sorts of improvements were required to create even the impression of equality demonstrates the serious educational discrimination that had long existed in the county. I’m excited to see where this finding will take my research, as well as how it might influence other groups’ research.

page 5 of 5

|

| Molly Schneider '11 |

FAITH HEALING

By Molly Schneider ’11

Sitting around a dining room table in Natchez, Miss., one evening, we laughed at the unpredictability of life. Who would have imagined a chance encounter with a bartender at a local pub would lead to one of the most significant experiences of our summer? But after hearing about our research, Chris Townsend offered to introduce us to his mother, who had grown up in Natchez during the turbulent 1960s.

As we sipped sweet tea, Ms. Townsend told us that a local white man had molested her routinely when she was in grade school. But even at such a young age, she knew enough about race relations in Natchez to keep her mouth shut, because if her father confronted the white man it would only mean trouble for her family.

Today, as a hospital nurse, Ms. Townsend sometimes hears older African-American patients whisper in her ear how proud of her they are to see her working in a professional position.

Throughout the interview, I was struck by this woman’s emphasis on religion. While we both believe that hatred is learned and thus can be unlearned, I believe such a process occurs through dialogue and interracial conversation. She, on the other hand, sees reconciliation as the work of Jesus. Somehow, faith has helped her to see the best in people, even when they saw nothing in her.

|

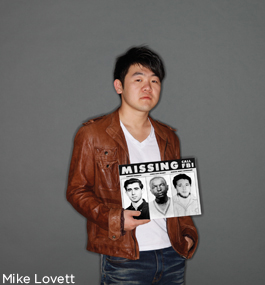

| Yosep Bae '12 |

PROFILES IN COURAGE

By Yosep Bae ’12

I was truly impressed by the courage of civil rights activists 50 years ago in challenging an unjust system. We live in a safer world, where our rights are better protected — today American civil rights activists do not have to worry about losing their lives. Still, I can relate emotionally to the courage of those Mississippi activists because of my experience fighting a gang in my middle school years ago.

Every day gang members would beat up students, and every day teachers would cover up these incidents by looking the other way and not reporting them to the headmaster or police. No students had the courage to stand up to the gang in our school; they believed this unjust pecking order — a few violent students dominating the majority of peaceful students — was inevitable. When I confronted the gang members, I was called the “crazy one in class 13.” Most of my friends were too afraid to be seen with me.

The kind of fear the gang generated in the students perhaps was similar to the threat many felt in the face of institutional violence in pre-civil rights era Mississippi. Even though I knew the gang would never go so far as to kill me, I experienced severe emotional violence. Fear, especially when it shapes people’s consciousness and infects their environment, holds immense power — with or without physical violence.