by Susan Piland

An ordinary object can hold the most extraordinary power.

You’ve experienced it yourself. Going to the Smithsonian and seeing the actual iron wedge Abraham Lincoln split wood with and put his initials on as a young man galvanizes the imagination. In the blink of an eye, Lincoln transforms from textbook fable into flesh and blood.

Similar epiphanies await in the heart of the Brandeis campus. The shelves of the Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department, located in Goldfarb Library, hold countless historical talismans — including many treasures from the realm of fiction writing.

Every scrawl and stain on the small sample of objects showcased in the pages that follow is a reminder that storytellers as celebrated as Fitzgerald, Proust, Heller and Cheever didn’t float to earth with their genius fully formed. They typed up manuscripts they hoped would launch their career, wrote indignant letters to their publisher, inscribed a first edition to a fellow scribbler and painstakingly sketched out a road map for their masterpiece.

Alongside these examples of high art, Brandeis’ extensive collection of dime novels shows us that Americans have always enjoyed a ripping yarn or two, especially when they include the occasional bloodcurdling scream.

So put your feet up, and prepare to be transported — by the magic of 3-D — into the fascinating back pages of literary history.

page 2 of 6

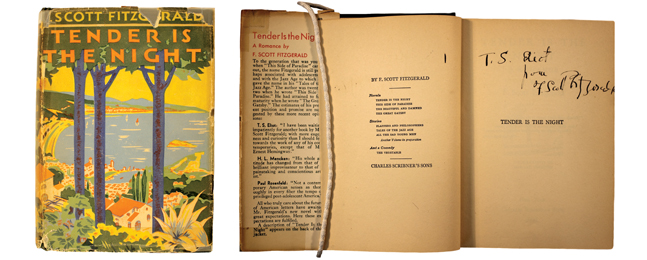

“From F. Scott Fitzgerald”

First edition of “Tender Is the Night” (1934), inscribed by F. Scott Fitzgerald to T.S. Eliot.

The woodblock-print gaiety of the dust jacket is an amuse-bouche, a hint of the luxury that surrounds central characters Dick and Nicole Diver, Americans living on the Côte d’Azur.

But this is Scott Fitzgerald, so you know tragic currents lie beneath that glittering blue sea. “Tender Is the Night” — said to have been the author’s favorite of his four completed novels — contains many parallels to his own failed marriage.

In this particular copy of the book (donated to Brandeis by Louis C. Greene), Fitzgerald autographed the title page for a famous admirer: T.S. Eliot. The poet had already written a flattering blurb for the dust jacket’s front flap: “I have been waiting impatiently for another book by Mr. Scott Fitzgerald; with more eagerness and curiosity than I should feel towards the work of any of his contemporaries, except that of Mr. Ernest Hemingway.”

Improbably, Eliot makes yet another appearance in this edition. Years earlier, after Fitzgerald sent him “The Great Gatsby,” Eliot responded with an exuberant fan letter, calling the book “the first step that American fiction has taken since Henry James.” A slightly edited version of Eliot’s praise appears in the marketing copy on the back of the “Tender Is the Night” dust jacket.

page 3 of 6

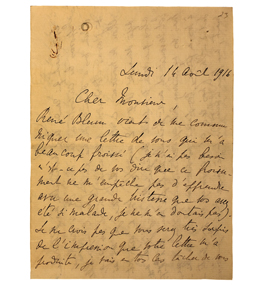

“My Usual Milk”

Letter from Marcel Proust to publisher Bernard Grasset, dated Aug. 14, 1916.

Brandeis owns 23 letters Marcel Proust wrote between 1913-16, which came to Brandeis sometime around 1966 through the efforts of literature professor Milton Hindus (one of the university’s 13 founding faculty members). Twenty-two of the letters are addressed to Bernard Grasset, the man who published “Swann’s Way,” the first volume of Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu.

The working relationship between author and publisher was initially friendly and collaborative. By the time this letter was sent, however, Proust was so angry about delays in the publication of his second volume that he was preparing to move it to another publisher. For 10 pages, in a hand both flowing and crabbed, Proust communicates his dismay and tries to settle up accounts with Grasset.

In the first paragraph, Proust says he writes to air his hurt feelings: “And this shall not be, physically speaking, very easy, because outside of my habitual sickness, I have had, for the last 15 days, as a result of some neuralgic pains of which I do not know the origin (probably dental) a continuous fever which not only prevents me from getting up even for half an hour, but also from taking my usual milk.”

The dispatch is florid, lengthy, precise, demanding and hypnotic. Not unlike À la recherche du temps perdu itself.

page 4 of 6

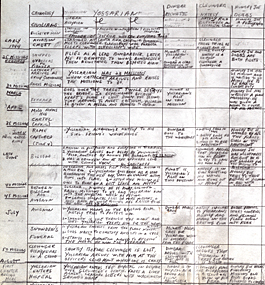

“25 Missions Required”

Character-by-character chronology created by Joseph Heller during the writing of “Catch-22” (1961).

When Joseph Heller gave Brandeis his “Catch-22” materials — including the novel’s manuscript, handwritten on yellow legal-pad paper — the book had been out for only three years, less than half the time it had taken Heller to write it. Special Collections staffers speculate the 1964 gift was prompted by Leo Jaffe, a member of the Brandeis Board of Fellows who was also the president of Columbia Pictures, which at the time held the movie rights to the novel.

This chart (only a portion of which is shown here) is a keystone in the “Catch-22” documents, revealing the careful planning that went into a satire on the randomness of war. In pencil, Heller detailed the novel’s events in a vertical column on the far left, then listed major World War II events in a column on the far right. In between these two poles, he developed corresponding plotlines for each of the major characters. (Yossarian, the reluctant bombardier, commands three columns, so pivotal a figure is he.)

The flight plan paid off — not only did “Catch-22” become a popular synonym for a bureaucratic double bind, the book is ranked No. 7 on the Modern Library 100 Best Novels list.

Manuscript page copyright © 1935, 2013 by John Cheever, used by permission of The Wylie Agency LLC.

page 5 of 6

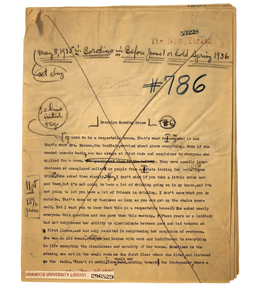

“It Used to Be a Respectable House”

Manuscript for “Brooklyn Rooming House,” by John Cheever. Published in the May 25, 1935, issue of The New Yorker.

“Brooklyn Rooming House” was the first John Cheever short story to appear in The New Yorker, published just days before the author’s 23rd birthday. Likely inspired by his own mother’s painful tumble from gentility into financial worry, the story is a character study of a teetotal landlady who, to her horror, is reduced by the Depression to taking in drunken lodgers.

In all, Brandeis owns the typescripts for 88 Cheever short stories, along with the manuscripts of his first three published novels. Cheever began giving materials to the university in the early 1960s. Louis Kronenberger, a Brandeis librarian and theater arts professor, was a Cheever friend, perhaps providing the impetus for the gifts.

The six-page “Brooklyn Rooming House” manuscript has been marked up by a New Yorker editor for typesetting. Only a few text changes have been made, mostly punctuation and spelling fixes, including the correction of one interesting slip: A staircase, the psychologically fragile author had written, “winds its way torturously,” instead of “tortuously.”

page 6 of 6

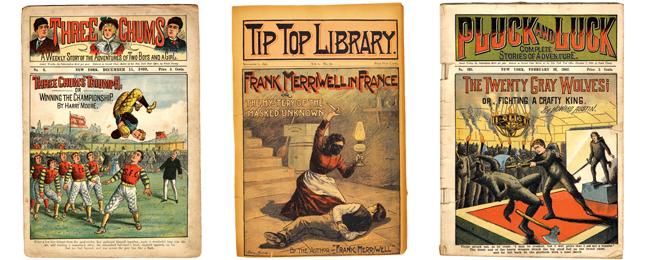

“The Mystery of the Masked Unknown”

Three dime novels, 1896-1902.

Brandeis boasts a large collection of more than 1,000 dime novels, which offers a lively look at 19th-century tastes in fiction.

Edward Levy was the major donor behind this treasure trove. A carnival worker, theater operator, lawyer, banker, editor and publisher, he was also a lifelong collector of dime novels and the first president of the Brandeis Bibliophiles, a group of book enthusiasts who acquired rare materials for Goldfarb Library. Levy made at least two substantial dime novel contributions to Brandeis, which were then supplemented by large donations by Edward T. LeBlanc; Victor Berch, MA’66, the university’s first Special Collections librarian; and several other sources.

The dime novel’s heyday stretched from the 1860s to about 1900, when the cost of a “full-size” novel could run upward of $1.50, putting it out of reach of many readers.

So the dime novel (which, as you’ll notice here, often went for a nickel) filled the gap nicely. New mass-production printing technologies kept prices down, and a lack of copyright laws even allowed publishers to use the dime-novel format to reprint literary classics.

But mostly, as these examples attest, the dime novel’s content was middlebrow at best. Plots were formulaic, characters recurring, and thrills and chills abundant. Until they were replaced by movies and pulp-fiction magazines, dime novels were a high-energy source of roller-coaster story lines and unfailingly happy endings.