The Art of Disruption

The Rose Art Museum’s 60th anniversary exhibition upends the traditional blockbuster-show narrative, pairing modern icons with historically marginalized artists for a look at the past that reveals the museum’s plans for its future.

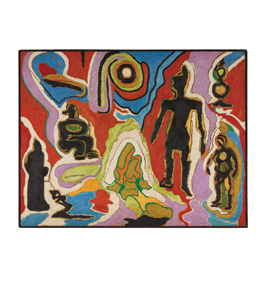

Photo by Mel Taing, 2021. Courtesy of the Rose Art Museum.

Gallery view of “re: collections, Six Decades at the Rose Art Museum”

by Julia M. Klein

It is midday on a broiling hot Saturday in late June. Gannit Ankori, too busy to have eaten dinner last night or breakfast today, is starving. But she still summons the energy to joyfully welcome visitors who have found their way to the Rose Art Museum, where she is the Henry and Lois Foster Director and chief curator.

For the Rose, as for the rest of Brandeis and the world, it has been a year like no other: lockdowns, shifting COVID protocols and, not least, the challenges posed to the cultural status quo by the ongoing racial reckoning. After all this, plus seemingly endless Zoom meetings and supply-chain delays, Ankori and the Rose finally have cause to celebrate: the opening of a pair of exhibitions — one spotlighting the museum’s permanent collection of more than 9,000 works and another on Mexican artist Frida Kahlo — in time to mark the museum’s 60th anniversary this year.

The first of the two exhibitions, “re: collections, Six Decades at the Rose Art Museum,” is the official anniversary show, pairing iconic works by such figures as Pablo Picasso, Willem de Kooning and Andy Warhol with lesser-known pieces and newer acquisitions, including works by women, LGBTQ artists and artists of color. This loosely thematic installation will run for three years, with rotations and additions made every six months or so.

Ankori, who is also a professor of fine arts and women’s, gender and sexuality studies, says the show attempts to disrupt the familiar master narrative of art history by “suggesting different juxtapositions, new dialogues and alternative genealogies of art.” The exhibition pays tribute to what she calls the Rose’s “groundbreaking history” as a pioneering venue for contemporary art, while also examining that history through a critical lens, noting its omissions, and “looking forward to where we go from here.” The show’s title, a play on the words “collections” and “recollections,” points to that duality.

The exhibition, says Ankori, is just one marker of the museum’s intent to transform itself into an anti-racist institution, dedicated to diversity, equity and inclusion in staffing, audiences, management practices, collecting and interpretation. Highlighting previously underrepresented artists — and critically challenging and undoing their lack of representation — is perhaps the most visible component of this effort.

“That’s reparation,” Ankori says. “That’s social justice work. But it is also of huge importance for the museum and our visitors in artistic terms. This curatorial project offers a deeper, broader, more inclusive and more diverse experience of human creativity.”

Mike Lovett

Gannit Ankori

page 2 of 9

Provocative echoes and contrasts

The arrangement that opens the anniversary exhibition — which Ankori co-curated with Caitlin Julia Rubin, the Rose’s associate curator and director of programs, and Elyan Jeanine Hill, guest curator of African and African diaspora art — signals the show’s ambitions.

Beauford Delaney’s vibrant painting “Abstraction (Greene Street)” (1950) hangs between Picasso’s 1934 canvas “Reclining Nude” and Gauguin’s 1894 bronze sculpture Tahitian Figure. The commonalities between the Delaney and the Picasso are immediately apparent. “They share a color scheme, and an oscillation between figuration and abstraction,” Ankori says.

But the juxtaposition also makes another point. Though “Abstraction (Greene Street)” has been in Brandeis’ collection since before the Rose’s 1961 founding, it has never before been on display at the museum. An important figure associated with the Harlem Renaissance and a mentor to James Baldwin, Delaney “remained on the margins of society for most of his life,” Ankori says. “He was a gay African American artist who, tragically, died in a Paris asylum, penniless. In this show, we’re putting him on equal footing with Picasso, creating a dialogue between their paintings. We’re also raising questions about the exclusion of such a brilliant painter from the canon.”

And the exhibition sheds new light on the brand-name artists. The labels explain that Picasso, at 53, was painting his 17-year-old mistress and mother of his child, and that, while in Tahiti, the middle-aged Frenchman Gauguin took a native 13-year-old girl as a “wife.” “We provide information,” says Ankori, “and viewers can assess the quality of the art. But they can also think about Picasso’s and Gauguin’s attitudes toward teenage girls, and about acceptable representations of women as objects of sexual desire.”

The entire “re: collections” exhibition, which fills three galleries, offers an array of similarly provocative echoes and contrasts. The show’s themes include the tension between representation and self-representation; the impact of historical traumas; fragmentation and reconstruction; and the depiction of new worlds. (The exhibition design is by Isometric Studio, a Brooklyn-based minority-owned firm that, according to its website, aims to “advance an ethos of inclusion, equity and justice.”)

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. Photo by Tim Lanterman for the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art.

Betye Saar, Supreme Quality, 1998. Mixed media on vintage washboard and tub.

page 3 of 9

A recurring trope in the first gallery is the stereotypical Black mammy figure, marketed for years by such businesses as Aunt Jemima (now Pearl Milling Company), and reclaimed and transformed by artists of color. In a recently acquired mixed-media piece, Supreme Quality (1998), Betye Saar depicts a gun-toting mammy figure on a washboard — a domestic worker turned warrior. Saar “rehabilitates a negative, racist and misogynist image, and transforms it into an empowering work of art,” says Ankori. And, she adds, in calling attention to the under-compensated manual labor of Black women, Saar comments not just on race and gender, but on class.

The centerpiece of the second gallery, which focuses on historical traumas, is Radcliffe Bailey’s newly acquired 2007 sculpture Storm at Sea, a representation of the Middle Passage, the forced voyage of enslaved Africans across the Atlantic to the New World. On a metaphorical sea composed of broken piano keys sits a replica of a sculpture used in Yoruba dances and the model of a ship. Guest curator Hill says the piece evokes “a sea of bones, a bridge of bones, a connection that’s being made to history.”

Serving as a portal to the third and largest gallery is a curtain composed of colorful strips of canvas. The artist Mark Bradford describes this 2015 piece, Waterfall, as “detritus from another project.” Nearby is Fred Wilson’s sculpture The Beginning of the End (2009), which Ankori calls “a cascade of black glass teardrops” pooling on the gallery floor. Al Loving’s “Self-Portrait” (1973) mirrors the Bradford in its use of canvas from previous works — shredded, dyed and reconstructed into an artifact that references African American quilts and the collages of Romare Bearden.

The exhibition prominently features quotes from the artists themselves. “We try to let the artist’s voice be primary,” says co-curator Rubin. “We want the Rose to be a space where knowledge is created collectively, communally, collaboratively, and it isn’t something that’s handed down.” Eventually, she says, the curators hope to incorporate the responses of visitors as well.

“Re: collections” flows directly into the smaller loan show “Frida Kahlo: POSE,” co-curated by Ankori and Circe Henestrosa, an Indigenous Mexican fashion scholar and curator. On view through Dec. 19, the exhibition features an array of vintage photographs, as well as paintings, works on paper and ephemera. Rare film footage shows Kahlo with her husband, the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, and one of her many lovers, the Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky.

Photo by Mel Taing, 2021. Courtesy of the Rose Art Museum.

Mark Bradford, Waterfall, 2015. Mixed media.

page 4 of 9

Depicting Kahlo at work and at play, wearing traditional Mexican garb and in the (surprising) guise of a man, the show’s five sections — “Posing,” “Composing,” “Exposing,” “Queering” and “Self-Fashioning” — explore how the artist and others constructed and reconstructed her identity. Kahlo is shown as a toddler, photographed by her father, and on her deathbed. The show includes her earliest artwork and her final two self-portraits.

At a very young age, Kahlo “learned how to strike a pose and perform for the camera,” Ankori says. And, as the exhibition demonstrates, the performance continued throughout the artist’s abbreviated, pain-wracked and trailblazing life.

A groundbreaking museum is saved

The Rose’s anniversary celebration marks a triumphal turn in a storied and sometimes tumultuous history. Rooted in the now-legendary collecting exploits of the museum’s founding director, Sam Hunter, and a series of cutting-edge exhibitions, this history also includes the infamous near-death experience of 2009.

In January of that year, responding to the Great Recession and the university’s shrinking endowment, then-president Jehuda Reinharz announced a plan, approved by the university’s Board of Trustees, to close the museum and sell its assets.

Some of the most valuable pieces in the Rose’s collection derived from a $50,000 gift made to the museum in 1962 by Leon Mnuchin and his wife, Harriet Gevirtz-Mnuchin. Spending no more than $5,000 on a single artwork, Hunter — who had been an art critic, art history professor, and museum curator and director — visited artists’ studios, and secured Pop Art masterpieces by Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, Roy Lichtenstein, Jasper Johns and others.

Charles Mayer Photography

Robert Rauschenberg, “Second Time Painting,” 1961. Oil and assemblage on canvas.

page 5 of 9

The art Hunter purchased is now worth millions. “He totally knew what he was doing,” says Kimerly Rorschach ’78, retired director of the Seattle Art Museum and a member of the Rose board of advisers. “He was very well-connected to the New York art world at the time.”

Hunter collected a few female artists — Marisol’s wooden sculpture Ruth (1961) and Yayoi Kusama’s Blue Coat (1965) are on display in “re: collections.” Later Rose directors and curators would help diversify the collection in terms of artists’ gender, race, ethnicity and sexual orientation.

Over the years, the Rose became known for its groundbreaking exhibitions. Rubin cites “Vision and Television” in 1970, widely regarded as the first show to focus on video art, and “More Than Minimal: Feminism and Abstraction in the ’70s,” mounted in 1996. The Rose also has given important contemporary artists their first solo museum shows, notably hosting Russia-born sculptor Louise Nevelson’s retrospective in 1967.

For a small university museum, the Rose has enjoyed a high profile in the world of modern and contemporary art. Not surprisingly, the proposed 2009 closure triggered widespread dismay among the Rose’s leadership, the museum’s supporters and the art world at large. New York Times art critic Roberta Smith called the vote to auction off the Rose’s collection “an act of breathtaking stealth and presumption.”

Rorschach, who directed the University of Chicago and Duke University art museums before assuming the Seattle post, developed a close connection to the Rose as an undergraduate. “The Rose really showed me how exciting it would be to work in a museum,” she says. “It made me what I am, what I became in life.” When she learned of the museum’s possible demise, she says, “I had a visceral reaction. I was so upset I picked up the phone and called the president’s office.” Her call was not returned. Behind the scenes, she made the case that shutting down the Rose constituted “mission suicide for the university, a big misstep, a panic move.”

© Radcliffe Bailey. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery. Photo by Mel Taing, 2021. Courtesy of the Rose Art Museum.

Radcliffe Bailey, Storm at Sea, 2007. Piano keys, African sculpture, model boat, paper, acrylic, glitter, gold leaf.

page 6 of 9

Three museum board members and benefactors (later joined by a fourth) filed a lawsuit to halt the closure. A university-appointed committee recommended in September 2009 that the Rose remain an art museum open to the public and that it become better integrated into the university’s academic mission. In summer 2011, with a new university president, Frederick M. Lawrence, at the helm, Brandeis reached an amicable settlement in the lawsuit, ensuring the Rose’s future.

This future now includes a renewed commitment to promoting racial and social justice. In an appendix to the working draft of the university’s Anti-Racism Plan, the Rose describes its vision in these terms:

The Rose Art Museum is working actively and intentionally to transform the museum into an anti-racist institution and a nexus of art, communities and justice. Pursuing an uncharted path, we are committed to interrogating our practices and premises, uncovering and critically examining our blind spots and shortcomings, and working to dismantle the colonialist foundations and exploitative legacies of the Western museum. We are planning and implementing new inclusive and equitable ways of being and doing museum work.

“The idea of social justice intertwined with art and art making has long been part of the Rose’s mission,” says Rubin, who has been at the museum since 2013. “The Rose took shape in the way it did in large part because of the community and the environment of Brandeis University, founded as a radical institution, a haven for radical thinkers and a center of student activism. The Rose couldn’t help but be influenced by that, and that’s something we want to celebrate.”

Ankori says, “What will transformational change look like? I don’t want to produce rhetoric. The Rose team and I are immersed in profound, ongoing work that is self-reflective, and it is a difficult and slow process. We ask, ‘What are our blind spots? How are we doing museum work, and what can we do better? Are we welcoming to all communities? How do we work with our neighbors in Waltham so they feel the Rose is their museum? How can we integrate the museum into the social, cultural and academic fabric of Brandeis, the Greater Boston area and beyond?’”

© Estate of Beauford Delaney. Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, New York, New York.

Beauford Delaney, “Abstraction (Greene Street)," 1950. Oil on canvas.

page 7 of 9

Neither straightforward nor well-traveled

Both Ankori’s scholarship and her long association with the Rose have prepared her for the challenges ahead. The author of numerous publications on Frida Kahlo, Israeli art, Palestinian art, feminism and art, and disability studies, she has a deep understanding of marginalized artists, not just the well-known European and U.S. male artists. “Looking at art through critical theoretical lenses over many years of research, teaching, curating and publishing directly impacted the curatorial stance employed in ‘re: collections,’” she says.

A former chair of the art history department at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Ankori says her admiration of the Rose helped lure her to Brandeis in 2010. She has since curated three exhibitions, and served as faculty curator and a member of the museum’s collections committee and board of advisers. She became the museum’s interim director in July 2020 and its director six months later.

On her first day on the job, Ankori asked the university’s chief diversity officer to conduct a workshop for her staff. Staff members now meet weekly to consider diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility (DEIA) issues. Anthony DiPietro, the museum’s associate director for administration and operations, and newly designated DEIA partner, moderates the discussions.

“Museums are very hierarchical, as is academia,” Ankori says. “I’m trying to work with my team to formulate a new model where every single staff member has a voice.”

Inspired by a group called WAGE (Working Artists and the Greater Economy), the Rose has committed to fair pay for artists and others who work with and for the museum. While protecting staff jobs, she has sought out curatorial, design, administrative and board expertise from diverse voices. One new board member, Archy LaSalle, a fine-art photographer and educator, is the founder of the group Where Are All the Black People At, which aims to increase the representation of Black artists in museum collections.

Charles Mayer Photography

Ellsworth Kelly, “Blue White,” 1962. Oil on canvas.

page 8 of 9

Ankori says she envisions the Rose as a pipeline for young talent, explaining that she’s followed Hill’s “brilliant” work since the guest curator was a PhD student at UCLA. Ankori invited Hill to co-curate “re: collections” because she knew Hill’s expertise in Africa and the African diaspora “would bring new perspectives and innovative interpretations of the museum’s holdings.” (Hill has pointed out, for instance, that the chains in Melvin Edwards’ sculpture series Lynch Fragments refer not just to American slavery and racial murders, but to African masks.) Ankori and Hill are co-curating another Rose exhibition, titled “My Mechanical Sketchbook: Barkley L. Hendricks and Photography,” which will replace the Kahlo show in February.

Hill, now an assistant professor of art history at Southern Methodist University, sees the path to becoming an anti-racist institution as neither straightforward nor well-traveled. “To me, it always feels like such tiny baby steps,” she says. “But it’s important to make those tiny baby steps.”

Recently, the Rose partnered with Brandeis’ Student Support Services program for first-generation and low-income students. Participating students chose to focus on three sculptures in the anniversary show: Ruth; Storm at Sea; and Treasure Chest (New Bedford Harbor), a 1998 piece by Mark Dion. “The students studied and experienced the works, and then wrote movingly about the art and its connection to their personal journey,” Ankori says. “In a closing ceremony, they became incredible educators, leading deep and meaningful discussions.”

The Rose’s programs coordinator, Elizabeth Moy, mentored the museum’s first teen intern from Waltham this summer. Other initiatives have included hiring students from underrepresented groups as interns and establishing a Rose campus council, composed of students, staff and faculty, “to help the museum become more welcoming, better integrated into the Brandeis curriculum and just better overall,” says Ankori.

In assessing the Rose collection, Ankori says she and her staff ask, “Who determines what is collected? What isn’t being collected? Where are the gaps?”

Image courtesy of the artist and 47 Canal, New York.

Elle Pérez, “Nicole,” 2018. Archival pigment print on paper.

page 9 of 9

Ankori applauds her predecessors’ strides toward inclusiveness — Christopher Bedford’s focus on African American abstract artists, Luis Croquer’s interest in transgender and Latinx artists. “I want to further expand and open up our collecting practices, and to reflect the global aspects of contemporary art,” she says.

“It’s not that I don’t want to show our iconic pieces. I absolutely do, and ‘re: collections’ highlights many of them,” Ankori stresses. “But I also want to display lesser-known visual voices that narrate overlooked stories that reflect different experiences and hail from diverse parts of the world. Finding artworks in the Rose collection that have never been shown and exhibiting them in conversation with really well-known works can shift traditional art-historical narratives, spark new ideas and produce new knowledge. This is one of the important missions of a university museum.”

Hill describes the curators’ task this way: “We’re taking a text that’s already written, and we’re cutting it up into little pieces, and putting it back together, and saying, ‘OK, how many other stories can we tell?’”

Julia M. Klein is a cultural reporter and critic in Philadelphia. Follow her on Twitter.