The Mother Lode

With a soul-baring third novel, Jennifer Gilmore ’92 comes of age.

Mike Lovett

by Adrian Harris Forman ’92

Though her hip Brooklyn address and teaching positions at Princeton and Barnard might lead you to expect otherwise, novelist Jennifer Gilmore ’92 isn’t the least bit squeamish.

“Where is the blood on the page?” she says she asks herself when she reads fiction, both her own and others’. Where are the difficult moments that “viscerally affect us and make us want to read”?

When Gilmore decided to write a novel about adoption, a process she and her husband were intimately familiar with, she says she originally planned to look at “race, class and the sanctioning of motherhood.” Instead, she wrote a story that is much more raw, a wrenching look at want and wanting.

“The Mothers,” released in April, has received wide-ranging critical acclaim and attention, including from The New York Times Book Review and NPR’s “Fresh Air.” Because the twists and turns of the adoption story lived by main characters Jesse and Ramon echo those experienced by Gilmore and her husband, Pedro Barbeito ’92, many have speculated the novelist has blurred the lines of fiction and memoir.

No, Gilmore insists. Although there are “very real and deep parallels” between herself and Jesse, she says any attempts to conflate the two lives are, at best, misleading. “Fiction is the lens through which I view the world,” she explains.

Yet because Jesse’s story so closely parallels the author’s struggles — an almost obsessive desire to become a mother, the failed efforts to have a biological child, the pursuit of an open adoption — telling Jesse’s story was not easy for Gilmore. It required growth, both personally and creatively.

In her own write

When I first met Gilmore at Brandeis in the early 1990s, we were English majors sharing the same adviser. Sylvia Plath was the subject of her senior thesis. I had thrown myself into the work of Anne Sexton. Bonding over suicidal poets might have been an unusual way to begin a friendship, but we were full of edgy Generation X cynicism, and the personal and professional lives of these groundbreaking women fascinated us.

After Brandeis, I packed up for the University of Pennsylvania to get an MA in English language and literature. Gilmore headed off to Cornell for an MFA in fiction, and went on to teach creative writing and literature at schools around the New York City area and write successful novels. Over the years, we have moved in and out of each other’s lives, thanks in no small part to our husbands, who have also been friends since Brandeis.

In her novels, Gilmore explores social and personal dilemmas that defy simple solutions. Her debut book, “Golden Country” (2006), imagines the lives of Jewish immigrants in New York during the early to mid-20th century. “Something Red” (2010) lays bare the anxieties of second-generation, suburban Jewish America, examining social change and student activism on the Brandeis campus in 1979.

Focusing her third novel on adoption not only allowed Gilmore to look at the adoption process as an anthropologist might, as something outside her own personal experience, it also led to a fundamental shift in her writing. For the first time, she says, she felt compelled to write fiction in the first person.

page 2 of 3

The sure thing

The narrator in “The Mothers” is Jesse, who, like Gilmore, is a teacher in her late 30s living in New York City. Having had cancer as a young adult, Jesse finds she’s unable to have children; she and Ramon pursue open adoption after exhausting the medical route. (“Ramon had wanted out of the science [of in-vitro fertilization] before we’d even begun,” Jesse says, “believing my body, which had undergone surgeries and chemo, had withstood enough.”)

Like Jesse and Ramon, Gilmore and Barbeito tried to have children of their own, eventually deciding, Gilmore says, that they could no longer pursue “medical interventions that might work out.” Instead, they turned to adoption — the sure thing that proved to be anything but.

In nonfiction pieces for The New York Times, Vogue and The Atlantic, Gilmore has described the incredible highs and lows she and her husband experienced during their adoption process. Being rejected at the 11th hour by a birth mother. Learning that the healthy infant you thought you were adopting is, in fact, a baby with significant special needs. Being emotionally blackmailed by women who present themselves as birth mothers but are not pregnant.

No one who sets out to become a parent knows what will happen, Gilmore observes: “You just don’t know if it will be easy or hard.” Then, with understatement that takes my breath away, she says, “It turned out to be hard for us.”

She rejects the idea that writing “The Mothers” was therapy. “My adoption experience is so much longer than Jesse’s,” she says. “I could not be taught by her. Maybe I could teach her. It was really hard to write a book where I did not know what the adoption ending would be, much less all the smaller endings. As a novelist and as a person also, you want a beginning, middle and end. I had to accept I didn’t have that.”

Though I knew some of the ups and downs of Gilmore’s adoption efforts before she wrote about them, I have found it almost impossible over the years to ask her more than the simplest questions about what the experience was like. I was afraid of asking the wrong way. I think I feared the answers even more. I have two boys, whom Gilmore has watched grow up. I have felt guilty, and, as silly as it sounds, I have wanted to apologize that I was able to become a mother so easily.

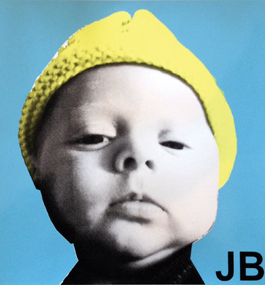

Pedro Barbeito

BABY FACE: Gilmore’s husband, artist Pedro Barbeito ’92, created this silk-screen portrait of the couple's son.

page 3 of 3

When she and I discuss “The Mothers,” I am finally able to ask her to tell me at what point she and Barbeito decided to adopt. “It was part of a process,” Gilmore says. She and her husband embraced the dream inherent in the way adoption professionals talk to prospective parents: You will have a baby. The question is “when,” not “if.”

What’s left unsaid is the toll the adoption journey can take on those who embark upon it.

“Most adoption narratives are about what happens after you get the child,” says Gilmore. “The Mothers,” on the other hand, is about “the tragedy before the adoption.”

“A collection of bees”

The novel is colored by larger societal questions as well, such as “what happens to all these birth mothers?” Gilmore says. “What happens to the children you don’t get to adopt? You can never know all the endings. So many of these adoption stories — even the ones that end with children in their adoptive homes — you still don’t know the ending. It defies storytelling.”

Gilmore’s family encouraged her as she wrote. “Pedro is an artist, too,” she says, “and he is glad that I took something so painful for me and for us, and turned it into something else. My parents, who are not artists, are also supportive.”

Though the book could easily have foundered under the weight of its themes and Jesse’s often heartbreaking voice, Gilmore buoys her narrative with biting humor. Jesse is funny, smart and bracingly honest about her longing to be a mother, like when she dissects her behavior at a weekend retreat for adoptive parents: “I did what I could not help, which was infuse absolutely everything with magical thinking. If we arrive on time for each event this weekend, we are that much closer to being parents. If we are late? Well, who knows what that means for our file. Perhaps lateness — along with being a bad baker, say, or cursing — would make becoming parents impossible.”

Gilmore understands humor’s transformative power. “The Jews have always used humor to survive,” she says. “You can write the most serious thing in the world, but if you infuse it with humor, you can say anything.” Jesse’s sense of the absurd even leads her to question the wisdom behind open adoption: “You catch more bees with honey than vinegar, but who the hell wants a collection of bees?”

Finally, in January, after years of waiting and hoping, Gilmore and Barbeito welcomed a baby boy into their lives through an open adoption. Becoming a mother just weeks before the publication of “The Mothers” seems a storybook ending for Gilmore, and a beginning.

When asked how she feels about open adoption now, she pauses and says, “When it works, open adoption is the best thing for the child, the birth mother and the adoptive parents, because of the transparency. What I am not in favor of is the process, which is hard to navigate.”

Now that she has a few months of parenting under her belt, I mention that many women (myself included) come away from giving birth saying, “No way. Never again.” I ask if she thinks adoption could be the same sort of thing.

Gilmore laughs and says, “I was recently listening to a radio show about what you need to know if you are adopting, and I thought, Oh, my God, I cannot believe what we went through. We are just starting to be able to think about everything that has happened. I have a few friends who are having boys this fall, and I’ve been thinking about how I will have hand-me-downs soon for them.”

That reminds me: I have some hand-me-downs for her son, too.

Adrian Harris Forman ’92 is a freelance writer in Hastings-on-Hudson, N.Y. She can be reached at adrianhforman@gmail.com.