Has Good Sense Been Voted Off the Island?

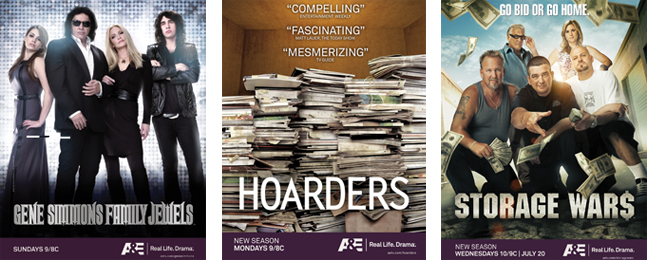

Courtesy A&E Television Networks

by Alex Bloom

What are you watching tonight? A group of overweight Americans sweating through extreme workouts on “The Biggest Loser”? Kim Kardashian in verbal fisticuffs with her mom and sisters? Or brawny Sig Hansen leading the crew of the Northwestern through treacherous waters to find Alaskan king crab?

Over the past decade, reality television — the genre known prosaically within the entertainment industry as “unscripted programming” — has become a prime-time juggernaut, consistently “capturing the largest percentage of the audience watching the top 10 broadcast programs,” according to Nielsen Wire. Midwifed by media consolidation in the late 1990s that forced networks to look for cheaper alternatives to scripted programming, reality TV has edged out the prime-time competition — dramas, sitcoms and sports — every year since 2000.

On the major networks, “Survivor” (CBS), “American Idol” (Fox), “The Bachelor” (ABC), “Dancing with the Stars” (ABC) and “The Celebrity Apprentice” (NBC) regularly showcase people experiencing the throes of rejection, public humiliation, relentless snarkiness and barbed competition — just about every kind of personal smack down imaginable — in the name of keeping it real.

The genre has exploded onto basic cable channels as well. Research has found that 87 percent of all cable programming hours, including news, game shows and sports, is unscripted, says Rob Sharenow ’89, executive vice president of programming at Lifetime Networks and the spearhead of numerous reality shows, including the upcoming 10th anniversary season of the fashion-design show “Project Runway.”

Inexpensive to produce and rich with revenue-generating product placements, reality programming’s appeal is irresistible to TV programmers. But what’s in it for millions of viewers?

“There is raw emotion that viewers see in so much of reality television,” says A&E Television Networks’ senior vice president of talent and production Neil Cohen ’92, whose series “Shipping Wars,” about a group of heavy-duty movers battling for the chance to transport the unshippable, returns for its second season this summer. “There’s a real, visceral, vicarious thrill that they get from watching reality television that they can’t get or don’t get from scripted programming. A little entertainment ain’t a bad thing. I think it’s OK for folks to be able to relax that way.”

Count “Friends” creators David Crane ’79 and Marta Kauffman ’78 among the millions who agree. Crane, whose Showtime comedy series “Episodes” began a second season July 1, admits he’s “a sucker for any show where people can be voted off.” He prefers “American Idol,” Bravo’s cooking show “Top Chef” and “Project Runway.” Kauffman decries shows that exploit human nature’s baser instincts but says she religiously watches Fox’s “So You Think You Can Dance?” and enjoys the Food Network’s cooking competition show “Chopped.”

Gail Shister ’74, a veteran TV critic and columnist for Philadelphia magazine, seems to reflect a general consensus about the genre. “People consider it a guilty pleasure, and there’s nothing wrong with that,” she says. “And because of the way the shows are set up and edited, they produce maximum entertainment.”

“Reality television succeeds because, on some level, it is real,” Sharenow says. “People like to see humanity reflected in the programs they watch. Viewers tune in to be revolted, to laugh, to see something frivolous or to see their lives reflected.” But one thing they don’t tune into is an accurate depiction of reality. “A true reality show would be too boring to watch,” says Shister.

The popular reality shows are often disturbing to watch, says Jennifer Pozner, author of “Reality Bites Back: The Troubling Truth about Guilty Pleasure TV.” She blasts their portrayal of women and minorities, citing as one example a recent lawsuit against ABC for racial discrimination in “The Bachelor” and “The Bachelorette.” Moreover, Pozner says the franchise is built around the premise that single women are pathetic losers who can never have happy or fulfilled lives without a man.

Pozner says another reality program, VH1’s “Flavor of Love,” revived minstrel-show stereotypes for contemporary audiences by portraying women of color as hypersexual, ignorant and violent divas, and men of color as jesters who exist to be mocked. Such shows are “dangerous in that they pretend to be reflecting reality, when instead they depict highly edited and intentionally regressive narratives that prop up certain ideologies — for example, that women have no value beyond their appearance, or that people of color are minstrels or thugs,” she contends.

She points to a 2011 survey by the Girl Scouts of the USA that found that girls who view reality television regularly are more focused on physical appearance, more prone to lying and more likely to expect a higher level of drama, aggression and bullying in their own lives than girls who don’t watch reality television.

“Reality shows are de facto scripted programming,” Shister says. “People are put into made-up situations guaranteed to create conflict, and those scenes are edited to create maximum drama — the more fights, the better; the more screams, the better.”

Kauffman, currently serving as executive producer on a film titled “Hava Nagila (The Movie),” believes some reality television encourages bad behavior. “When you have a [scripted] show about bad behavior, people know what’s fictional and nonfictional,” she says. “When you have a reality show, we’re saying, ‘This is how people really behave, and somehow it’s OK because they’re famous and they’re on television.’”

Cohen and Sharenow concede that programmers sometimes manipulate sound bites and edit footage in a way to create drama where none existed. But Sharenow, who moved to Lifetime last year after helping A&E cultivate top reality shows, says that a show like “Intervention” — where family members step in to try to compel drug addicts to get help — cannot be molded.

“These are shows you can’t manipulate,” Sharenow says. “The stakes are so high.”

A&E’s Cohen cites a recent season of “Gene Simmons: Family Jewels,” which follows the legendary KISS rocker as he mulls over his longtime girlfriend’s ultimatum: marry or split up. People at work would ask Cohen whether a wedding was in the offing. “I had to tell my colleagues over and over again, ‘I don’t know if this is going to happen. This is a real guy. This is a real woman,’” he says, adding that A&E’s brand hinges on authenticity.

Still, authenticity is often in short supply on reality TV. Gorging for more than a decade now on hefty helpings of outrageousness, oddity and ostracism, TV viewers are not sated but desensitized, says Shister.

“The audience is getting so inured to the level of drama and outrageousness that the bar keeps getting higher,” she says. “Viewers need ever greater stimulation to get the same effect.”

Alex Bloom is a freelance writer in Boston.