How the Bible Became the Bible

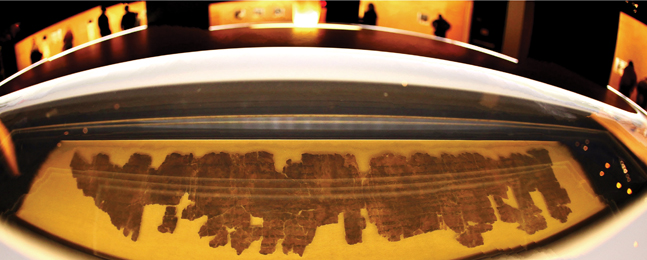

Darryl Moran / The Franklin Institute

by Leah Burrows

For 2,000 years, the earliest-known copies of Genesis, Exodus, Psalms, Isaiah and other ancient writings lay hidden in a series of caves overlooking the Dead Sea. Discovered between 1947 and 1956, the Dead Sea Scrolls comprise some 972 remarkably well-preserved texts — one of the most significant archaeological finds of the 20th century.

Now, in a rare exhibition at the Museum of Science, Boston, on view through October 20, the scrolls and related artifacts offer a glimpse into an influential Iron Age culture and the Second Temple period. And in an unusual partnership, Brandeis faculty (who made suggestions to the museum regarding which scroll fragments to exhibit) and students are collaborating on educational programming to enrich visitors’ encounters with the scrolls. Events include faculty lectures on and off campus, a campus music concert inspired by scroll texts, and a physics department colloquium that will discuss electronic and spectral imaging in archaeology.

Says Marc Brettler, MA’78, PhD’87, the Dora Golding Professor of Biblical Studies and chair of the Dead Sea Scrolls committee, “The Dead Sea Scrolls are important missing links. They help us understand how the Bible became the Bible, and demonstrate how little Hebrew script has changed over the past 2,000 years.”

The scrolls let us into the minds of ancient people, contends Jamie Bryson, a PhD student in Bible and ancient Near East. “Nothing can tell us more about humanity than people’s thoughts and writings,” says Bryson, an intern at the Museum of Science this summer. “Though they are ancient, the scrolls never get old.”