Hard Truth-Telling

The black revolution came to Brandeis in 1969 when students demanded the creation of a black studies department. Ever since, African-American students and faculty have held Brandeis accountable to its ethos of equity and justice.

Getty Images

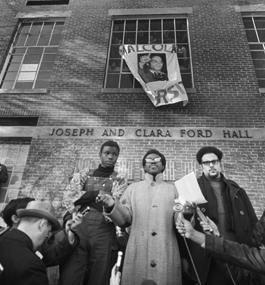

TAKING A STAND: Reggie Sapp '73, MA'05; Lloyd Daniels '69; and Randal Bailey '69 read the Ford Hall protesters' demands in January 1969.

by Chad Williams

The protesters’ first demand was explicit and nonnegotiable: the creation of an “Afro-American and African studies department with the right to hire and fire.”

On the wintry afternoon of Jan. 8, 1969, between 60-75 black and Latino/a students began an occupation of Ford Hall, Brandeis’ main academic building, where the university switchboard was also housed. The students issued a list of 10 demands and vowed to remain in Ford Hall until all

were fully met.

The black revolution had come to Brandeis, and the university was suddenly paralyzed. Given its unique history of openness to men and women of all backgrounds, ethnicities and faiths, Brandeis had viewed itself as different. Race was not seen as a problem. Now, dramatically, the needs and future of black students had become a concern. Fear and uncertainty gripped the campus. What would happen? How would the administration respond? Would there be violence?

When the student protesters ended the occupation 11 days later, the university had agreed to create the Department of African and African-American Studies at Brandeis, one of the first academic departments of its kind in the country.

University curricula had marginalized or flat-out ignored the experiences of people of African descent. By focusing on the history, politics and culture of black people, black studies departments like AAAS sought to prove black studies’ legitimacy as a scholarly endeavor. Proponents at Brandeis, in 1969 and today, believed all students, regardless of race, should be exposed to black studies as part of their educational experience.

Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department, Brandeis

RIPPLE EFFECT: Students gather outside Ford Hall during the '69 protest

page 2 of 8

The unique story of the university’s African and African-American studies department, which celebrates its 50th anniversary in early 2019, mirrors the equally remarkable history of black people at Brandeis. Like AAAS itself, the experience of black students, faculty and administrators is one of perseverance in the midst of isolation, struggle in the face of indifference, and academic excellence in spite of the slow pace of progress and university support.

Above all else, the intellectual and institutional work of AAAS and black people at Brandeis has made the university what it is today: a place of critical learning that embraces the challenges of creating an equitable and more humane world. Indeed, AAAS has held and continues to hold the university accountable to its commitment to social justice and its credo, “Truth Even Unto Its Innermost Parts.”

‘One of those spasms of history’

From its beginning, Brandeis was a daring experiment and a bold statement. In the wake of World War II, and at a time when Jews; African-Americans; and other racial, ethnic and religious groups faced systematic exclusion from many of the nation’s top universities, Brandeis presented itself as a haven for truth, openness and critical learning, rooted in an institutional obligation to repair a broken world.

It was fitting that Ralph Bunche, H’60, the noted African-American scholar, diplomat and future Nobel Peace Prize recipient, who had recently negotiated the armistice agreement ending the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, was the university’s first convocation speaker. “There is much to be done in our world,” he told the audience on Sunday, June 21, 1949. “But in a democracy, what needs to be done can be done if the people are alert and determined.”

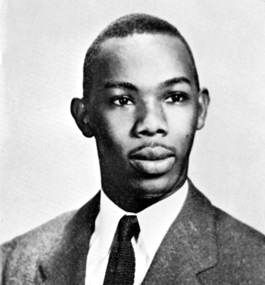

Bunche was a role model for the university’s first black graduate, Herman Hemingway ’53, who was offered full scholarships to Harvard, Boston College and Brandeis before choosing the latter university, then only a year old, because it was “innovative and exciting.” (During Hemingway’s first year, he was a fraternity brother to Martin Luther King Jr., then a Boston University graduate student.)

Herman Hemingway '53 (in a Brandeis yearbook photo).

page 3 of 8

Well before AAAS existed, Hemingway was helping to lay its foundation, linking academics to the fight for racial justice. Hemingway established a chapter of the NAACP at Brandeis and pushed his classmates to connect the challenges facing African-Americans to their own lives. “We saw the inequities that existed around us,” he recalled in a 2013 interview. “You can’t stick around and see that without trying to do something about it. Otherwise, you’re responsible for it.”

After the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision declared segregation in public education unconstitutional, Brandeis began to play an important role in the civil rights movement. Prominent black activists and intellectuals came to campus to speak and engage with the Brandeis community. On Nov. 12, 1956, King made the first of three visits. Langston Hughes, Roy Wilkins and James Baldwin spoke on campus as well.

The number of black students, however, remained in the single digits. During her four years at Brandeis, future scholar and activist Angela Davis ’65 could count the number of fellow black students on one hand. Now Distinguished Professor Emerita at the University of California, Santa Cruz, Davis says her Brandeis experience — especially a 1963 campus visit by Malcolm X — shaped her intellectual and political consciousness. Nevertheless, as she recalled in her 1974 autobiography, during her time on campus the “physical and spiritual isolation were mutually reinforcing.”

King’s assassination on April 4, 1968, marked a turning point for the nation and for Brandeis. In a letter to The Justice, Patricia Hill Collins ’69, PhD’84, captured the feelings of many black students. “I did not and cannot forget the sorrow of that moment as all black Americans now and this summer will never forget,” she told her white classmates. “We cannot settle back into our comfortable ruts, for our lives never have been and now are doomed never to be ‘comfortable’ like yours.”

Black students didn't’t just let their discomfort be known, they mobilized to make Brandeis a truly welcoming institution. The Afro- American Organization issued a series of proposals to President Abram Sachar that led to the creation of the Transitional Year Program, for promising students who had limited precollege academic opportunities (renamed the Myra Kraft Transitional Year Program in 2013); Martin Luther King Jr. scholarships; and more financial aid for black students. As a result, the number of black students enrolled in fall 1968 more than doubled the number enrolled the previous year. Brandeis’ first female African-American professor, Pauli Murray, also began teaching that semester.

When spring semester arrived, Brandeis found itself, as Murray recalled in her memoir, in “one of those spasms of history.” Black Power-inspired student protests had already gripped Cornell, Columbia and San Francisco State. Brandeis was next up in the wave of black student protests that swept the nation in 1968-69. And although Brandeis considered itself a place of racial liberalism, with Jews the traditional allies of African-Americans, black students would show the university that it was not immune from institutional racism and force it to re-examine its very character.

The first group of black students entered Ford Hall around 2 p.m. They told the two operators in the switchboard room to leave. As more students joined the occupation, they went room to room announcing the end of classes and demanding that faculty and staff exit the building. By evening, after a series of emergency meetings, the university administration and most of the faculty had condemned the occupation, with new President Morris Abram expressing his “deepest shock and amazement over this student act.”

Of the 10 demands publicly announced on the occupation’s first day, the most radical and forward-thinking was the creation of an African and African-American studies department. Roy DeBerry ’70, MA’78, PhD’79, was chairman of the Afro-American Organization and a lead spokesman for the Ford Hall protesters. The university had previously agreed to the creation of concentrations in African and African- American studies. But as DeBerry and others astutely recognized, these could eventually be eliminated; a department, however, would be an integral part of the institution. Most important, it would have the power to hire its own faculty, determine its own curriculum and, ultimately, shape its own future.

Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department, Brandeis

SIGNS OF SUPPORT: Outside the Ford Hall Occupation.

page 4 of 8

“The university did not think black students were worthy of a department,” DeBerry remembers. “They also did not see black studies as a legitimate discipline.” On Jan. 13, the occupying students renamed Ford Hall “Malcolm X University” and began holding classes of their own.

That same day, the faculty voted to approve the creation of the AAAS department on the condition that Ford Hall be vacated. The protesters held firm and continued negotiations — which were at times tense — with Abram and the administration over the department’s structure and resources, and student influence over the department’s future. The occupation ended on Jan. 18 when the Ford Hall activists received a promise of amnesty and pledged to “continue our struggle to gain effective control of the Afro-American studies department to be established here.”

On April 24, after more negotiations between students and administrators, the Brandeis faculty formally approved the creation of the AAAS department. Ronald Walters, a political scientist and specialist in African studies and international affairs, was appointed the department’s first chair. With no precedent to guide its implementation, either at Brandeis or nationally, the department now had to prove its credibility. “What is important,” Walters said when he arrived at Brandeis, “is that Afro-American studies has the same opportunity to develop intellectually as other academic fields.”

AAAS offered its first courses in fall 1970. The initial curriculum consisted of 20 courses, including core offerings like “Introduction to Black Studies,” “Black Historical Tradition,” “African History” and “Black Literature.” In addition, the department developed novel courses like “Imperialism and Protest,” “Black Lifestyles Through Music,” “The Black Family” and “Black Political and Social Thought.” The courses reflected the excitement and challenges of creating not just a department but an entire discipline from scratch. AAAS immediately transformed what Brandeis students could be exposed to in the classroom.

Curtis Tearte ’73, now a member of the university’s Board of Trustees, remembers the intellectual energy surrounding the department. “I stood on the shoulders of those that made AAAS a reality,” he proudly reflects. In his AAAS courses, Tearte says, he developed a “clarity and understanding” about African- American history and culture, and the politics of the times, which would shape his future as an IBM executive and philanthropist.

‘The hub of black culture’ on campus

Yet even as the department quickly became central to the experience of many black students, tensions around AAAS’ legitimacy as a separate discipline continued. These tensions mirrored broader debates about the integration of African-Americans into society in the wake of the civil rights movement.

Julieanna Richardson ’76, H’16, who came to Brandeis “in total anticipation of a new place,” recalls swirling questions about the future of the department and whether “it was going to be part of the larger university.” She would later learn her adviser, American studies professor Lawrence Fuchs, hoped to have AAAS subsumed under his department.

Angela Davis '65 (during a 1987 visit to campus).

page 5 of 8

With the university devoting minimal resources to AAAS and some faculty working to thwart its success by arguing that black studies should not be a separate academic entity, many expected the department to fail. Instead, it took an important step toward long-term viability when Wellington Nyangoni, a renowned scholar of African politics, was appointed chair in 1976. Three years later, Nyangoni became the first black professor to receive tenure at Brandeis.

Despite a small faculty and limited resources throughout the 1980s, the department forged ahead. It continued to offer a necessary corrective to a campus that largely ignored the study of people of African descent, then a pervasive problem at American universities. The department’s impact extended beyond the classroom as well. Darrell Gaskin ’83, P’18, was like many black students who experienced culture shock when they arrived at Brandeis. AAAS, he recalls, served as “the hub of black culture” on campus, with department-sponsored lectures, receptions and performances creating a space for black students, faculty and staff to come together. AAAS was also a center of political activism, especially around the anti-apartheid and divestment movements that riveted the campus.

Evelyn Handler, president of Brandeis from 1983-91, worked to bring greater diversity to the student body and faculty, and voiced her support for AAAS. In particular, she hoped to improve the social and educational experiences of students of color, and saw AAAS as playing a key role in that effort.

Yet Ibrahim Sundiata, a professor who joined the department in 1990 and later served as chair, says his experiences were sometimes like “walking up the downward staircase,” as support for the department remained tenuous. “I never doubted Brandeis’ long-term commitment to diversity,” he notes. Nonetheless, he saw the difficulty the university faced in translating words into action.

Over the years, under the leadership of Nyangoni, Sundiata and associate professor Faith Smith, a specialist in Caribbean literature, the department’s presence and impact continued to far outweigh its small size. Students from many backgrounds enrolled in AAAS courses. The faculty were widely recognized as experts in their respective fields, publishing nationally and internationally heralded books. On campus, the department provided essential leadership on issues of diversity and racial injustice through official committee work, and informal advising and mentorship.

AP Photo/Frank C. Curtin

RESOLUTE: Inside Ford Hall. Ricardo Molett; Bob Jones '71, MA'75; and Roy Deberry '70, MA'78, PHD'79, talk with the media.

page 6 of 8

Then came the 2008 financial crisis, which hit Brandeis hard, nearly claiming AAAS as a casualty. A Curriculum and Academic Restructuring Steering committee, one of several groups formed to make Brandeis more financially efficient, recommended transforming the classics, American studies and AAAS departments into interdepartmental programs. The committee noted AAAS’ small size and called its structure, with only a limited number of core faculty, “not optimal.”

The CARS committee’s recommendation was seen as an attempt to erase the legacy of the Ford Hall occupation, and vigorous protests began immediately. Both the faculty and the Student Union Senate formally opposed the change. As they did in 1969, students led the charge, arguing the department should not be punished for the university’s long-standing lack of support. If Brandeis had truly committed to and invested in AAAS, they argued, there would be no need to transform it. In a Justice editorial, AAAS major Nathan Robinson ’11 wrote, “AAAS is not expendable, and Brandeis cannot simply wipe the struggles of its black students from the pages of its history.”

In response to the widespread outcry, the CARS committee reversed course. A May 4, 2009, supplemental report recommended that “AAAS remain a department, but one with significantly increased faculty participation in its major.”

The university administration now added material support to their rhetorical backing of AAAS. I was appointed department chair in 2012. The department’s budget began to increase incrementally. The dean of arts and sciences supported a cluster-hire initiative in African diaspora studies, which resulted in a number of new faculty hires in partnership with women’s, gender and sexuality studies; history; English; education; and sociology. AAAS increased its visibility through more robust programming and collaborations across the university.

A sense of energy and excitement surrounded the department. Guests such as writer Ta-Nehisi Coates, artist Mark Bradford and cultural critic Margo Jefferson ’68 visited campus. New classes energized students and significantly increased the number of AAAS majors and minors. “Black Feminist Thought,” for instance, a course offered by faculty members Jasmine Johnson and Aliyyah Abdur-Rahman, served as an important communal and intellectual space for students seeking to make sense of their identities at Brandeis and in the larger world.

For students, AAAS professors were “models of how to not only exist but thrive in this world,” says Aja Antoine ’17, an AAAS and sociology double major. “We were learning about systems but also creating systems of care and belonging.”

Mike Lovett

Faith Smith, associate professor in the AAAS and English departments.

page 7 of 8

Where critical learning and political consciousness meet

In late 2015, inspired by the #BlackLivesMatter movement, students on college campuses across the country, starting with the University of Missouri, began to protest institutional racism and call for systemic change.

At Brandeis, AAAS students once again put their classroom knowledge into practice. On the warm afternoon of Nov. 20, Brandeis students began what would become a 12-day occupation of the Bernstein-Marcus Administration Center. The students named the protest #FordHall2015 to honor the 1969 activists and explicitly stake claim to a historical continuum of black struggle at Brandeis. Among their 13 demands were the hiring of more black faculty, curriculum development around issues of race, diversity and inclusion training for current faculty and staff, and an increased minimum wage for Brandeis employees.

AAAS students and faculty played key roles in #FordHall2015. Students transformed Bernstein-Marcus into a place of political consciousness and critical learning. AAAS faculty used their classes to raise awareness about the protest and connect it to their subject matter.

The occupation ended on Dec. 1, with the university agreeing to implement a number of measures to improve the social, cultural and academic life of students of color at Brandeis, and to accelerate the pace of its stated commitment to diversity and inclusion. Brandeis hired its first chief diversity officer, Mark Brimhall-Vargas, in 2016, and two years later recruited Allyson Livingstone as its first director of diversity, equity and inclusion education, training and development. The university has also stepped up efforts to attract more underrepresented faculty, staff and students of color.

Mike Lovett

REDUX: #FordHall2015 activists take up the call for progress, 46 years after the protest that inspired their effort's name.

page 8 of 8

Today, AAAS is one of the most vibrant academic departments at Brandeis. Its classes are cutting-edge, and its programming intellectually stimulating. It continues to produce remarkable students like R Matthews ’19, an AAAS and computer science double major, who has emerged as one of Brandeis’ most recognized student leaders. “AAAS has given me community,” he says. “It has also given me language to describe certain things I had been trying to figure out for a long time.”

Recent AAAS majors like Natasha Gordon ’15 and Alexandra Thomas ’18 have written award-winning senior theses and gone on to attend graduate programs at top schools like Yale; the University of California, Berkeley; and Cornell. The scholarship of faculty members like Carina Ray, Wangui Muigai and Amber Spry has eliminated any lingering doubts about the legitimacy of AAAS as a discipline.

Across the U.S., African and African-American studies programs and departments continue to face challenges. University budgets are becoming more constrained, and the current political and racial climate is filled with challenges to the idea that learning about the black experience is important.

But if past is prologue, AAAS students and faculty will remain on the front lines at Brandeis, demanding that principles of fairness, intellectual honesty and justice prevail. Through their efforts, the department’s next 50 years should prove as historic and meaningful as its first.

Chad Williams is the Samuel J. and Augusta Spector Professor of History and African and African-American Studies, and chair of the Department of African and African-American Studies.