Perspective

The Welfare State Is Nothing New

From its very beginnings, the United States has sought to provide for its needy.

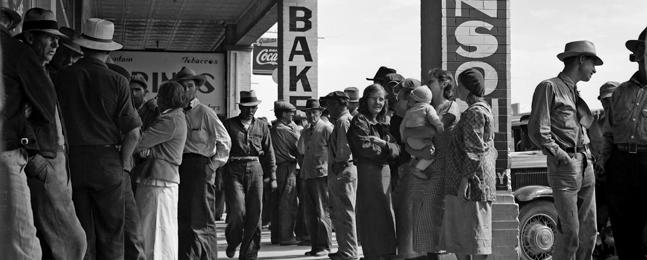

Dorothea Lange, Courtesy Library of Congress

People waiting for government-assistance checks in Calipatria, California, in 1937.

by Gabriel Loiacono, PhD’08

“This is my grandson. He’s getting a PhD at Brandywine.”

“Brandeis,” I corrected, smiling throughout my grandfather’s introduction of me to yet another of his many friends.

A stroke and Parkinson’s prevented Carl Thompson’s mouth from keeping up with his still-sharp mind. He actually knew quite a bit about Brandeis. He valued education and respected Brandeis’ reputation, and understood his friends would, too. That’s why he led with my Brandeis pedigree when I met him and his friends over nonalcoholic beers at lunch.

My grandfather earned a high school diploma while he was in the U.S. Marine Corps after growing up in a hard-working Irish American family. From a young age, he had labored on other people’s farms and in factories in small Connecticut towns. Long retired from the printing press industry by the time I came to Brandeis, he was still a voracious reader of newspapers.

Along with education, he also valued the welfare state, though I never heard him call it that. Old enough to remember what poorhouses were like — his friend’s dad was a poorhouse keeper — he saw the massive changes brought about by Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. I once asked him to show me where the poorhouse had been in his hometown. As we drove past the old farm, I asked what kind of people lived there. “A lot of old guys,” he responded.

Years later, I’ve learned that is pretty close to how history scholars would answer that question, too, though they would use many more words.

I study the poorhouses and poor relief of early-19th-century America, a period that predates my grandfather’s earliest recollections by about 100 years. In “How Welfare Worked in the Early United States: Five Microhistories,” a book published this year, I tell true stories about poor relief by looking at the lives of people who doled it out or received it.

Many readers are surprised to learn that what we now call “welfare” existed even during the time of George Washington. In fact, it probably loomed larger in most Americans’ lives then than it does now. Up until about 1830, the biggest chunk of taxpayer dollars went to paying for welfare.

Understanding how early Americans cared for the neediest among them is an important source of information for us today. Although I am not expert in the current constellation of social-assistance programs, I can offer some insights into the approaches we might want to avoid or emulate.

For instance, through the late 19th century, restrictive “poor laws” governed where many Americans could — or could not — move. Though enforcement varied from state to state, municipal officials who served as overseers of the poor were required to provide as much help as locals needed, which meant that preventing out-of-towners from moving in was sometimes necessary to keep poor-relief expenditures from ballooning. We’d be shocked if a local official barred us from renting a house in Waltham simply because we were born in Newton, Massachusetts, or New York City. But in the early U.S., municipal officials in several states could do just that to keep their relief costs down.

Moreover, once overseers of the poor were legally obliged to provide for you, they assumed great power over you. They might force you to live in a neighbor’s house, or a poorhouse. Almost automatically, they separated children from poor parents or single mothers. In New England, officials wielded their powers in an explicitly discriminatory way: targeting African American and Indigenous families, above all others, for banishment or family separation.

At the same time, there are other features of early-American poor relief we might want to revisit. It was an intensely local system, remunerating neighbors who cared for their neighbors. Taxpayers likely knew the people they were helping to support. This is one reason poor relief had so much buy-in. Grocers, homeowners with a spare bed, women with the time and skill to nurse a patient, and day laborers who could split firewood could all earn tax dollars for helping their neediest neighbors.

Something else we might admire is that, in theory, everyone had a town that would take care of them in their time of need. Poor laws acted as a promise that no one would die for lack of housing, food, clothes or heat, or even doctor’s visits, medicine or full-time health care.

My grandfather would have been the first to say that some things have changed dramatically for the better since the days of poorhouses. Nationalization of many social-assistance and -insurance programs makes it possible for “old guys” to live at home, for mothers to stay with their children and for citizens to carry benefits with them from one town to the next.

Yet, as we debate the future of health care and welfare, we should remember that early Americans thought poor relief was a necessary part of society and a necessary part of government. Early Americans were willing to give a lot to help their fellow human beings. And this was a choice that engendered little to no political controversy.

Gabriel Loiacono is an associate professor of history at the University of Wisconsin Oshkosh and the author of “How Welfare Worked in the Early United States: Five Microhistories” (Oxford University Press, 2021).